Why Systems Biologists Now Assume Life Is Optimally Designed

- Brian Miller

In my last two articles (here, here), I described the revolution occurring in systems biology where practitioners have replaced evolutionary presuppositions with design-based assumptions such as the central role of teleology. Now, I will survey how biologists have increasingly abandoned the belief that poor design in life is pervasive. Instead, they commonly assume that biological structures and systems are highly optimized.

Expectation of Poor Design

The underlying logic of the standard evolutionary model predicts that deficient design and nonfunctional remnants of organisms’ evolutionary past should litter the biosphere. The reason is well summarized in Wikipedia’s article “Argument from Poor Design”:

“Poor design” is consistent with the predictions of the scientific theory of evolution by means of natural selection. This predicts that features that were evolved for certain uses, are then reused or co-opted for different uses, or abandoned altogether; and that suboptimal state is due to the inability of the hereditary mechanism to eliminate the particular vestiges of the evolutionary process.

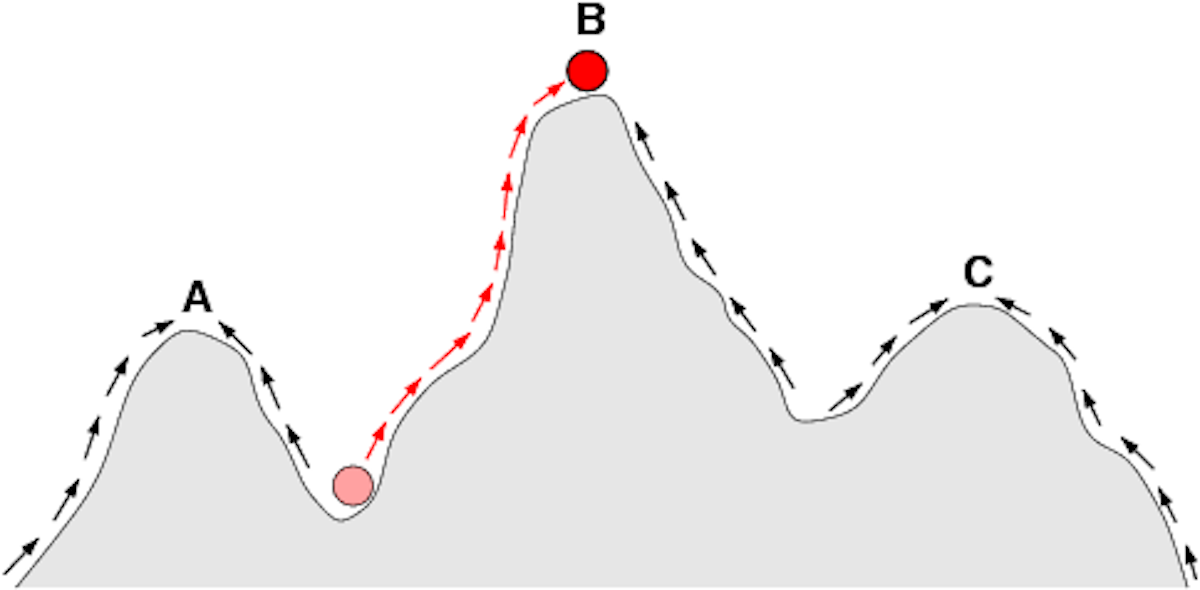

In fitness landscape terms, natural selection will always push “up the hill”, but a species cannot normally get from a lower peak to a higher peak without first going through a valley.

The expectation of poor design is not simply a subjective conclusion based on intuition, but it has been rigorously demonstrated in computational models. One such model created by Snoke, Cox, and Petcher elucidated why evolutionary processes that allow for increases in complexity must generate large quantities of junk DNA and nonfunctional elements. The details of their model are complex, but the underlying logic is straightforward.

For complex innovations to emerge, organisms must allow nonfunctional DNA to appear and persist in the population until a functional sequence arises. Such additions to the genome could occur through a gene duplicating and then repeatedly mutating. Junk DNA would inevitably accumulate to encompass a significant percentage of the genome. This requirement is why biologists once assumed that junk DNA comprised as much as 97 percent of the human genome.

Similarly, the origin of complex structures (e.g., molecular machines) requires countless trial-and-error arrangements of molecules or tissues until something advantageous appears. Most of the trials would be either nonfunctional or inefficient. Consequently, only a minority of biological structures and systems should appear highly optimized.

Central Argument Against Design

The most apparent difference in predictions between intelligent design and undirected evolution is the extent to which life displays suboptimal/nonfunctional versus optimal design. Philosopher Philip Kitcher emphasized this point in his book Living with Darwin: Evolution, Design, and the Future of Faith. He appealed to examples of what he believed were clumsy, incompetent designs as his primary argument for dismissing intelligent design:

If you were a talented engineer designing a whale from scratch, you probably wouldn’t think of equipping it with a rudimentary pelvis. … If you were designing a human body, you could surely improve on the knee. And if you were designing the genomes of organisms, you would certainly not fill them up with junk.

In a similar vein, biologist Nathan Lents argued in his book Human Errors: A Panorama of Our Glitches, from Pointless Bones to Broken Genes that the “bungling” design seen throughout the human body demonstrates that we are not the product of an intelligent designer but of an undirected evolutionary process:

The third category features those human defects that are due to nothing more than the limits of evolution. All species are stuck with the bodies that they have and they can advance only through the tiniest changes, which occur randomly and rarely. We inherited structures that are horrendously inefficient but impossible to change.

This is why our throats convey both food and air through the same tiny space and why our ankles have seven pointless bones sloshing around. Fixing either of those poor designs would require much more than one-at-a-time mutations could ever accomplish. To suppose that these living things were separately created is to view the creative agent as whimsical, bungling, a mediocre engineer, an unintelligent designer.

P. XI-XII

Changing Perspectives

Yet, most of the examples of allegedly poor design cited by Kitcher, Lents, and other skeptics have been overturned (here, here, here, here). The remaining ones typically represent degradations of once optimal designs or appeals to the imperfection-of-the-gaps fallacy.

Purported examples of poor design usually represent opinions resulting from armchair critics’ limited understanding of the technical literature and their lack of training in engineering. For instance, in direct contradiction to Kitcher’s and Lents’s assertions, engineers commonly reuse design motifs in new ways, just as seen with the whale pelvis. And medical professionals and engineers have demonstrated how the human knee and ankle are optimally and exquisitely designed (here, here, here, here). Engineers have even looked to these structures for inspiration in designing artificial limbs (here,here).

Moreover, most of the human genome is now known to be functional thanks to the ENCODE project. The devastating ramifications of this revelation for evolutionary theory have not gone entirely unnoticed. Biochemist Dan Graur bluntly stated the following:

If the human genome is indeed devoid of junk DNA as implied by the ENCODE project, then a long, undirected evolutionary process cannot explain the human genome. If, on the other hand, organisms are designed, then all DNA, or as much as possible, is expected to exhibit function. If ENCODE is right, then evolution is wrong.

“Underlying Optimality Principles”

Of equal significance, systems biologists now recognize that assuming optimal design leads to the most productive research. For instance, Nikolaos Tsiantis, Eva Balsa-Canto, and Julio R. Banga developed a model for studying biological systems based on identifying “underlying optimality principles.” And in their 2018 Bioinformatics article, they surveyed leading researchers who also demonstrated the predictive power of assuming optimality:

Sutherland (2005) claims that these optimality principles allow biology to move from merely explaining patterns or mechanisms to being able to make predictions from first principles. Bialek (2017) makes the important point that optimality hypotheses should not be adopted because of esthetic reasons, but as an approach that can be directly tested through quantitative experiments. Mathematical optimization could therefore be regarded as a fundamental research tool in bioinformatics and computational systems biology.

Other investigators have even shown that biological systems such as DNA replication and translation, embryological development, and sensory processes operate at efficiencies close to the limits of what is physically possible. Human engineering pales in comparison to such achievements.

The vast preponderance of the evidence matches the design-based prediction of optimality. And it directly contradicts a central prediction of any theory of undirected evolution. Will this evidence convince such critics as Kitcher and Lents to rethink their views? Most likely not since their faith in scientific materialism is founded not on empirical evidence but on their philosophical beliefs. Fortunately, many biologists have allowed the evidence to point them in the correct direction despite social pressures to maintain the status quo. These scientists will lead biology through the next great scientific revolution that has just

No comments:

Post a Comment