Should the Name Jehovah Appear in the New Testament?

DOES it matter whether God’s name appears in the Bible? God obviously felt so. His name, as represented by the four Hebrew characters known as the Tetragrammaton, appears almost 7,000 times in the original Hebrew text of what is commonly called the Old Testament. *

Bible scholars acknowledge that God’s personal name appears in the Old Testament, or Hebrew Scriptures. However, many feel that it did not appear in the original Greek manuscripts of the so-called New Testament.

What happens, then, when a writer of the New Testament quotes passages from the Old Testament in which the Tetragrammaton appears? In these instances, most translators use the word “Lord” rather than God’s personal name. The New World Translation of the Holy Scriptures does not follow this common practice. It uses the name Jehovah 237 times in the Christian Greek Scriptures, or New Testament.

What problems do Bible translators face when it comes to deciding whether to use God’s name in the New Testament? What basis is there for using God’s name in this part of the Holy Scriptures? And how does the use of God’s name in the Bible affect you?

A Translation Problem:

The manuscripts of the New Testament that we possess today are not the originals. The original manuscripts written by Matthew, John, Paul, and others were well used, and no doubt they quickly wore out. Hence, copies were made, and when those wore out, further copies were made. Of the thousands of copies of the New Testament in existence today, most were made at least two centuries after the originals were penned. It appears that by that time those copying the manuscripts either replaced the Tetragrammaton with Kuʹri·os or Kyʹri·os, the Greek word for “Lord,” or copied from manuscripts where this had been done. *

Knowing this, a translator must determine whether there is reasonable evidence that the Tetragrammaton did in fact appear in the original Greek manuscripts. Is there any such proof? Consider the following arguments:

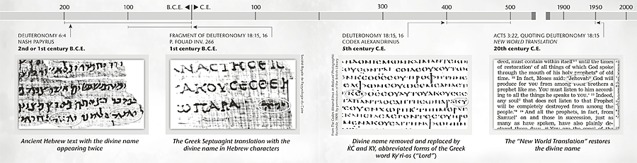

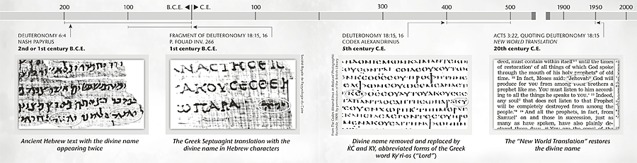

When Jesus quoted the Old Testament or read from it, he used the divine name. (Deuteronomy 6:13, 16; 8:3; Psalm 110:1; Isaiah 61:1, 2; Matthew 4:4, 7, 10; 22:44; Luke 4:16-21) In the days of Jesus and his disciples, the Tetragrammaton appeared in copies of the Hebrew text of what is often called the Old Testament, as it still does today. However, for centuries scholars thought that the Tetragrammaton was absent from manuscripts of the Greek Septuagint translation of the Old Testament, as well as from manuscripts of the New Testament. Then in the mid-20th century, something remarkable came to the attention of scholars—some very old fragments of the Greek Septuagint version that existed in Jesus’ day had been discovered. Those fragments contain the personal name of God, written in Hebrew characters.

Jesus used God’s name and made it known to others. (John 17:6, 11, 12, 26) Jesus plainly stated: “I have come in the name of my Father.” He also stressed that his works were done “in the name of [his] Father.” In fact, Jesus’ own name means “Jehovah Is Salvation.”—John 5:43; 10:25.

The divine name appears in its abbreviated form in the Greek Scriptures. At Revelation 19:1, 3, 4, 6, the divine name is embedded in the expression “Alleluia,” or “Hallelujah.” This expression literally means “Praise Jah, you people!” Jah is a contraction of the name Jehovah.

Early Jewish writings indicate that Jewish Christians used the divine name in their writings. The Tosefta, a written collection of oral laws completed by about 300 C.E., says with regard to Christian writings that were burned on the Sabbath: “The books of the Evangelists and the books of the minim [thought to be Jewish Christians] they do not save from a fire. But they are allowed to burn where they are, . . . they and the references to the Divine Name which are in them.” This same source quotes Rabbi Yosé the Galilean, who lived at the beginning of the second century C.E., as saying that on other days of the week “one cuts out the references to the Divine Name which are in them [the Christian writings] and stores them away, and the rest burns.” Thus, there is strong evidence that the Jews living in the second century C.E. believed that Christians used Jehovah’s name in their writings.

How Have Translators Handled This Issue?

Is the New World Translation the only Bible that restores God’s name when translating the Greek Scriptures? No. Based upon the above evidence, many Bible translators have felt that the divine name should be restored when they translate the New Testament.

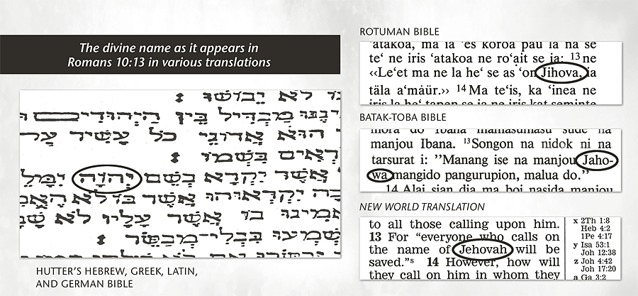

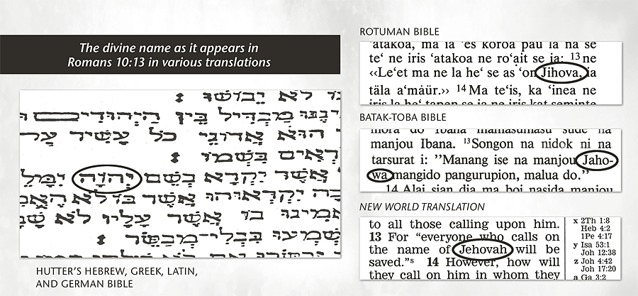

For example, many African, American, Asian, and Pacific-island language versions of the New Testament use the divine name liberally. (See chart on page 21.) Some of these translations have appeared recently, such as the Rotuman Bible (1999), which uses the name Jihova 51 times in 48 verses of the New Testament, and the Batak-Toba version (1989) from Indonesia, which uses the name Jahowa 110 times in the New Testament. The divine name has appeared, too, in French, German, and Spanish translations. For instance, Pablo Besson translated the New Testament into Spanish in the early 20th century. His translation uses Jehová at Jude 14, and nearly 100 footnotes suggest the divine name as a likely rendering.

Below are some examples of English translations that have used God’s name in the New Testament:

A Literal Translation of the New Testament . . . From the Text of the Vatican Manuscript, by Herman Heinfetter (1863)

The Emphatic Diaglott, by Benjamin Wilson (1864)

The Epistles of Paul in Modern English, by George Barker Stevens (1898)

St. Paul’s Epistle to the Romans, by W. G. Rutherford (1900)

The Christian’s Bible—New Testament, by George N. LeFevre (1928)

The New Testament Letters, by J.W.C. Wand, Bishop of London (1946)

Recently, the 2004 edition of the popular New Living Translation made this comment in its preface under the heading “The Rendering of Divine Names”: “We have generally rendered the tetragrammaton (YHWH) consistently as ‘the LORD,’ utilizing a form with small capitals that is common among English translations. This will distinguish it from the name ʹadonai, which we render ‘Lord.’” Then when commenting on the New Testament, it says: “The Greek word kurios is consistently translated ‘Lord,’ except that it is translated ‘LORD’ wherever the New Testament text explicitly quotes from the Old Testament, and the text there has it in small capitals.” (Italics ours.) The translators of this Bible therefore acknowledge that the Tetragrammaton (YHWH) should be represented in these New Testament quotes.

Interestingly, under the heading “Tetragrammaton in the New Testament,” The Anchor Bible Dictionary makes this comment: “There is some evidence that the Tetragrammaton, the Divine Name, Yahweh, appeared in some or all of the O[ld] T[estament] quotations in the N[ew] T[estament] when the NT documents were first penned.” And scholar George Howard says: “Since the Tetragram was still written in the copies of the Greek Bible [the Septuagint] which made up the Scriptures of the early church, it is reasonable to believe that the N[ew] T[estament] writers, when quoting from Scripture, preserved the Tetragram within the biblical text.”

Two Compelling Reasons:

Clearly, then, the New World Translation was not the first Bible to contain the divine name in the New Testament. Like a judge who is called upon to decide a court case for which there are no living eyewitnesses, the New World Bible Translation Committee carefully weighed all the relevant evidence. Based on the facts, they decided to include Jehovah’s name in their translation of the Christian Greek Scriptures. Note two compelling reasons why they did so.

(1) The translators believed that since the Christian Greek Scriptures were an inspired addition to the sacred Hebrew Scriptures, the sudden disappearance of Jehovah’s name from the text seemed inconsistent.

Why is that a reasonable conclusion? About the middle of the first century C.E., the disciple James said to the elders in Jerusalem: “Symeon has related thoroughly how God for the first time turned his attention to the nations to take out of them a people for his name.” (Acts 15:14) Does it sound logical to you that James would make such a statement if nobody in the first century knew or used God’s name?

(2) When copies of the Septuagint were discovered that used the divine name rather than Kyʹri·os (Lord), it became evident to the translators that in Jesus’ day copies of the earlier Scriptures in Greek—and of course those in Hebrew—did contain the divine name.

Apparently, the God-dishonoring tradition of removing the divine name from Greek manuscripts developed only later. What do you think? Would Jesus and his apostles have promoted such a tradition?—Matthew 15:6-9.

Call “on the Name of Jehovah”

Really, the Scriptures themselves act as a conclusive “eyewitness” statement that early Christians did in fact use Jehovah’s name in their writings, especially when they quoted passages from the Old Testament that contain that name. Without a doubt, then, the New World Translation has a clear basis for restoring the divine name, Jehovah, in the Christian Greek Scriptures.

How does this information affect you? Quoting the Hebrew Scriptures, the apostle Paul reminded the Christians in Rome: “Everyone who calls on the name of Jehovah will be saved.” Then he asked: “How will they call on him in whom they have not put faith? How, in turn, will they put faith in him of whom they have not heard?” (Romans 10:13, 14; Joel 2:32) Bible translations that use God’s name when appropriate help you to draw close to God. (James 4:8) Really, what an honor it is for us to be allowed to know and to call upon God’s personal name, Jehovah.

A TRANSLATOR WHO RESPECTED GOD’S NAME

In November 1857, Hiram Bingham II, a 26-year-old missionary, arrived with his wife in the Gilbert Islands (now called Kiribati). The missionary ship on which they had traveled was sponsored by meager donations from American Sunday School children. It had been named the Morning Star by its sponsors to reflect their belief in the coming Millennium.

“Physically, Bingham was not strong,” states Barrie Macdonald in his book Cinderellas of the Empire. “He suffered from frequent bowel ailments, and from chronic throat trouble which affected his ability to speak in public; his eyesight was so weak that he could only spend two or three hours a day reading.”

However, Bingham set his mind to learning the Gilbertese language. This was not an easy task. He started by pointing at objects and asking their names. When he had collected a list of some two thousand words, he paid one of his converts a dollar for every one hundred new words he could add to the list.

Bingham’s perseverance paid off. By the time he had to leave the Gilbert Islands in 1865 because of his deteriorating health, he not only had given the Gilbertese language a written form but had also translated the books of Matthew and John into Gilbertese. When he returned to the islands in 1873, he brought with him the completed translation of the New Testament in Gilbertese. He persevered for a further 17 years and by 1890 completed the translation of the entire Gilbertese Bible.

Bingham’s translation of the Bible is in use in Kiribati to this day. Those reading it will notice that he used Jehovah’s name (Iehova in Gilbertese) thousands of times in the Old Testament as well as over 50 times in the New Testament. Truly, Hiram Bingham was a translator who respected God’s name!