<iframe width="853" height="480" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/A6Q72R1aYwA" title="YouTube video player" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture" allowfullscreen></iframe>

the bible,truth,God's kingdom,JEHOVAH God,New World,JEHOVAH Witnesses,God's church,Christianity,apologetics,spirituality.

Saturday, 23 April 2022

On Russia's "Cosa Nostra"

Saving junk DNA?

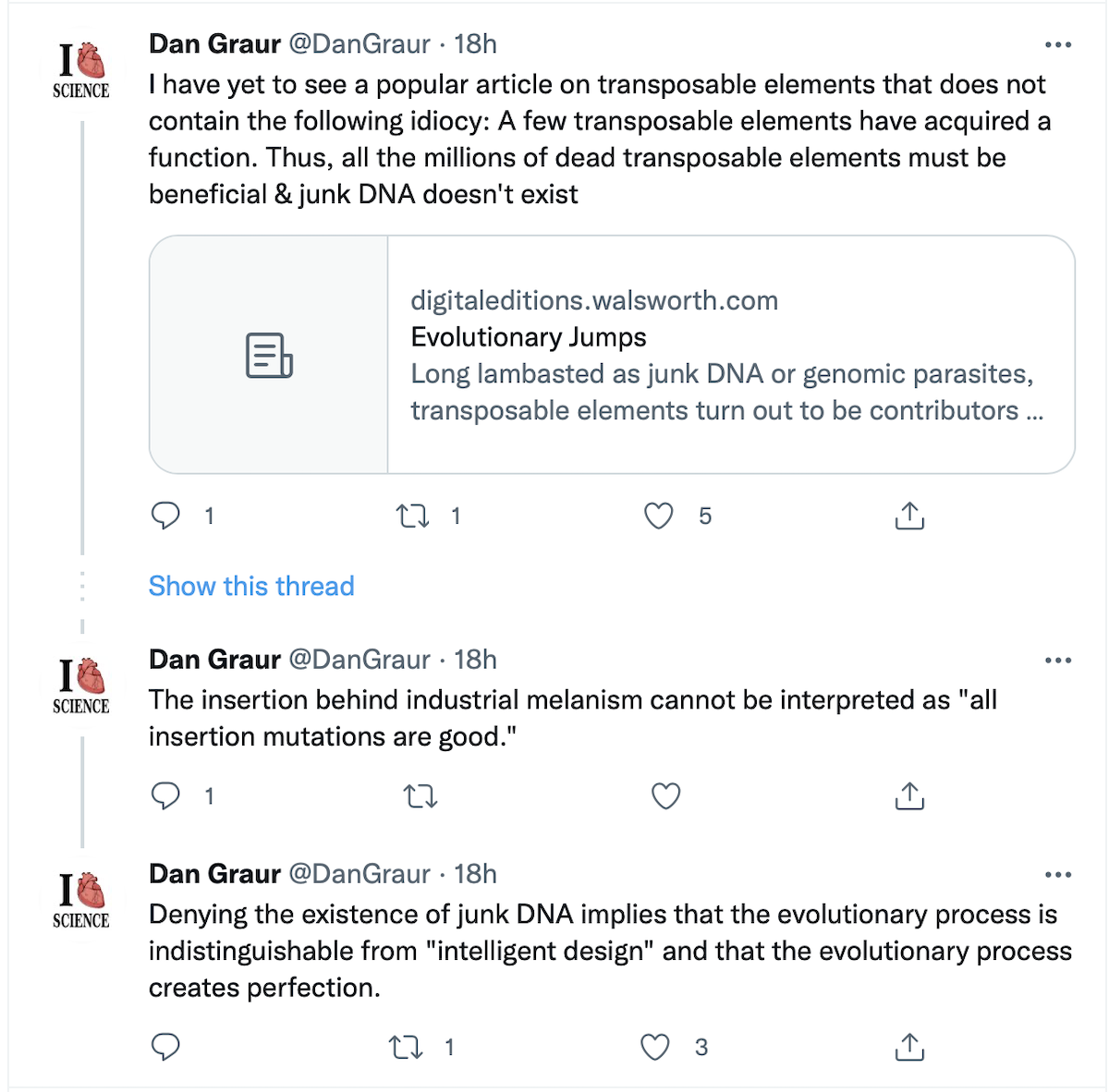

Dan Graur: The Core Rationale for Claiming “Junk DNA”

See the last entry in this Twitter thread (below), and then our follow-up comments under the screen capture. Dan Graur is a University of Houston biologist and prominent junk DNA advocate. The link to the article in The Scientist that he is grumbling about is included at the very end of this post.

So What’s Wrong with Graur’s Argument?

First, it is unlikely that the growing number of biologists looking for possible functions in so-called “junk DNA” are ID proponents (although a few might be).

Consider this syllogism, however:

- Evolutionary processes lack foresight.

- Processes without foresight create novel functions only infrequently, more often causing non-functionality.

- “Junk DNA” appears to be non-functional.

- Therefore, since evolution is true, it is pointless to look for functions in apparently functionless (“junk”) DNA; what appears to lack function, truly does lack function.

Here’s the Problem

Premises (1) and (2) could be true, as doubtless most biologists would agree, yet (3) does not follow from either premise, and refers in any case only to an appearance, exactly the sort of superficial impression calling for further analysis. Moreover, (4) is a counsel of despair — a GENUINE science-stopper. Since “only infrequently” in premise (2) is defined entirely by the sample size, not by evolutionary theory itself, “no function” claims are empirically unsupportable, resting wholly on negative evidence.

Graur’s argument also affirms the consequent, as tendentious arguments often do. Just take a look at premises (2) and (3) and their logical relation.

That explains why many researchers, who are fully on board with evolution, nonetheless ignore Graur’s advice. They decline to kiss the no-function wall, as Paul Nelson put it back in 2010:

Why Kissing the Wall Is the Worst Possible Heuristic for Biological Discovery

In biology, the claim “structure x has no function” can only topple in one direction, namely, towards the discovery of functions. “No function” represents a brick wall of infinite extent, from which one can only fall backwards, into the waiting arms of a function one didn’t see, or overlooked.

Because one was kissing the wall, so to speak.

Here is the article that got under Graur’s skin: “Evolutionary Jumps,” by Christie Wilcox.

And speaking of election meddling.

<iframe width="784" height="441" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/f9Q19QJpJ4s" title="YouTube video player" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture" allowfullscreen></iframe>

Don't give peace a chance?

<iframe width="784" height="441" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/4IbOUqWbumE" title="YouTube video player" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture" allowfullscreen></iframe>

Another exposition on engineerless engineering.

Darwinists Seek to Explain the Eye’s Engineering Perfection

Yesterday we looked at a paper by Tom Baden and Dan-Eric Nilsson in Current Biology debunking the old canard that the human eye is a bad design because it is wired backwards. We saw them turn the tables and show that, in terms of performance, the inverted retina is actually as good or better than the everted retina. Vertebrate eyes “come close to perfect,” they said. Ask the eagles with “the most acute vision of any animal,” which would include cephalopods with their allegedly more logical arrangement. Eagles win! Squids lose! Baden and Nilsson looked at eyes from an “engineer’s perspective” and shared good reasons for the inverted arrangement. They even spoke of design seven times; “the inverted retinal design is a blessing,” they argued.

And yet they maintain that eyes evolved by blind, unguided natural processes. How can they believe that? In this follow-up, we look at the strategies they use to maintain the Darwinian narrative despite the evidence.

Personification

First, they turn evolution into an engineer. Personification is a common ploy by Darwinists. Richard Dawkins envisioned a “blind watchmaker” replacing Paley’s artificer. Darwin even gave natural selection a gender:

Natural selection acts only by taking advantage of slight, successive variations. She can never take a great and sudden leap, but must advance by short and sure, though slow steps.

Evolutionists speak freely of natural selection as a “tinkerer” cobbling together whatever odd parts are handy so that a solution, however, awkward, comes to satisfy a need brought on by “selection pressure.” The resulting structures give the illusion of design but are not the work of a rational agent. Neil Thomas calls such stories “agentless acts” by which engineered structures arise by “pure automatism or magical instrumentality quite outside common experience or observability.” Evolutionists need no magician; the rabbit emerges out of the hat spontaneously, as if an invisible hand pulled on its ears. Watch how Baden and Nilsson personify evolution and turn it into a Blind Tweaker and Opportunist:

So, in general, the apparent challenges with an inverted retina seem to have been practically abolished by persistent evolutionary tweaking. In addition, opportunities that come with the inverted retina have been efficiently seized. In terms of performance, vertebrate eyes come close to perfect. [Emphasis added.]

Visualization

A second tactic Baden and Nilsson use is visualization. Figure 3 in their article shows three stages of a possible evolutionary path from a primitive photoreceptor to a “high quality spatial vision” with “usable space” between the lens and retina. “This space could be usefully filled by the addition of neurons that locally pre-process the image picked up by the photoreceptors,” the caption reads. Well, then, what personified tinkerer would not take advantage of such prime real estate? Give the Blind Tweaker room to homestead and you will shortly find him (or her) setting up shop. What’s missing in the visuals are giant leaps over engineered systems in the gaps, and an account of how they all become coordinated to make vision work.

Inevitability

Another tactic used by Baden and Nilsson is the notion of inevitability. Evolution was forced to take the path it did. Evolution had no choice, they imply, because the first time a layer of light-sensitive cells began to invaginate into a cup shape, the path forward was set in concrete.

The specific reason for our own retinal orientation is the way the nervous system was internalised by invagination of the dorsal epidermis into a neural tube in our pre-chordate ancestors. The epithelial orientation in the neural tube is truly inside out. The vertebrate eye cup develops from a frontal (brain) part of the neural tube, where the receptive parts of any sensory cells naturally project inwards into the lumen of the neural tube (the original outside). In contrast, the eyes of octopus and other cephalopods develop from cups formed in the skin, and the original epithelial outside keeps its orientation.

This tactic gives a Darwinist the flexibility to use the same theory to explain opposite things. Evolution is so rigid it must follow the path the ancestor took, but so malleable that all subsequent engineering can be optimized to perfection. Surely, though, if natural selection has the magical powers the Darwinists ascribe to it, it could have ditched ancestral traditions and remodeled the eye cup. Isn’t that how all innovations begin in the theory?

Airy Nothings

The sneakiest tactic used by the authors is what Neil Thomas described as “notional terms.” These are “airy nothings” and “empty signifiers” that gloss over difficulties by replacing evidence with factoids. A factoid, Thomas says, is “a contention without empirical foundation or any locatable referent in the tangible world but one nevertheless held to be true by the person who proposes it” (italics in original). To use this tactic, just assume that your notion is true. Complex things evolved. They originated. They emerged. They arose. They started. They came. They developed. They improved.

Bipolar cells emerged, slotting in between the cones and the ganglion cells to provide a second synaptic layer right in the sensory periphery. Further finesse came through the addition of horizontal and amacrine cells. The result is a structurally highly stereotyped sheet of neuronal tissue present in all extant vertebrates….

Notional terms like this, that assume what need to be proved, can slip through unnoticed unless one is on guard for them. The following contains two of them, while distracting readers with the ID-friendly argument that the eye is not flawed.

Arguments for a basically flawed orientation of the vertebrate retina are built around an eye that we encounter in a grossly enlarged state compared to its humbler origins. We are now more than 500 million years down the road from where vertebrate vision started in the early Cambrian.

When the readers weren’t paying attention, they were being told that the eye had humble origins in the early Cambrian. A truer statement would have read, “Arguments for a basically flawed orientation of the vertebrate retina are built around the assumption of Darwinian evolution.”

Consensus

Baden and Nilsson might counter that they don’t need to give any details about how evolution achieved engineering perfection, because the scientific community has already reached a consensus that Darwinian evolution explains everything in biology, so they can just take it for granted. This is a form of argument from authority, but worse in this instance. As shown in the previous post, the strongest case for eye evolution — so strong that Richard Dawkins celebrated it publicly — was the 1994 graphic that Jonathan Wells and David Berlinski exposed, and Nilsson was one of the perpetrators! To take that for granted would be like drawing a picture of a unicorn in 1994 and then using that drawing as evidence for unicorns in 2022. Evolutionists leaped onto that 1994 article because nothing better had shown up since Darwin got cold shudders considering this “organ of extreme perfection,” the eye.

The Power of Master Narratives

A doctorate in a relatively rare field of expertise called the Rhetoric of Science is held by Thomas Woodward, author of Doubts About Darwin (2003). In that book he examines the role of “fantasy themes” (which he prefers to call “projection themes”) in the history of the Darwin versus Design debate. One of these is the “progress narrative” that the universe is on a continuous path toward higher complexity (p. 52). These projection themes — not empirical data — were of paramount importance in the wide acceptance of evolution when the Victorian atmosphere was fragrant with feelings of progress. Darwin and his successors had a simple, compelling story that was part “factual-empirical narrative” and part “semi-imaginative narrative” (p. 22).

To understand how Darwinians continue to maintain what appears to ID advocates as cognitive dissonance, i.e., that nature is exquisitely engineered but emerged by blind processes, observers need to be cognizant of the projection themes and rhetorical tactics Darwinians use to forestall a Design Revolution. The ones used by Baden and Nilsson cannot be conquered merely by appeals to empirical facts. They need to be exposed as the ploys they are and supplanted by better narratives founded on stronger evidence and logic.

Charles Darwin the design advocate?

Charles Darwin’s “Intelligent Design”

I wrote here yesterday about Charles Darwin’s orchid book. Shortly after its publication, reviews of the book began appearing in the British press. Unlike with the Origin, the reviews were overwhelmingly positive. Reviewers were extremely impressed with Darwin’s detailed documentation of the variety of contrivances in orchids. But much to Darwin’s dismay, they did not see this as evidence of natural selection.

An anonymous reviewer in the Annals and Magazine of Natural History wrote in response to Darwin’s contention that nature abhors perpetual self-fertilization:

Apart from this theory and that of ‘natural selection,’ which we cannot think is much advanced by the present volume, we must welcome this work of Mr. Darwin’s as a most important and interesting addition to botanical literature.

Other reviewers went much further. M. J. Berkeley, writing in the London Review, said:

…the whole series of the Bridgewater Treatises will not afford so striking a set of arguments in favour of natural theology as those which he has here displayed.

Marvels of Divine Handiwork

A review by R. Vaughn in the British Quarterly Review opined:

No one acquainted with even the very rudiments of botany will have any difficulty in understanding the book before us, and no one without such acquaintance need hesitate to commence the study of it. For, in the first place, it is full of the marvels of Divine handiwork.

According to the Saturday Review:

By contrivances so wonderful and manifold, that, after reading Mr. Darwin’s enumeration of them, we felt a certain awe steal over the mind, as in the presence of a new revelation of the mysteriousness of creation.

“New and Marvelous Instances of Design”

Even Darwin’s pigeon-fancier friend, William Tegetmeier, noted the existence in the book of “new and marvelous instances of design.” And an anonymous reviewer in the British and Foreign Medico-Chirurgical Review wrote:

To those whose delight it is to dwell upon the manifold instances of intelligent design which everywhere surround us, this book will be a rich storehouse.

Darwin’s “flank movement on the enemy” failed miserably. Unable to make a convincing case for natural selection in his broader species work, he tried instead to stealthily impress the scientific world by appeal to the exquisite variety of fertilization methods among orchids. Darwin impressed the scientific world alright. He showed how difficult it is to understand the variety of living organisms without appeal to design.

His orchid book may well be the most important of all Darwin’s publications. It made a unique contribution to 19th-century natural history — or is that natural theology? I can think of no greater irony than the fact that Charles Darwin, who Richard Dawkins felt made it possible to be an intellectually fulfilled atheist, actually bequeathed to 19th-century natural historians one of the most impressive cases for intelligent design ever made.

JEHOVAH may have known what he was doing after all?

Evolutionists: The Eye Is “Close to Perfect”

Two evolutionists have made a stunning admission: the human eye is not oriented backwards. This collapses a long-standing argument for poor design in the eye. There are good reasons why vertebrate eyes have backward-pointing retinas, they say. In fact, human eyes may outperform the eyes of cephalopods, which have been held up as a smarter example of engineering design.

Our analysis of this major rethink will be divided into two parts. First, we will see why the design of the human eye, with its backward-pointing retina, makes sense. Second, we will see how the authors try to rescue Darwinism from this major rethink. Of special interest to this story is that one of the authors, Dan-Eric Nilsson, made a splash with Suzanne Pelger in 1994 with a graphic of eye evolution showing how a light-sensitive spot could evolve into a vertebrate eye in stages. Richard Dawkins made hay with that story. The episode required a lot of fact-checking to refute, as Jonathan Wells and David Berlinski remember.

Terms and Facts

A couple of terms and facts should be enunciated. Cephalopods (octopuses, squid, and cuttlefish) have everted retinas, with the photoreceptor cells pointing toward the light source. Vertebrates all have inverted retinas, with the photoreceptors pointed away from the light source. Some other invertebrates have either one arrangement or the other. Some animals, like zebrafish larvae, have no vitreous space between the lens and the retina. Humans exemplify most vertebrate arrangements with a fluid-filled vitreous humor between the lens and retina.

The new article by Tom Baden and Dan-Eric Nilsson appeared this month in Current Biology, under the title, “Is Our Retina Really Upside Down?” They do not argue that one form is better than the other, but rather, because of trade-offs owing to size, habitat, and behavior, what works for one animal may not be optimal for another.

But in general, it is not possible to say that either retinal orientation is superior to the other. It is the notions of right way or wrong way that fails. Our retina is not upside down, unless perhaps when we stand on our head.

Criticisms of the “Backward Retina” Disappear

Knowing that many of their evolutionary colleagues have criticized the inverted retina as a bad design, Baden and Nilsson elaborate on the criticism then state their thesis:

From an engineer’s perspective, these problems could be trivially averted if the retina were the other way round, with photoreceptors facing towards the centre of the eye. Accordingly, the human retina appears to be upside down. However, here we argue that things are perhaps not quite so black and white. Ranging from evolutionary history via neuronal economy to behaviour, there are in fact plenty of reasons why an inverted retinal design might be considered advantageous. [Emphasis added.]

For the remainder of the article, with 28 references, they consider advantages of the inverted retina, which humans share with all other vertebrates, and the everted retina shared by most invertebrates, with ample evolutionary storytelling thrown in. Here are specific criticisms of the inverted retina with their responses.

Blind spot. The inverted retina needs a place for bundling the nerves from the photoreceptors into a hole so they can join in the optic nerve to the brain. This so-called blind spot is “not all that bad,” they point out; it only occupies 1% of the visual field in humans and is filled in with data from the other eye. “Moreover, body movements can ensure suitable sampling of visual scenes despite this nuisance,” they say. “After all, when is the last time you have felt inconvenienced by your own blind spots?”

Optically compromised space. Surely the tangles of neural cells in front of the photoreceptors reduce optical quality, don’t they? Not really, say Baden and Nilsson, for several reasons:

Looking out through a layer of neural tissue may seem to be a serious drawback for vertebrate vision. Yet, vertebrates include birds of prey with the most acute vision of any animal, and even in general, vertebrate visual acuity is typically limited by the physics of light, and not by retinal imperfections. Likewise, photoreceptor cell bodies, which in vertebrate eyes are also in the way of the retinal image, do not seem to strongly limit visual acuity. Instead, in several lineages, which include species of fish, reptiles and birds, these cell bodies contain oil droplets that improve colour vision and/or clumps of mitochondria that not only provide energy but also help focus the light onto the photoreceptor outer segments.

They don’t specifically mention the Mueller cells that act as waveguides to the photoreceptors, but surely those are among the “surprising” ways that the “design challenges have been met” in the inverted retina.

Benefits of Inverted Retinas

The inverted retina also provides distinct advantages:

Preprocessing. One thing the everted retina cannot do as well is process the information before it gets to the brain. Baden and Nilsson spend some time discussing why this is so very beneficial.

To fully understand the merits of the inverted design, we need to consider how visual information is best processed. The highly correlated structure of natural light means that the vast majority of light patterns sampled by eyes are redundant. Using retinal processing, vertebrate eyes manage to discard much of this redundancy, which greatly reduces the amount of information that needs to be transmitted to the brain.This saves colossal amounts of energy and keeps the thickness of the optic nerve in check, which in turn aids eye movements.

For example, they say, a blue sky consists of mostly redundant information. The vertebrate eye “truly excels” at concentrating on new and unexpected information, like the shadow of a bird flying against the sky. Neurons that monitor portions of the visual field that have not changed can stay inactive, saving energy. What’s more, the vertebrate eye contains layers of specialized cells that preprocess the information sent to the brain, giving the eye “predictive coding” as reported elsewhere. They touch on that fact here:

The extensive local circuitry within the eye — enabled by two thick and densely interconnected synaptic layers, achieves an amazingly efficient, parallel representation of the visual scene. By the time the signal gets to the ganglion cells that form the optic nerve, spikes are mostly driven by the presence of the unexpected.

Useful space. The inverted retina uses to good advantage the vitreous space for placing the “extensive local circuitry” for the preprocessing cells. Squid eyes, with the photoreceptors smack against the optic lobe, lack that benefit. Here, Baden and Nilsson turn the tables on the “bad design” critics so eloquently one must read it in their own words:

Returning to our central narrative, the intraocular space of vertebrate eyes is an ideal location for such early processing, hinting that the vertebrate retina is in fact cleverly oriented the right way! … Taking larval zebrafish as the best studied example, the somata and axons of their ganglion cells are squished up right against the lens, while on the other end the outer segment of photoreceptors sits neatly inserted into the pigment epithelium that lines the eyeball. Clearly, in these smallest of perfectly functional vertebrate eyes, the inverted retina has allowed efficient use of every cubic micron of intraocular real estate. In contrast, now it is suddenly the cephalopod retina that appears to have an awkward orientation. … For tiny eyes, the everted design wastes extremely valuable space inside the eye whereas the inverted retinal design is a blessing. With this reasoning, cephalopods have an unfortunate retinal orientation and, contrary to the general notion, it is the vertebrate retina that is the right way up.

“Close to Perfect”

As a capstone to their argument, they conclude that “In terms of performance, vertebrate eyes come close to perfect.” This does not mean the poor octopus is the loser in this surprising upset. If scientists knew more about cephalopod eye performance within the animals’ own circumstances, a similar conclusion would probably be justified. “Both the inverted and the everted principles of retinal design have their advantages and their challenges, or shall we say ‘opportunities’.”

Surely with all this engineering and design talk, the authors are

ready to jump the Darwin ship and join the ID community, right? One must

never underestimate the stubbornness and storytelling ability of

evolutionists. Next time we will look at how they explain all this

engineering perfection in Darwinian terms.

Loaded much?

A Thought Experiment

I’d like to propose a thought experiment for you. I will ask three questions and offer three possible answers for each. I would like you, the reader, to consider the answers as objectively as you can, and pick the answer that is correct. It shouldn’t be too hard, right?

Ah, but if your worldview is at stake, what then?

1. A doctor, having found out that I did intelligent design research, asked me if my research indicated something could evolve that I had thought could not, would I publish it?

A. Of course.

B. No.

C. Keep trying until I get the answer I want.

2. A doctor, having found out that I did evolutionary biology research, asked me if my research indicated something could not evolve that I had thought could, would I publish it?

A. Of course.

B. No.

C. Keep trying until I get the answer I want.

Question 1 happened to me. I answered, “Of course.” This is because I am a scientist first, and an intelligent design advocate second. To even ask the question impugned my integrity as a scientist. That was the point of the question, I suppose.

The same doctor would not ask question 2 of an evolutionary biologist. He was already sure evolution was true, so the question would be meaningless for him.

Final question.

3. Why should anyone think it is OK to question the integrity of a scientist (or anyone) because of her views on intelligent design or evolution?

A. Because they are JUST WRONG. And they ought to know it.

B. Because they are just protecting their turf.

C. It’s not OK.

Well?