the bible,truth,God's kingdom,JEHOVAH God,New World,JEHOVAH Witnesses,God's church,Christianity,apologetics,spirituality.

Sunday, 26 August 2018

It's design all the way down/up?

From Micro to Macro Scales, Intelligent Design Is in the Details

Evolution News | @DiscoveryCSC

Evolution News | @DiscoveryCSC

From the molecular nanomachines within a tiny cell to the large-scale structure of the universe, design is everywhere to be found. Sometimes the best defense of intelligent design is just to ponder the details. Here are some new illustrations:

Fastest Creature Is a Cell

If you were asked what the fastest creature on earth is, would you guess a cheetah or a peregrine falcon? There’s an even faster critter you would probably never guess. It’s called Spirostomum ambiguum, and it’s just 4mm in size. This protozoan, Live Science says, can shorten its body by 60 percent in just milliseconds. How does it do it? Scientists “have no idea how the single-celled organism can move this fast without the muscle cells of larger creatures,” the article says. “And scientists have no clue how, regardless of how the contraction works, the little critter moves like this without wrecking all of its internal structures.” Saad Bhamla, a researcher at Georgia Tech, wants to find out. And in the process, he will gain design information that can be applied in human engineering:

“As engineers, we like to look at how nature has handled important challenges,” Bhamla said in the release. “We are always thinking about how to make these tiny things that we see zipping around in nature. If we can understand how they work, maybe the information can cross over to fill the gap for small robots that can move fast with little energy use.”

Cells Do “The Wave”

Speaking of speed, most cells have another faster-than-physics trick. When a cell needs to commit hari-kari, it performs an act something like “The Wave” in a baseball stadium. Researchers from Stanford Medicine, investigating programmed cell death or apoptosis, noticed wave-fronts of specialized destroying enzymes, called caspases, spreading throughout the cell faster than diffusion could explain.

Publishing in Science, they hypothesized that “trigger waves” accelerate the process of apoptosis, similar to how a “wave” of moving arms can travel rapidly around a stadium even though each person’s arms are not moving that fast. Another example is how one domino falling can trigger whole chains of dominoes across a gym floor. The mechanism presupposes that the elements, like the dominoes, are already set up in a finely-tuned way to respond appropriately. This may not be the only example of a new design principle. It may explain how the immune system can respond quickly.

“We have all this information on proteins and genes in all sorts of organisms, and we’re trying to understand what the recurring themes are,” Ferrell said. “We show that long-range communication can be accomplished by trigger waves, which depend on things like positive feedback loops, thresholds and spatial coupling mechanisms. These ingredients are present all over the place in biological regulation. Now we want to know where else trigger waves are found.”

The Complicated Ballet

Just organizing a chromosome is a mind-boggling wonder. But what do enzymes do when they need to find a spot on DNA that is constantly in motion? It’s enough to make your head spin. Scientists at the University of Texas at Austin describe it in familiar terms:

Thirumalai suggests thinking of DNA like a book with a recipe for a human, where the piece of information you need is on page 264. Reading the code is easy. But we now understand that the book is moving through time and space. That can make it harder to find page 264.

Yes, and the reader might be at a distant part of the nucleus, too. The challenge is not just academic. Things can go terribly wrong if the reader and book don’t meet up properly. They call it a “complicated ballet” going on.

“Rather than the structure, we chose to look at the dynamics to figure out not only how this huge amount of genetic information is packaged, but also how the various loci move,” said Dave Thirumalai, chair of UT Austin’s chemistry department. “We learned it is not just the genetic code you have to worry about. If the timing of the movement is off, you could end up with functional aberrations.”

Strong Succulent Seeds

The seed coats of some plants, like succulents and grasses, have an odd architecture at the microscopic level. Researchers at the University of New Hampshire, “inspired by elements found in nature,” noticed the wavy-like zigzags in the seed coats and dreamed of applications that need lightweight materials that are strong but not brittle.

The results, published in the journal Advanced Materials, show that the waviness of the mosaic-like tiled structures of the seed coat, called sutural tessellations, plays a key role in determining the mechanical response. Generally, the wavier it is, the more an applied loads [sic] can effectively transit from the soft wavy interface to the hard phase, and therefore both overall strength and toughness can simultaneously be increased.

Researchers say that the design principles described show a promising approach for increasing the mechanical performance of tiled composites of man-made materials. Since the overall mechanical properties of the prototypes could be tuned over a very large range by simply varying the waviness of the mosaic-like structures, they believe it can provide a roadmap for the development of new functionally graded composites that could be used in protection, as well as energy absorption and dissipation.

Small High Flyers

You may remember the episode in Flight about Arctic terns, whose epic flights were tracked by loggers. Another study at Lund University found that even smaller birds fly up to 4,000 meters (over 13,000 feet) high on their migrations to Africa. Only two individuals from two species were tracked, but the researchers believe some of the birds fly even higher on the return flight to Sweden. It’s a mystery how they can adjust their metabolism to such extreme altitude, thin air, low pressure, and low temperature conditions.

Don’t Look for Habitable Planets Here

The centers of galaxies, we learned from The Privileged Planet, are not good places to look for life. Cross off another type of location now: the centers of globular clusters. An astronomer at the University of California, Riverside, studied the large Omega Centauri cluster hopefully, but concluded that “Close encounters between stars in the Milky Way’s largest globular cluster leave little room for habitable planetary systems.” The core of the cluster has mostly red dwarfs, which have their own habitability issues to begin with. Then, Stephen Cane calculated that interactions between the closely-associated stars in the cluster would occur too frequently for comfort. His colleague Sarah Deveny says, “The rate at which stars gravitationally interact with each other would be too high to harbor stable habitable planets.”

Solar Probe Launches

The only habitable planet we know about so far is the earth. Surprisingly, there is still a lot about our own star, the sun, that astronomers do not understand. A new mission is going to fly to the sun to solve some of its mysteries, Space.com reports, but like the old joke says, don’t worry: it’s going at night. Named the Parker Solar Probe after 91-year-old Eugene Parker, who discovered the solar wind in 1958, the spacecraft carries a specially designed heat shield to protect its instruments. The probe will taste some of the material in the solar corona to try to figure out why the corona is much hotter than the surface, the photosphere. See Phys.org to read about some of the mission’s goals.

Speaking of the solar wind, charged particles from the sun would fry any life on the earth were it not for our magnetic field that captures the charged particles and funnels them toward the poles. Word has it that Illustra Media is working on a beautiful new short film about this, explaining how the charged particles collide with the upper atmosphere, producing the beautiful northern and southern lights — giving us an aesthetic natural wonder as well as planetary protection.

Son of the God or son of the apes?

No, We Are Not “Beasts”

Wesley J. Smith

Wesley J. Smith

The New York Times is fond of running “big idea” opinion essays claiming that humans are just another animal in the forest — and, sometimes, that plants are persons too.

This past Sunday’s example involved a writer, Maxim Loskutoff, recounting the time he and his girlfriend were threatened by a grizzly bear while hiking in Montana — a terrifying experience that taught him a lesson. From “The Beast in Me“:

It was a strange epiphany. To be human today is to deny our animal nature, though it’s always there, as the earth remains round beneath our feet even when it feels flat. I had always been an animal, and would always be one, but it wasn’t until I was prey, my own fur standing on end and certain base-level decisions being made in milliseconds (in a part of my mind that often takes 10 minutes to choose toothpaste in the grocery store), that the meat-and-bone reality settled over me. I was smaller and slower than the bear. My claws were no match for hers. And almost every part of me was edible.

Flies, Oysters, and Plankton

Of course we are animals biologically. But so what? Flies, oysters, and most plankton are too. That identifier — in the biological sense — does not have significant import outside of the biological sciences.

But the human/animal dichotomy has a much deeper meaning. Morally, we are a species apart. We are unique, exceptional.

Loskutoff’s life matters more than the threatening grizzly bear’s — which was why a ranger with a very big gun ran up to save the couple, willing to kill the bear if that proved necessary. If the writer was just “prey,” why not let natural selection take its course?

Watch Here for Deep Thinking

And here comes the deep thinking part:

Of course there are aspects of our communal society — caring for the old, the domestication of livestock, the cultivation of crops — that link us to only a few other species, and other aspects, such as the written word, that link us to none as yet discovered, but in no place but our own minds have we truly transcended our animal brethren….As the anthropologist Clifford Geertz famously said, “Man is an animal suspended in webs of significance he himself has spun.”

“Webs of Significance”

That is ridiculous on its face as we are the only species in the known universe that spins “webs of significance.” Only we create meaning and purpose, from which springs moral agency — the knowledge that there is such a thing as right and wrong, and that we should do “right” — another aspect of human exceptionalism. No animal (in the moral sense off the term) does any of that.

Loskutoff’s conclusion is predictable for writing of this genre:

Yet there is something of the experience with the bear that remains inside me, a gift from my moment of pure terror. It’s the knowledge of my animal self. That instinctive, frightened, clear-eyed creature beneath my clothes. And it brought with it the reassuring sense of being part of the natural world, rather than separated from it, as we so often feel ourselves to be. My humanity, one cell in the great, breathing locomotion spreading from sunlight to leaves to root stems to bugs to birds to bears.

I reject that we are merely “one cell in the great, breathing locomotion” of the rest of life on this planet. We are both part of the natural world and self-separated and intentionally apart from it — to the point that we are able to substantially mold nature to meet to our needs and desires.

And with that exceptional moral status comes not only our unique value, but responsibilities to (among others) care properly for the environment and to treat animals humanely — duties that arise simply and merely because we are human.

Animals, in contrast, are amoral. They owe us and each other nothing. After all, that bear would have done nothing “wrong” if she had torn Loskutoff apart for dinner, no matter the agony caused. She would have just been acting like a hungry bear.

That’s a distinction with a world of difference.

The gatekeepers are at it again.

So, Who Is Doing “Pseudoscience”?

Granville Sewell

A new book from MIT Press, Pseudoscience: The Conspiracy Against Science,includes a chapter by Adam Marcus and Ivan Oransky, founders of the website Retraction Watch. In “Pseudoscience, Coming to a Peer-Reviewed Journal Near You,” I found my own name mentioned. They write:

Although one might assume that journals would hold a strong hand when it comes to ridding themselves of bogus papers, that’s not always the case. In 2011, Elsevier’s Applied Mathematics Letters retracted a paper by Granville Sewell of the University of Texas, El Paso, that questioned the validity of the second law of thermodynamics — a curious position for an article in a mathematics journal, but not so curious for someone like Sewell, who apparently favors intelligent design theories over Darwinian natural selection.

Did I really “question the validity of the second law”?

Accepted and Withdrawn

Well, let’s look at the abstract of the accepted but withdrawn-at-the-last-minute Applied Mathematics Letters (AML) article, “A Second Look at the Second Law”:

It is commonly argued that the spectacular increase in order which has occurred on Earth does not violate the second law of thermodynamics because the Earth is an open system, and anything can happen in an open system as long as the entropy increases outside the system compensate the entropy decreases inside the system. However, if we define “X-entropy” to be the entropy associated with any diffusing component X (for example, X might be heat), and, since entropy measures disorder, “X-order” to be the negative of X-entropy, a closer look at the equations for entropy change shows that they not only say that the X-order cannot increase in a closed system, but that they also say that in an open system the X-order cannot increase faster than it is imported though the boundary. Thus the equations for entropy change do not support the illogical “compensation” idea; instead, they illustrate the tautology that “if an increase in order is extremely improbable when a system is closed, it is still extremely improbable when the system is open, unless something is entering which makes it not extremely improbable.” Thus, unless we are willing to argue that the influx of solar energy into the Earth makes the appearance of spaceships, computers and the Internet not extremely improbable, we have to conclude that the second law has in fact been violated here.

In Section 3, I wrote:

The second law of thermodynamics is all about probability; it uses probability at the microscopic level to predict macroscopic change. Carbon distributes itself more and more uniformly in an isolated solid because that is what the laws of probability predict when diffusion alone is operative. Thus the second law predicts that natural (unintelligent) causes will not do macroscopically describable things which are extremely improbable from the microscopic point of view. The reason natural forces can turn a computer or a spaceship into rubble and not vice versa is probability: of all the possible arrangements atoms could take, only a very small percentage could add, subtract, multiply and divide real numbers, or fly astronauts to the moon and back safely…But it is not true that the laws of probability only apply to closed systems: if a system is open, you just have to take into account what is crossing the boundary when deciding what is extremely improbable and what is not.

Then, in my conclusion:

Of course, one can still argue that the spectacular increase in order seen on Earth does not violate the second law because what has happened here is not really extremely improbable… And perhaps it only seems extremely improbable, but really is not, that, under the right conditions, the influx of stellar energy into a planet could cause atoms to rearrange themselves into nuclear power plants and spaceships and digital computers. But one would think that at least this would be considered an open question, and those who argue that it really is extremely improbable, and thus contrary to the basic principle underlying the second law of thermodynamics, would be given a measure of respect, and taken seriously by their colleagues, but we are not.

Even if, as Marcus and Oransky believe, intelligent design were “pseudoscience,” my AML paper was still not pseudoscience. Why? Because it did not mention or promote intelligent design, and it did not question the second law, only the absurd compensation argument, which is always used to avoid the issue of probability when discussing the second law and evolution. But these authors apparently feel that it is pseudoscience to force Darwinists to address the issue of probability when defending their theory against the second law.

A Published Apology

Marcus and Oranski continue:

The article was retracted, according to the notice, “because the Editor-in-Chief subsequently concluded that the content was more philosophical than mathematical and, as such, not appropriate for a technical mathematics journal such as Applied Mathematics Letters.” Beyond the financial remuneration, the real value of the settlement for Sewell was the ability to say — with a straight face — that the paper was not retracted because it was wrong. Such stamps of approval are, in fact, why some of those who engage in pseudoscience want their work to appear in peer-reviewed journals.

Well, whether the article was appropriate for AML or not is debatable, but it was reviewed and accepted, then withdrawn at the last minute, as reported here. And since Elsevier’s guidelines state that a paper can only be withdrawn after acceptance because of major flaws or misconduct, yes, I wanted people to know that Elsevier did not follow its own guidelines, and that the paper was not retracted because major flaws were found, and that is exactly what the published apology acknowledged. Marcus and Oranski omit the first part of the sentence they quote from the apology, which states that the article was withdrawn “not because of any errors or technical problems found by the reviewers or editors.”

They conclude:

And it means that the gatekeepers of science — peer reviewers, journal editors, and publishers — need always be vigilant for the sort of “not even wrong” work that pseudoscience has to offer. Online availability of scholarly literature means that more such papers come to the attention of readers, and there’s no question there are more lurking. Be vigilant. Be very, very vigilant.

In a peer-reviewed 2017 Physics Essays paper, “On ‘Compensating’ Entropy Decreases,” I again criticized the widely used compensation argument, and again I did not question the validity of the second law or explicitly promote intelligent design. Here were my conclusions in that paper:

If Darwin was right, then evolution does not violate the second law because, thanks to natural selection of random mutations, and to the influx of stellar energy, it is not really impossibly improbable that advanced civilizations could spontaneously develop on barren, Earth-like planets. Getting rid of the compensation argument would not change that; what it might change is, maybe science journals and physics texts will no longer say, sure, evolution is astronomically improbable, but there is no conflict with the second law because the Earth is an open system, and things are happening elsewhere which, if reversed, would be even more improbable.

An Unfair Characterization?

And if you think this characterization of the compensation argument is unfair, read the second page (71) of the Physics Essays article and you will see that the American Journal of Physics articles cited there are very explicit in making exactly the argument that evolution is extremely improbable but there is no conflict with the second law because the Earth is an open system and things are happening outside which, if reversed, would be even more improbable. As I point out there, one can make exactly the same argument to say that a tornado running backward, turning rubble into houses and cars, would likewise not violate the (generalized) second law.

Please do read this page (it is not hard to read, but here is an even simpler analysis of the compensation argument), and you will be astonished by how corrupt science can become when reviewers are “very, very vigilant” to protect consensus science from any opposing views. And you can decide for yourself who is promoting pseudoscience.

Granville Sewell

A new book from MIT Press, Pseudoscience: The Conspiracy Against Science,includes a chapter by Adam Marcus and Ivan Oransky, founders of the website Retraction Watch. In “Pseudoscience, Coming to a Peer-Reviewed Journal Near You,” I found my own name mentioned. They write:

Although one might assume that journals would hold a strong hand when it comes to ridding themselves of bogus papers, that’s not always the case. In 2011, Elsevier’s Applied Mathematics Letters retracted a paper by Granville Sewell of the University of Texas, El Paso, that questioned the validity of the second law of thermodynamics — a curious position for an article in a mathematics journal, but not so curious for someone like Sewell, who apparently favors intelligent design theories over Darwinian natural selection.

Did I really “question the validity of the second law”?

Accepted and Withdrawn

Well, let’s look at the abstract of the accepted but withdrawn-at-the-last-minute Applied Mathematics Letters (AML) article, “A Second Look at the Second Law”:

It is commonly argued that the spectacular increase in order which has occurred on Earth does not violate the second law of thermodynamics because the Earth is an open system, and anything can happen in an open system as long as the entropy increases outside the system compensate the entropy decreases inside the system. However, if we define “X-entropy” to be the entropy associated with any diffusing component X (for example, X might be heat), and, since entropy measures disorder, “X-order” to be the negative of X-entropy, a closer look at the equations for entropy change shows that they not only say that the X-order cannot increase in a closed system, but that they also say that in an open system the X-order cannot increase faster than it is imported though the boundary. Thus the equations for entropy change do not support the illogical “compensation” idea; instead, they illustrate the tautology that “if an increase in order is extremely improbable when a system is closed, it is still extremely improbable when the system is open, unless something is entering which makes it not extremely improbable.” Thus, unless we are willing to argue that the influx of solar energy into the Earth makes the appearance of spaceships, computers and the Internet not extremely improbable, we have to conclude that the second law has in fact been violated here.

In Section 3, I wrote:

The second law of thermodynamics is all about probability; it uses probability at the microscopic level to predict macroscopic change. Carbon distributes itself more and more uniformly in an isolated solid because that is what the laws of probability predict when diffusion alone is operative. Thus the second law predicts that natural (unintelligent) causes will not do macroscopically describable things which are extremely improbable from the microscopic point of view. The reason natural forces can turn a computer or a spaceship into rubble and not vice versa is probability: of all the possible arrangements atoms could take, only a very small percentage could add, subtract, multiply and divide real numbers, or fly astronauts to the moon and back safely…But it is not true that the laws of probability only apply to closed systems: if a system is open, you just have to take into account what is crossing the boundary when deciding what is extremely improbable and what is not.

Then, in my conclusion:

Of course, one can still argue that the spectacular increase in order seen on Earth does not violate the second law because what has happened here is not really extremely improbable… And perhaps it only seems extremely improbable, but really is not, that, under the right conditions, the influx of stellar energy into a planet could cause atoms to rearrange themselves into nuclear power plants and spaceships and digital computers. But one would think that at least this would be considered an open question, and those who argue that it really is extremely improbable, and thus contrary to the basic principle underlying the second law of thermodynamics, would be given a measure of respect, and taken seriously by their colleagues, but we are not.

Even if, as Marcus and Oransky believe, intelligent design were “pseudoscience,” my AML paper was still not pseudoscience. Why? Because it did not mention or promote intelligent design, and it did not question the second law, only the absurd compensation argument, which is always used to avoid the issue of probability when discussing the second law and evolution. But these authors apparently feel that it is pseudoscience to force Darwinists to address the issue of probability when defending their theory against the second law.

A Published Apology

Marcus and Oranski continue:

The article was retracted, according to the notice, “because the Editor-in-Chief subsequently concluded that the content was more philosophical than mathematical and, as such, not appropriate for a technical mathematics journal such as Applied Mathematics Letters.” Beyond the financial remuneration, the real value of the settlement for Sewell was the ability to say — with a straight face — that the paper was not retracted because it was wrong. Such stamps of approval are, in fact, why some of those who engage in pseudoscience want their work to appear in peer-reviewed journals.

Well, whether the article was appropriate for AML or not is debatable, but it was reviewed and accepted, then withdrawn at the last minute, as reported here. And since Elsevier’s guidelines state that a paper can only be withdrawn after acceptance because of major flaws or misconduct, yes, I wanted people to know that Elsevier did not follow its own guidelines, and that the paper was not retracted because major flaws were found, and that is exactly what the published apology acknowledged. Marcus and Oranski omit the first part of the sentence they quote from the apology, which states that the article was withdrawn “not because of any errors or technical problems found by the reviewers or editors.”

They conclude:

And it means that the gatekeepers of science — peer reviewers, journal editors, and publishers — need always be vigilant for the sort of “not even wrong” work that pseudoscience has to offer. Online availability of scholarly literature means that more such papers come to the attention of readers, and there’s no question there are more lurking. Be vigilant. Be very, very vigilant.

In a peer-reviewed 2017 Physics Essays paper, “On ‘Compensating’ Entropy Decreases,” I again criticized the widely used compensation argument, and again I did not question the validity of the second law or explicitly promote intelligent design. Here were my conclusions in that paper:

If Darwin was right, then evolution does not violate the second law because, thanks to natural selection of random mutations, and to the influx of stellar energy, it is not really impossibly improbable that advanced civilizations could spontaneously develop on barren, Earth-like planets. Getting rid of the compensation argument would not change that; what it might change is, maybe science journals and physics texts will no longer say, sure, evolution is astronomically improbable, but there is no conflict with the second law because the Earth is an open system, and things are happening elsewhere which, if reversed, would be even more improbable.

An Unfair Characterization?

And if you think this characterization of the compensation argument is unfair, read the second page (71) of the Physics Essays article and you will see that the American Journal of Physics articles cited there are very explicit in making exactly the argument that evolution is extremely improbable but there is no conflict with the second law because the Earth is an open system and things are happening outside which, if reversed, would be even more improbable. As I point out there, one can make exactly the same argument to say that a tornado running backward, turning rubble into houses and cars, would likewise not violate the (generalized) second law.

Please do read this page (it is not hard to read, but here is an even simpler analysis of the compensation argument), and you will be astonished by how corrupt science can become when reviewers are “very, very vigilant” to protect consensus science from any opposing views. And you can decide for yourself who is promoting pseudoscience.

Convergence v. Darwin

The Real Problem With Convergence

Biology is replete with instances of convergence — repeated designs in distant species. Marsupials and placentals, for instance, are mammals with different reproductive designs (placentals have significant growth in the embryonic stage attached to the nutrient-rich placenta whereas marsupials have no placenta and experience significant development after birth) but otherwise with many similar species.

The marsupial flying phalanger and placental flying squirrel, for example, have distinctive similarities, including their coats that extend from the wrist to the ankle giving them the ability to glide long distances. But evolutionists must believe that these distinctive similarities evolved separately and independently because one is a marsupial and the other is a placental, and those two groups must have divided much earlier in evolutionary history. Simply put, evolution’s random mutations must have duplicated dozens of designs in these two groups.

It is kind of like lightning striking twice, but for evolutionists — who already have accepted the idea that squirrels, and all other species for that matter, arose by chance mutations — it’s not difficult to believe. It simply happened twice rather than once (or several times, in the cases of a great many convergences).

What is often not understood, however, by evolutionists or their critics, is that convergence poses a completely different theoretical problem. Simply put, a fundamental evidence and motivation for evolution is the pattern of similarities and differences between the different species. According to this theory, the species fall into an evolutionary pattern with great precision. Species on the same branch in the evolutionary tree of life share a close relationship via common descent. Therefore, they share similarities with each other much more consistently than with species on other branches.

This is a very specific pattern, and it can be used to predict differences and similarities between species given a knowledge of where they are in the evolutionary tree.

Convergence violates this pattern. Convergence reveals striking similarities across different branches. This leaves evolutionists struggling to figure out how the proverbial lightning could strike twice, as illustrated in a recent symposium::

Does convergence primarily indicate adaptation or constraint? How often should convergence be expected? Are there general principles that would allow us to predict where and when and by what mechanisms convergent evolution should occur? What role does natural history play in advancing our understanding of general evolutionary principles?

It is not a good sign that in the 21st century evolutionists are still befuddled by convergence, which is rampant in biology, and how it could occur. This certainly is a problem for the theory.

But a more fundamental problem, which evolutionists have not reckoned with, is that convergence violates the evolutionary pattern. Regardless of adaptation versus constraint explanations, and any other mechanisms evolutionists can or will imagine, the basic fact remains: a fundamental evidence and prediction of evolution is falsified.

The species do not fall into the expected evolutionary pattern.

The failure of fundamental predictions — and this is a hard failure — is fatal for scientific theories. It leaves evolution not as a scientific theory but as an ad hoc exercise in storytelling. The species reveal the expected evolutionary pattern — except when they don’t. In those cases, they reveal some other pattern.

So regardless of where you position yourself in this debate, please understand that attempts to explain convergence under evolutionary theory, while important in normal science, do nothing to remedy the underlying theoretical problem, which is devastating.

Occam's razor v. Darwin II

A Suspicious Pattern of Deletions

Andrew Jones

Andrew Jones

Winston Ewert recently published a paper in BIO-Complexity suggesting that life is better explained by a dependency graph than by a phylogenetic tree. The study examines the presence or absence of gene-families in different species, showing that the average gene family would need to have been lost many times if common ancestry were true. Moreover, the pattern of these repeated losses exhibits a suspiciously better fit to another pattern: a dependency graph.

It turns out this pattern of nonrandom “deletions” has been noticed before, although it appears that the researchers involved didn’t realize they might be looking at a dependency graph. Way back in 2004, Austin Hughes and Robert Friedman published a paper titled“Shedding Genomic Ballast: Extensive Parallel Loss of Ancestral Gene Families in Animals.” (For more about Hughes, who passed away in 2015, see here in the online journal Inference.) From the Abstract:

An examination of the pattern of gene family loss in completely sequenced animal genomes revealed that the same gene families have been lost independently in different lineages to a far greater extent than expected if gene loss occurred at random.

The Nematode Genome

They noted that different aspects of the nematode genome suggest it belongs in different places on the tree of life. They argue that presence or absence of genes could be better for inferring phylogenetic relationships than sequence similarities, and they found that this method produced the standard phylogenetic tree with 100 percent bootstrap support. Yet they also found that many genes were “lost” in parallel, in multiple branches of the tree. One criticism of Ewert’s work is that this phenomenon might be due to missing data: not all genes in all species have been catalogued. But Hughes and Friedman used five whole genomes, and so they could argue that the pattern is real, not an artifact.

Hughes and Friedman also argue that horizontal gene transfer is a much less likely explanation, since it is rarely seen in animals, and it is made even more so by the fact that whether some gene families are “lost” or some are “extra,” the deviations from the tree are not distributed randomly.

Moreover, many of the gene families non-randomly “lost” were elements of the core machinery of the cell, including proteins involved in amino acid synthesis, nucleotide synthesis, and RNA-to-protein translation. Despite this, the researchers argued:

The fact that numerous gene families have been lost in parallel in different animal lineages suggests that these genes encode proteins with functions that have been repeatedly expendable over the evolution of animals.

Core functions that are also expendable? The researchers are implying that all the gene families were present in the common ancestor of all animals, that it had a massively bloated and inefficient metabolism, with multiple different pathways to do any particular synthesis, and then lost them over time because animals need to have an efficient metabolism. Okay, but why did it have all these extra pathways? And when are all the gene families supposed to have evolved? This shunts all evolutionary creative (complexity-building) events back to the biological Big Bang of the Cambrian explosion.

Ewert’s hypothesis explains the same data more simply: there never was a bloated ancestor, and those genes weren’t lost so many times. The pattern isn’t best explained by any kind of tree. It is best explained by a dependency graph.

And even still yet more primeval tech v. Darwin.

Omega-3 Nutrition Pioneer Tells How He Saw Irreducible Complexity in Cells 40 Years Ago

Evolution News | @DiscoveryCSC

On a new episode of ID the Future, Jorn Dyerberg, the Danish biologist and co-discoverer of the role of omega-3 fatty acids in human health and nutrition, talks with Brian Miller about finding irreducible complexity in cells forty years ago.

Download the podcast or listen to it here.

It wasn’t until he encountered ID researchers like Michael Behe that he gave it that name — but he saw how many enzymes and co-enzymes it took working together to make metabolism work in every living cell. And if neo-Darwinism is true, and these enzymes showed up one at a time, “And over these eons, the other enzymes would just be sitting there waiting for the next one to come.”

Evolution News | @DiscoveryCSC

On a new episode of ID the Future, Jorn Dyerberg, the Danish biologist and co-discoverer of the role of omega-3 fatty acids in human health and nutrition, talks with Brian Miller about finding irreducible complexity in cells forty years ago.

Download the podcast or listen to it here.

It wasn’t until he encountered ID researchers like Michael Behe that he gave it that name — but he saw how many enzymes and co-enzymes it took working together to make metabolism work in every living cell. And if neo-Darwinism is true, and these enzymes showed up one at a time, “And over these eons, the other enzymes would just be sitting there waiting for the next one to come.”

Saturday, 25 August 2018

And still yet more primal tech v. Darwin.

Enzymes Are Essential for Life; Did They Evolve?

Olen R. Brown

Editor’s note: We are delighted to welcome a new contributor, the esteemed microbiologist Olen R. Brown. Among other distinctions, Dr. Brown is Professor Emeritus at the University of Missouri.

Olen R. Brown

Editor’s note: We are delighted to welcome a new contributor, the esteemed microbiologist Olen R. Brown. Among other distinctions, Dr. Brown is Professor Emeritus at the University of Missouri.

Darwinian evolution, even in its 21st-century form, fails the formidable task of explaining how the first enzyme arose. Evolution also fails to explain how the first enzyme was changed into the approximately 75,000 different enzymes estimated to exist in the human body or the 10 million enzymes that are thought to exist in all of Earth’s biota. Join me in a legitimate process in science, one made popular by Albert Einstein. It’s called a Gedanken — a thought experiment. Let us see if evolution meets the challenge of logic required if it is to explain how enzymes came to be.

Enzymes have what seem to be near-miraculous abilities. They are catalysts that greatly accelerate reactions by providing an alternate reaction pathway with a much lower energy barrier. Thus, although they do not create new reactions, they greatly enhance the rate at which a particular substrate is changed into a particular product. Every chemical reaction in the cell that is essential to life is made possible by an enzyme. Richard Wolfenden has concluded that a particular enzyme required to make RNA and DNA enormously speeds up the process.1 Without the enzyme, this reaction is so slow that it would take 78 million years before it happened by chance. Another enzyme, essential for making hemoglobin found in blood and the chlorophyll of green leaves, enormously accelerates an essential step required for this biosynthesis. Wolfenden explains that enzyme catalysis allows this step in biosynthesis to require only milliseconds but 2.3 billion years would be required without the enzyme. These enormous differences in rates are like comparing the diameter of a bacterial cell to the distance from the Earth to the Sun.

Regenerating ATP

Think of the enormous number of different chemical reactions required for life. Now, focus on only one such reaction, the need to regenerate ATP — the energy source for all life processes. As Lawrence Krauss has written, “The average male human uses almost 420 pounds of ATP each day … to power his activities… there is less than about 50 grams of ATP in our bodies at any one time; that involves a lot of recycling… each molecule of ATP must be regenerated at least 4,000 time each day.”2 This means that 7 x 1018 molecules of ATP are generated per second. By way of comparison, there are estimated to be only 100 billion stars (1 x 1011) in our galaxy, the Milky Way. To efficiently regenerate a molecule of ATP (recharging the cell’s battery) requires a specific enzyme. To create a molecule of ATP is even more complex. The citric acid cycle is only one important part of this process and it has eight enzymes. As the name “cycle” implies, these enzymes must function in sequence. The absence of any one enzyme stops the process. How the interdependent steps of a cycle can originate is left without explanation. Life in Darwin’s hopeful, warm, little pond is dead in the water.

Obviously, in seeking to explain how enzymes arose and diversified, the evolutionist must use the processes of evolution. It is proposed, and I concede it as possible, even logical, that the gene coding for an essential enzyme could be duplicated and the duplicated gene could be expressed as a mutation. The protein coded by this duplicate gene might catalyze a slightly different reaction. There are known examples, but they produce only slight differences in products or reaction mechanisms. Consequently, a mutation can introduce only very limited changes in a specific protein. This limits the scope of change to triviality compared to the scope required by evolution.

“There Was a Little Girl…”

I am reminded of a poem. “There was a little girl, and she had a little curl, right in the middle of her forehead. When she was good, she was very, very good, and when she was bad she was horrid.”3 The power of genetic mutation as a source of change for evolution is like the little girl in this poem. It is good (even very good) at explaining what it can explain — trivial changes — but horrid at explaining any changes needed for the evolution of species. Likewise, natural selection is ineffectual as an editor for evolution. (See “Gratification Deferred”,4 in my book The Art and Science of Poisons.)

Thus, scientific evidence is entirely lacking for the notion that enzymes arose by chance. The idea is ludicrous. This is true even if a primeval solution contained all the twenty amino acids of proteins but no genes and no protein-synthesizing machines. Ah, but, you may say, the Nobel laureate George Wald has written5: “Most modern biologists, having reviewed with satisfaction the downfall of the spontaneous generation hypothesis, yet unwilling to accept the alternative belief in special creation, are left with nothing.” He also wrote (on the same page): “One has only to contemplate the magnitude of this task to concede that the spontaneous generation of a living organism is impossible. Yet here we are as a result, I believe, of spontaneous generation.” In the same article he wrote: “Time is in fact the hero of the plot… the ‘impossible’ becomes possible, the possible probable, and the probable virtually certain. One has only to wait: time performs the miracles.” To be fair, Wald puts the word “impossible” in quotation marks. One may believe this, but surely it is beyond the logical meanings of words and concepts — and Wald appeals to “miracles,” does he not?

Time for a Gedanken

With this quandary, should not today’s scientist be allowed a Gedanken? Formerly, from at least the time of Aristotle, it was generally thought that organic substances could be made only by living things — one definition of vitalism. Frederick Wöhler’s laboratory synthesis of urea in 1828 was startling evidence incompatible with this idea. Perhaps a new look at the essential differences between life and non-life could be instructive. Not to be misunderstood, I do not mean to advocate for vitalism in its old sense, but simply to recognize the vast differences between non-living matter and a living cell in light of today’s knowledge of molecular biology. That a void exists in understanding this difference cannot be denied.

Astronomy, physics, and chemistry have laws that are useful for calculating and making predictions and, to a degree, even as explanations. The high school student can state the law of gravity and make calculations. The professor can do little more to explain this, or any, law of nature. Are not all natural laws, considered as explanations, only tautologies in the end? How is information content that is designed in a law made manifest in nature? Do laws disclose innate properties of energy, matter, and space-time?

Scientists are permitted to propose laws that mathematically describe fundamental particles and their behaviors without being stigmatized as appealing to the supernatural. Why should this not be acceptable in biology? Let us ponder the origin of enzymes and begin a conversation about the laws required to permit complexification in life. A starting place is the admission that perhaps things that appear to be designed are, in fact, designed. How this design occurs is surely a subject for scientific investigation, no more to be disallowed than is the use of laws in physics, astronomy, and chemistry to guide mathematical understanding of complex outcomes.

Notes:

- Richard Wolfenden. “Without enzymes, biological reaction essential to life takes 2.3 billion years.”

- Lawrence M. Krauss. Atom, an Odyssey from the Big Bang to Life on Earth… and Beyond. 1st ed., Little, Brown and Company 2001.

- Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. “There Was a Little Girl,” Vol. I: Of Home: Of Friendship, 1904.

- Olen R. Brown. The Art and Science of Poisons. Chapter 3, “The Dawnsinger.” Bentham Science Publishers.

- George Wald. “The Origin of Life,” Scientific American, August 1954, pp 46, 48.

Saturday, 18 August 2018

Sunday, 12 August 2018

Yet more on Darwinism's non-functional crystal ball.

Failed Predictions Weekend: Hunter on Darwinian Evolution, the DNA Code, and More

Evolution News | @DiscoveryCSC

e trust you are enjoying your weekend! On a classic episode of ID the Future, our Evolution News contributor Dr. Cornelius Hunter has more to say about his website Darwin’s Predictions, which critically examines 22 basic predictions of evolutionary theory.

In this second podcast of the series, Dr. Hunter discusses the uniqueness of DNA code and differences In this second podcast of the series, Dr. Hunter discusses the uniqueness of DNA code and differences in fundamental molecules. Listen to episode or download it here.

Evolution News | @DiscoveryCSC

e trust you are enjoying your weekend! On a classic episode of ID the Future, our Evolution News contributor Dr. Cornelius Hunter has more to say about his website Darwin’s Predictions, which critically examines 22 basic predictions of evolutionary theory.

In this second podcast of the series, Dr. Hunter discusses the uniqueness of DNA code and differences In this second podcast of the series, Dr. Hunter discusses the uniqueness of DNA code and differences in fundamental molecules. Listen to episode or download it here.

There is no such thing as engineerless engineering.

Modern Software and Biological Organisms: Object-Oriented Design

Walter Myers III

Walter Myers III

In my last post, I discussed the problem with “bad design” arguments. I also offered a defense of design theory by demonstrating the exceeding intricacy and detail of the vertebrate eye as compared to any visual device crafted by even the brightest of human minds. In fact, when we examine the various kinds of eyes in higher animals, we see the same modern object-oriented software design principles that computer programmers use to build the applications we use every day. That includes the executing code of the browser that displays this article. Formal object-oriented programming, as a method used by humans, has only been around since the 1950s Yet it is clearly represented in the biological world going back to the appearance of the first single-celled organisms 3.5 billion years ago (in the form of organelles such as the nucleus, ribosome, mitochondria, Golgi apparatus, etc.).

The Eye in Higher Animals

Let’s consider the eye, which is but one of many subsystems (along with the brain, heart, liver, lungs, etc.) in higher animals that coordinate their tasks to keep an organism alive. I discussed as much in a previous article comparing the code of modern computer operating systems to the DNA code that is executed to build and maintain biological organisms. In computer programming, it is a very bad practice to write code willy-nilly and expect it to perform a useful function. Highly complex computer programs are always specified by a set of requirements that outline the functionality, presentation, and user interaction of the program. Each of these is generally called a functional specification. (Modern agile software development techniques many teams use now are more of an evolutionary process, but still require working from a backlog of requirements through progressive short iterations.)

With respect to the eye in organisms such as chordates, molluscs, and arthropods, the functional requirements (or backlog, in agile terms) might, at a high level, look like this:

Collect available light

Regulate light intensity through a diaphragm

Focus light through lenses to form an image

Convert images into electrical signals

Transmit signals to the visual processing center of the brain

Process visual detail, building a representation of the surrounding environment

This set of specifications should not be taken lightly. To presume that blind, undirected processes can generate novel functionality solving a highly complex engineering problem, as we see above, is highly fanciful. These specifications call for an appropriate interface of the eye (in this case, the optic nerve) that connects it with the visual cortex. They call for a visual cortex that will process the images, which must then interface with a brain that can subsequently direct the whole of the organism to respond to its environment.

Human designers can only crudely approximate any of this. Yet, as complex as the eye might be, it is one small but critical component of the entire system that makes up a higher biological organism. What’s more, in the design of complex systems, the set of requirements must map to an architecture that defines the high-level structure of the system in terms of its form and function, promoting reuse of component parts across different software projects. We see such component reuse in biological organisms, with different eye types as a potent example.

A Range of Eye Layouts

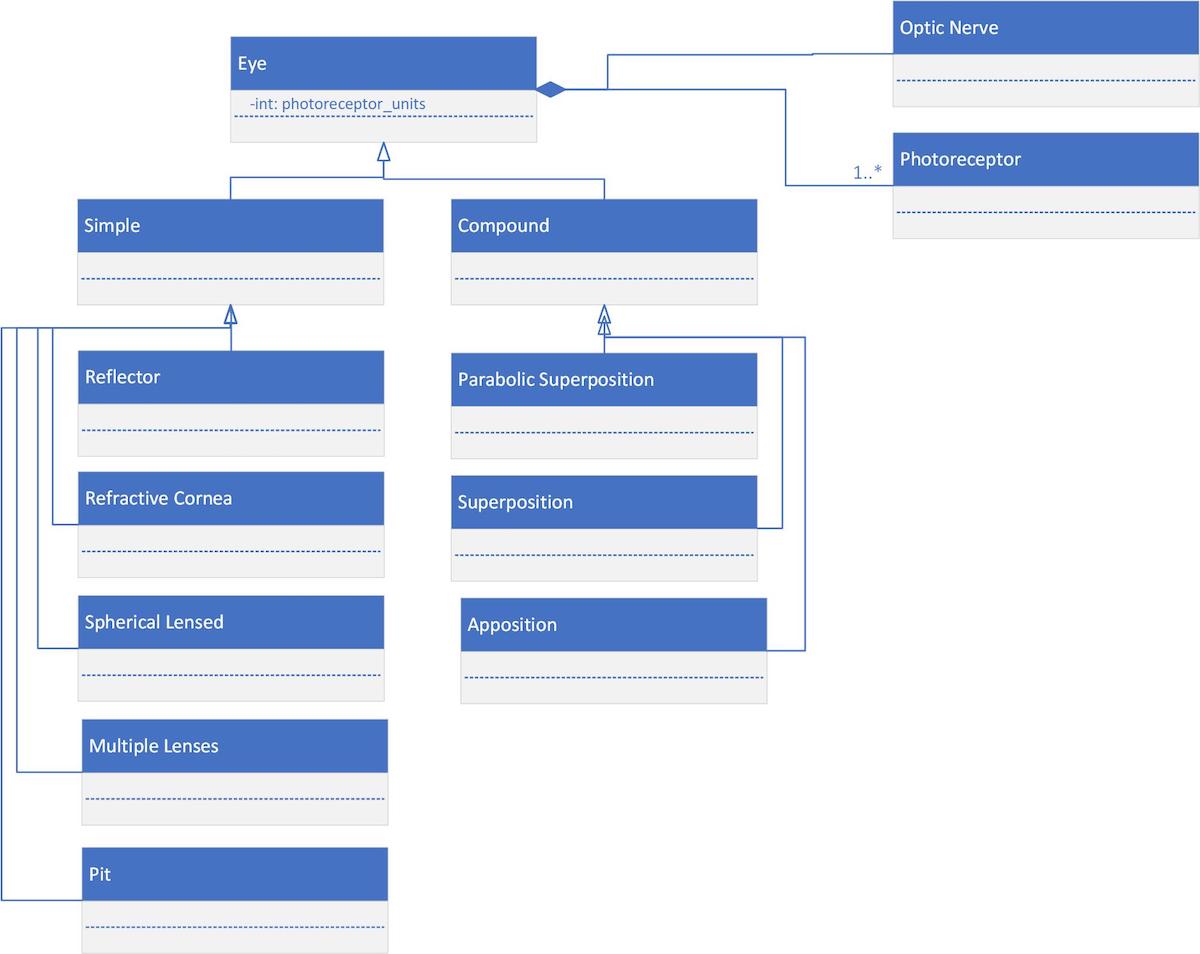

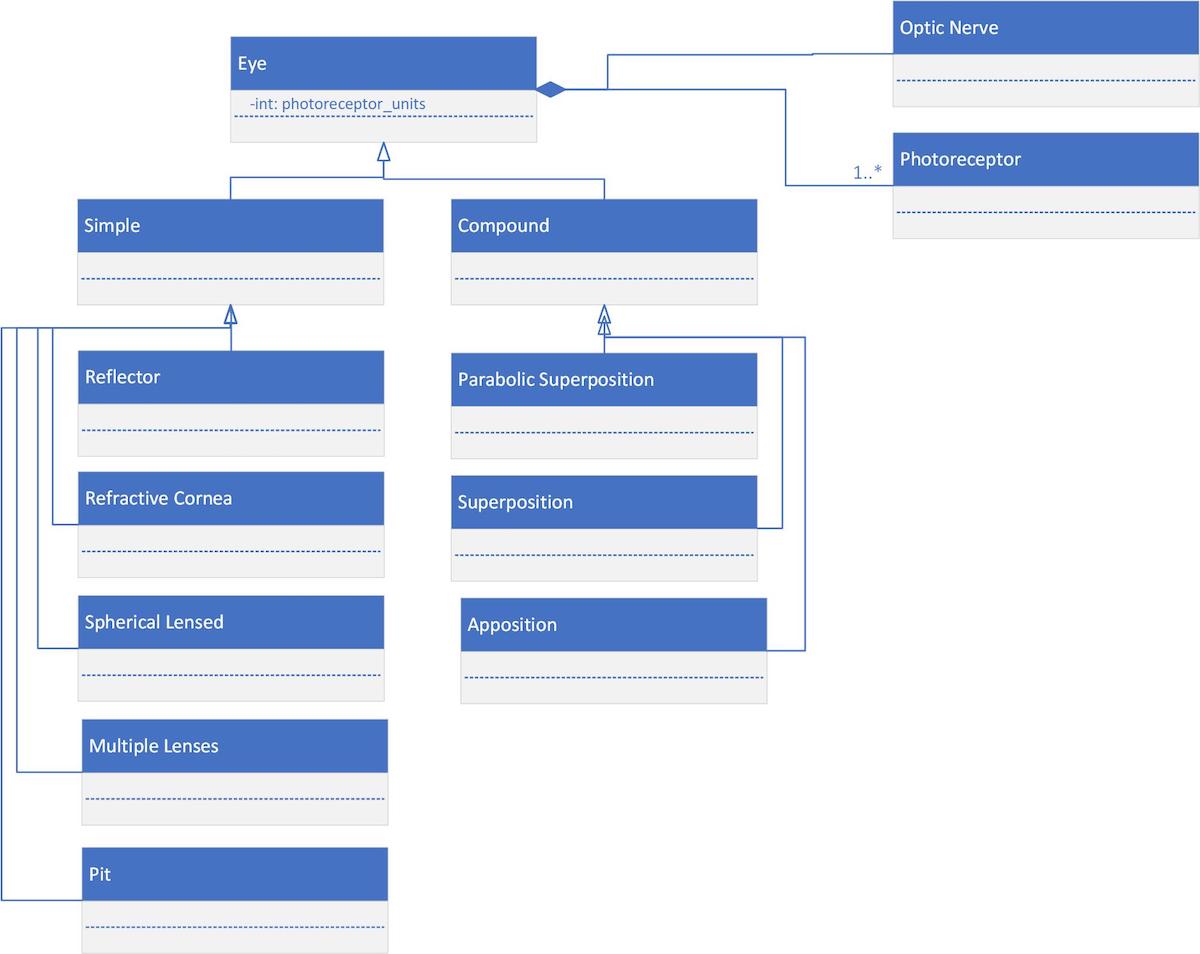

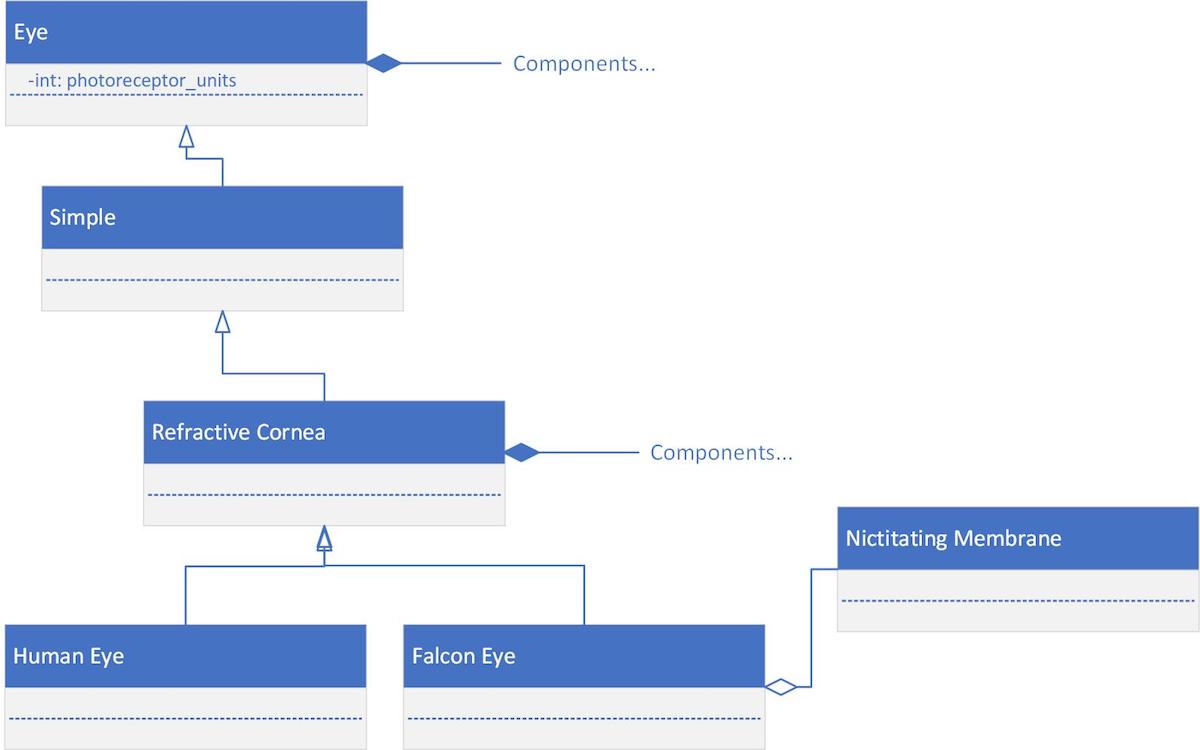

Scientists believe there are basically ten different eye layouts (designs) that occur in nature. From a computational perspective, we can view this generally as a three-level, object-oriented hierarchy that can describe animal eyes, as seen in the class diagram below.

At the top level, we have the Eye class which, for the sake of simplicity, is composed minimally of a collection of one or more photoreceptors and an optic nerve that transmits images to the visual cortex. (Note the filled diamond shape that represents composition in relationships between whole and part.) The Eye class itself is “abstract” in the sense that it cannot be instantiated itself, but provides the properties needed by all its subclasses that at some level will be instantiated as an eye of some given type. On the second level, we have the Simple and Compound eye types which have an inheritance relationship with the Eye class. This means these two eye types inherit all the properties of the abstract Eye base class, along with its necessary components. These classes are abstract as well. On the third level, we have class objects that inherit all the properties of either the Simple or Compound classes. At this level we still have abstract classes which will have all the properties or components necessary to exist in any given higher animal but require further differentiation at the species level to be properly instantiated.

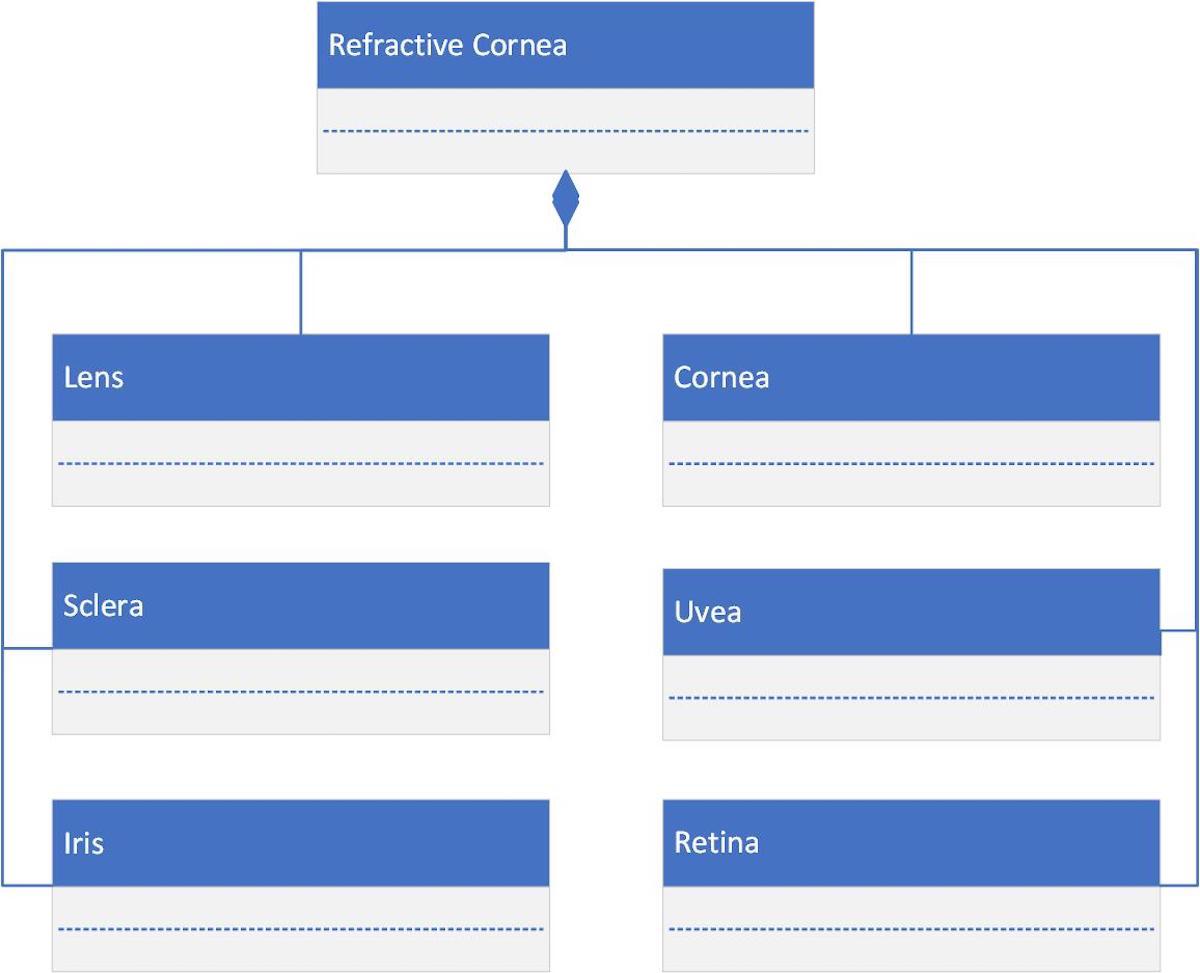

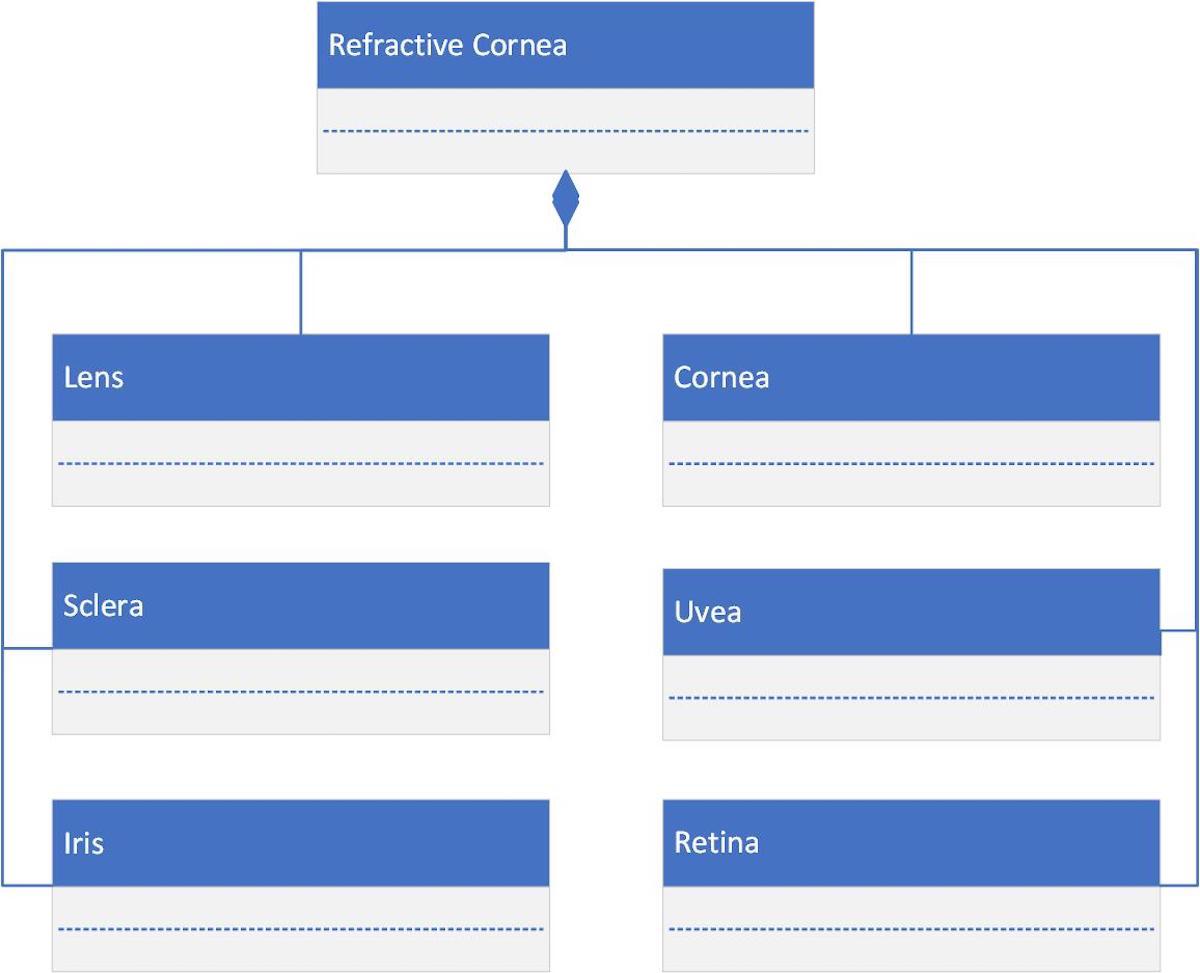

Now let’s take a closer look at the Refractive Cornea eye layout, which is present in most mammals, birds, and reptiles. The Refractive Cornea class diagram below shows the major components of which it is composed, which are a lens, sclera, iris, cornea, uvea, and retina.

Humans and Falcons

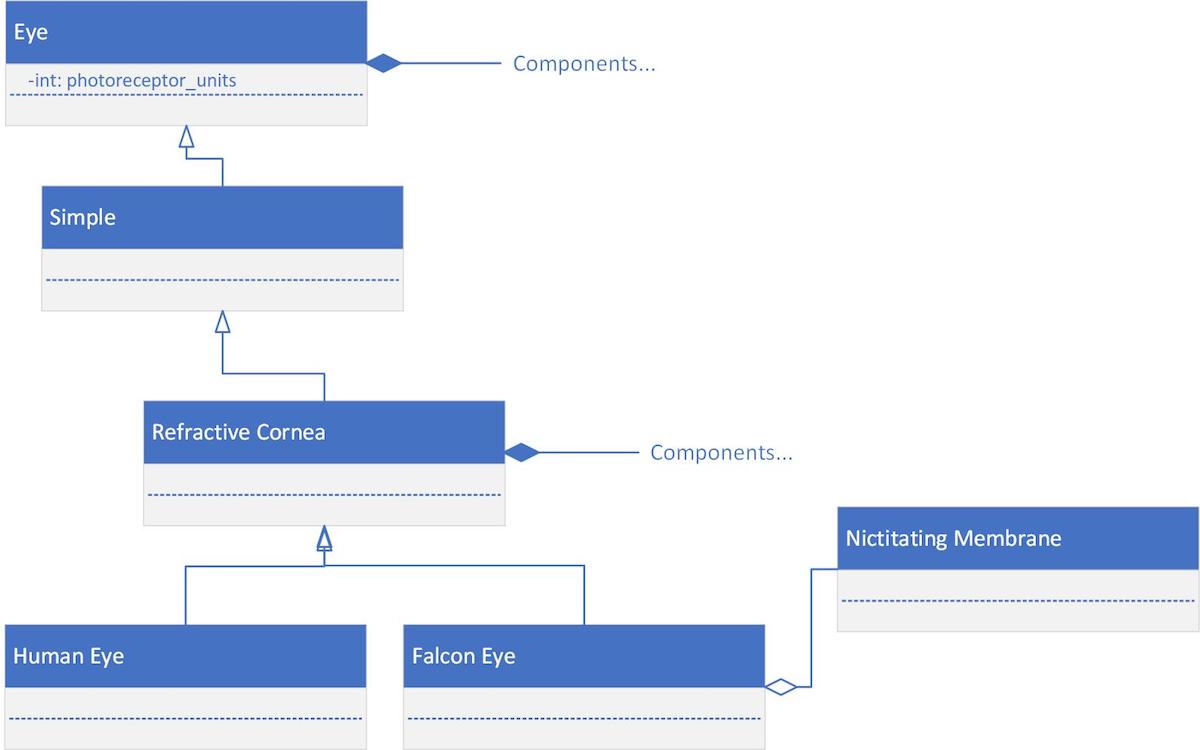

What is important is not just the particular parts, but structurally how these parts are uniquely instantiated in animal species with refinements based on the requirements specific to the habitat in which they live. For example, even though humans and falcons have the same basic components of the refractive cornea eye type, structurally they are quite different, as seen here.

The requirements of a falcon’s refractive cornea eye type include that it be able to find its prey over great distances. This means that, as compared to humans, it needs a larger lens, more aqueous humor to nourish the cornea, a more convex retina, and a higher concentration of light-gathering cones. To aid high speed hunting dives, which can surpass 200 miles per hour, the falcon eye also sports a translucent nictitating membrane (third eyelid) to clear any debris on dives and also keep the eye moist. At the component level of the refractive cornea, though humans and falcons share similar components in the abstract, there are significantly different architectural properties and functions that must be implemented by direction of the DNA code possessed by each organism.

So, let’s now look at the simplified class hierarchy for human and falcon eyes. At the level of instantiation, where we find the Human Eye and Falcon Eye classes below, they must implement the component interfaces of the Eye and Refractive Cornea specific to their species. In the case of the Falcon Eye class, it also aggregates the Nictitating Membrane class that is associated with it as a species (and other species of birds as well, such as the bald eagle).

Convergent Evolution?

I’m certain Darwinian evolutionists will argue that this class diagram construction is simply one that comes after the fact, and only supports what is described as convergent evolution across species, where unrelated organisms evolve similar traits based on having to adapt to the habitats in which they find themselves. Indeed, evolutionary biologists believe the eye, which they admit is precisely engineered, evolved independently more than fifty times.

Yet, when we compare highly complex computer software programs to biological organisms, even the most complex software programs designed by literally the best PhD minds on the planet pale in comparison with the simplest of biological organisms. To say that evolution, which is blind, undirected, and counts fully on fortuitous random mutations, will solve the same engineering problem multiple times through what is essentially mutational luck is unrealistic given statistically vanishing probabilities over the short timelines of even hundreds of millions of years. However, when we look at the various eye designs as discussed here, it is clear they each meet a set of specific requirements, following principles of object-oriented design we would expect from a master programmer.

Saturday, 11 August 2018

1st century Rabbinic teachings on annihilationism

Worms and Fire: The Rabbis or Isaiah?

by Glenn Peoples ·

Imagine that you had never heard of “hell.” The eternal misery of the damned in dungeons of fire, Dante’s Inferno, Jonathan Edwards’ classic sermon, “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God,” you hadn’t heard of any of it. And now imagine that you were about to open a book that tells us what the judgement of God on his enemies will be like. You read this:

The LORD will come in fire, and his chariots like the whirlwind, to pay back his anger in fury, and his rebuke in flames of fire. For by fire will the LORD execute judgement, and by his sword, on all flesh; and those slain by the LORD will be many. From new moon to new moon, and from sabbath to sabbath, all flesh shall come to worship before me, says the LORD. And they shall go out and look at the dead bodies of the people who have rebelled against me; for their worm shall not die, their fire shall not be quenched, and they shall be an abhorrence to all flesh. (Isaiah 66:15-16, 23-24)

It’s pretty fearsome stuff, granted, but beyond that, what would you make of it? Endless suffering? Torment forever in the fires of hell? Not likely. Such ideas would never even occur to you when reading a passage like this. Anyone able to read the above passage can see what it describes: Death. Any claim that Isaiah 66 contains anything that would lend support to the doctrine of the eternal torments of the damned in hell is indefensible, even laughable. You cannot find a doctrine like that in this text on the basis of any standard methods of responsible exegesis.

But things do not end there when it comes to this text in Isaiah 66. As those familiar with the evangelical discussion of final judgement are well aware, Jesus is said to have quoted this passage when teaching people to avoid sin. In the Gospel of Mark, this teaching of Jesus marks his first use of the word Gehenna, literally referring to the Valley of Hinnom (it is the Greek equivalent of Gehinnom, “valley of Hinnom” in Aramaic). Mark 9:47-48 reads,

If your eye causes you to sin, tear it out. It is better for you to enter the kingdom of God with one eye than with two eyes to be thrown into hell, ‘where their worm does not die and the fire is not quenched.’

If all we knew about Jesus’ teaching on hell is that he said this and where he got it, there could be no doubt what he is saying. Sin is so serious that we would be better off without an eye that leads us into sin, than to lose not only our eye, but our entire self in Gehenna, ending up like those enemies of God in Isaiah 66 – dead and gone. Outside of disputes of the doctrine of hell, New Testament commentators apparently see this without difficulty. Commenting on Mark 9:48, R. Alan Cole notes that

The Old Testament context (Is. 66:24) helps to explain this solemn imagery. It has reference in Isaiah to “the dead bodies of the men who have rebelled against me.” Gehenna, the eternally smouldering rubbish-dump outside Jerusalem, is the symbol of the final state of those who have rebelled against God, amongst whom Jesus warns us that we may find ourselves, unless we enter God’s kingdom (verse 47), equated with life (verse 45).1

The point, then, is not that the valley of Hinnom is hell (in fact that the valley was a smoldering rubbish dump is itself difficult to establish from any reputable source). Rather, it is a fitting symbol, illustrating what final judgement is like. Jeremiah referred to the valley of Hinnom in terms of slaughter and death (see later). More importantly, Isaiah 66 (which does not mention the Valley of Hinnom), as Hare notes, explains Mark 9. It refers to dead bodies, to those who miss out on life in the end.

Reflecting on the way this passage is frequently used in traditional theology, Douglas Hare advises us that

It is clear in the Isaiah passage that the apostates whose worm and fire are unending are “dead bodies.” There is no suggestion that these evil persons will suffer eternally; their carcasses will remain indefinitely as a reminder of their rebellion against God.2

I think in general terms Hare has it right, but how can carcasses “remain indefinitely” – especially those being consumed by maggots and/or fire? In Isaiah 66, a reasonable inference is that we are being shown how such language can be used – to stress permanence and irreversibility. But the point is clear. Jesus is using Isaiah to make a point, and unless he is intentionally meaning something fundamentally different from what Isaiah said – but not telling anyone that he was doing so (hardly a helpful teaching tactic) – we have in Mark 9 nothing to suggest that Jesus taught the doctrine of the eternal torments of the damned in hell. Even when Jesus also refers to an “unquenchable fire” (9:43), this overall appearance is not changed. After all, fires so large and fierce that they cannot be quenched (put out by people fighting it) can still, after they have run out of fuel, burn out. Indeed, the Old Testament clearly speaks of unquenchable fires in exactly this way, as seen in Ezekiel 20:47-48.

[S]ay to the forest of the Negeb, Hear the word of the LORD: Thus says the Lord God, I will kindle a fire in you, and it shall devour every green tree in you and every dry tree; the blazing flame shall not be quenched, and all faces from the south to the north shall be scorched by it. All flesh shall see that I the LORD have kindled it; it shall not be quenched.

It seems clear enough that what is in view (whether the picture itself is literal or figurative) is a blazing fire that will destroy the forest, and nobody is going to save the forest, because the fire will not be quenched by anyone. So the language of unquenchable fire in Mark’s Gospel does not suggest endless suffering any more than it did in Isaiah. Bearing this in mind, Morna Hooker is right to say, commenting on Mark 9, that “It should be noted that nothing is said here about eternal punishment: on the contrary, the image seems to be one of annihilation, in contrast to life; it is the fire, and not the torment, which is unquenchable.”3

So far, so good. The facts aren’t complicated, so it’s a straightforward matter: Isaiah 66 does not teach eternal torment, but actually teaches something resembling annihilationism. One day God will judge his enemies and destroy them, leaving them dead. Jesus quoted Isaiah in passing, indicating what he thought the final judgement of God would be like. So, one would think, Jesus probably agreed with all this. Why quote a passage of the Bible to make your point when you don’t agree with it? But as is no secret, when we turn from the biblical commentaries and to the polemical works advocating the traditional view of hell, we see that plenty of evangelicals don’t interpret Jesus this way. Instead, they see his reference to fire and worms as a reference to the sufferings of the damned throughout eternity. What then do they make of the above evidence? In truth, many of them make nothing of it, and are surprised to discover it. Anecdotally, most evangelicals I have spoken to who believe in the eternal torment of the damned don’t actually realise that Jesus is quoting from Isaiah, let alone know what Isaiah 66 is about. But in the literature, some have realised that their theology has a problem on its hands that needs to be resolved. If traditionalists are to preserve any interpretation of Mark 9 that does not undermine the doctrine of eternal torment, a question plainly needs to be answered: Why would Jesus quote a Scripture that so clearly does not indicate eternal torment but actually indicates annihilation, when his intention was to teach eternal torment and not annihilationism?

It’s a pickle, but one solution has been proposed: Regardless of whether or not Isaiah 66 offers support for the doctrine of eternal torment, other books among Jewish literature modified Isaiah’s imagery to refer to eternal torment. When Jesus quoted from Isaiah, although he didn’t mention any of these other books or what they had to say, his audience would have been familiar with the literature, they would have known of the references to divine judgement in those other books, and so when they heard Isaiah being quoted, they would have filtered what they heard through what they knew about the other books that spoke about divine judgement, and they would have therefore interpreted Jesus as referring to eternal torment, rather than to the conquest and death that Isaiah spoke about.

Several Evangelical theologians have suggested this line of argument while defending the doctrine of the eternal torments in hell. Peter Head’s approach is representative:

Is it possible that the recent emphasis on the completeness of the destruction is an over-reaction? Certainly Jewish thought, relating Isaiah 66:24 to passages of Judgment promised in the valley of Hinnom (e.g. Jeremiah 7:32; 19:6f.), related Gehenna to the place of eternal punishment. The language of Gehenna, chosen by Jesus, echoes this tradition and suggests a durative aspect to the unquenchable fire and continuing destructive activity of the worm. A thorough study of the influence of Isaiah 66:24 within second temple Judaism would also be a useful (and large) research project. Some clear examples in which Isaiah 66:24 functions to support statements of eternal duration for judgment include: Judith 16:17: ‘Woe to the nations that rise up against my people! The Lord Almighty will take vengeance on them in the day of judgement; fire and worms he will give to their flesh; they shall weep in pain for ever.’ 1 Enoch 27:2ab-3: ‘This accursed valley is for those accursed forever; here will gather together all (those) accursed ones, those who speak with their mouth unbecoming words against the Lord and utter hard words concerning his glory. Here shall they be gathered together, and here shall be their judgement, in the last days. There will be upon them the spectacle of the righteous judgement, in the presence of the righteous forever. The merciful will bless the Lord of Glory, the Eternal King, all the day.’ Cf 1 Enoch 54:1-6: a deep valley burning with fire where kings and rulers were to be imprisoned with iron chains, cast into ‘the abyss of complete condemnation’. In the Sibylline Oracles 1.103, Gehenna is associated with ‘terrible, raging, undying fire’; in 11.292 Gehenna is associated with God’s terrible judgments; it is described (paradoxically) as a place of darkness, it is the place of punishment for the wicked angels (the Watchers; cf 1 Enoch 10:13; 18:11) and extended to sinful humanity (cf 1 Enoch 90:23f.).4

In arguing that Jesus was really endorsing the doctrine of eternal torment in spite of using Isaiah 66 and its reference to dead bodies, Robert Yarborough simply makes reference to Head’s article, assuming that it settles the matter of Jesus assuming a later tradition of interpretation. In the 19th century Alfred Edersheim suggested a similar line of argument, which Robert Morey included in his 1984 work defending the traditional view.5 I may as well admit up front that the above argument looks implausible from the outset to me. The idea that although Jesus is quoting a text that says nothing about eternal torment, we should still interpret Jesus as meaning to refer to eternal torment because his audience would have known that some other books referred to eternal torment, looks to me like an undignified effort to get Jesus to say something he clearly did want to not say. It would be wrong of me to suggest, then, that I’m quite open to this interpretation. I’m not. That being said, I want to explain why I don’t think this argument has anything going for it. In doing so I need to answer a number of questions:

Is it true that there was one (more or less) universally held view on final punishment in Jesus’ day?

Is it true that Jewish literature did not just teach eternal torment, but actually interpreted Isaiah 66 as doing so?

What effect, if any, does the notion of canonicity have on the way that we address this issue?

What role does the reader response (or hearer’s response) play in constructing the meaning of what a speaker or author says?

There are probably other questions to ask here, but I think these four are the most important, because the argument in question relies rather heavily on specific answers to these questions being the right ones. For each of these questions that Head, Yarborough and others answer wrongly, their argument becomes weaker (in fact I maintain that a wrong answer to any of these questions will render the argument highly implausible). Let’s turn to each of them now.

Is it true that there was one (more or less) universally held view on final punishment in Jesus’ day?

Implicit in this argument is the belief that when a first century Jewish audience heard reference to Gehenna and to Isaiah’s foreboding of divine judgement, there is a specific idea that we should have expected them to all latch onto, one view of hell that they would all have had a shared understanding of and that would have come to mind for all of them.

This argument requires this assumption, or else it fails. After all, if there potentially existed a range of views on final punishment in Jesus’ audience, then there is no reason to think that just referring to Isaiah’s prophecy would have prompted them to think of the eternal torments of the damned in hell. Remember, this was not a teaching from Jesus on the nature of hell. Not at all It was moral teaching on how we should strive to avoid sin, because hell is such a bad thing. But nothing is added, and no question about what hell is like is answered in Mark 9. Isaiah is doing all that work. On hearing his words, is there a common view to which people could immediately assume that Jesus was making reference to?

The rather naïve expectation to be able to look back into first century history and easily find one true and universally held Judaism is not something any historian would presume to do. On the contrary, “Examining all evidences of … Judaism, within some broad limits, we find everything and its opposite.”6 As Scott summarises things,

The intertestamental documents provide inescapable evidence of the variety that characterized first-century Judaism. There was a common Jewish religious-historical heritage based on the OT. But through four eventful centuries numerous groups arose with different understandings of the OT and whose conceptions and practical expressions of religion were at variance with each other. So widespread was the diversity within Second Commonwealth Judaism that it is almost impossible to speak dogmatically about the pre-Christian Jewish view of anything.7

Nor, for that matter, am I attributing that belief to those who make this argument about hell. But whether they believe it when pressed for an answer or not, the argument certainly seems to require something like it when it comes to questions of the world to come.

In fact some Jewish thinkers interpreted parts of the Old Testament to suggest that the lost – or some of them at least, will not even rise again to face judgement:

“The generation of the wilderness has no portion in the world to come and will not stand in judgment, for it is written, ‘In this wilderness they shall be consumed and there they shall die’ (Numbers 14:35),” the words of R. Aqiba. Y R. Eliezer says, “Concerning them it says, ‘Gather my saints together to me, those that have made a covenant with me by sacrifice’” (Psalms 50:5). “The party of Korah is not destined to rise up, for it is written, ‘And the earth closed upon them’ – in this world.”8

The diversity of opinion that existed in the “intertestamental literature,” the Jewish literature composed in the centuries leading up to the first century AD, is widely acknowledged even by those who reject annihilationism: “The intertestamental literature constructed divergent scenarios for the wicked dead, including annihilation (4 Ezra 7:61; 2 Apoc Bar 82:3ff.; 1 Enoch 48:9; 99:12; 1QS iv. 11-14 ) and endless torment (Jub 36:11; 1 Enoch 27:1-3; 103:8; T Gad 7:5).”9 Reading through these examples verifies this diversity. To pick an example, the passage cited from 2 Baruch claims that the lost will be like “vapour,” and that “as smoke they will pass away.” By contrast, Jubilees 36:10 states – using noticeably less biblical language than 2 Baruch – that those who devise evil against others will “depart into eternal execration; so that their condemnation may be always renewed in hate and in execration and in wrath and in torment and in indignation and in plagues and in disease for ever.”

Even while making the argument that Jesus’ audience must have interpreted him to be referring to eternal torment, Edersheim concedes that the doctrine of annihilationism (although he does not name it) existed in the work of very influential rabbis. He acknowledges that in the view of Rabbi Hillel, many sinners of Israel and of the Gentiles are “tormented in Gehenna for twelve months, after which their bodies and souls are burnt up and scattered as dust under the feet of the righteous,” a comment in the Talmud that is doubtless influenced by the teaching on divine judgement found in Malachi 4:3 (“You will tread down the wicked, for they will be ashes under the soles of your feet on the day which I am preparing”). However a small number of this group, Hillel claimed, would suffer forever instead. And on this basis Edersheim notes, “However, therefore, the school of Hillel might accentuate the mercy of God, or limit the number of those who would suffer eternal punishment [by which Edersheim more specifically means eternal torment], it did teach eternal punishment in the case of some. And this is the point in question.”10 However, this is not the point in question. After all, Edersheim and all who hold the traditional view must say that Hillel was half wrong. He taught that great numbers of sinners would be finally annihilated, and as such it is the case that annihilationism, was a well known and honorable teaching in the time of Jesus, and therefore references to hellfire and judgement certainly cannot be assumed to preclude annihilationism. And yet, almost incredibly, Edersheim moves directly from this observation to this claim: “But, since the schools of Shamai and Hillel represented the theological teaching in the time of Christ and His Apostles, it follows that the doctrine of eternal punishment [again, here meaning eternal torment] was held in the days of our Lord, however it may afterward have been modified. Here, so far as this book is concerned, we might rest the case.” Rest the case! After showing that according to a Rabbi whose teaching was highly influential in the time of Jesus, the punishment of many of the lost consisted of annihilation?

Edersheim can be excused, up to a point. Speaking more generally on the use of intertestamental literature in New Testament studies, J. Julius Scott points out notes that as Edersheim simply did not have access to the Dead Sea Scrolls that we can now consult for ourselves, he engaged in “using Talmudic and similar writings uncritically and assuming for the New Testament era concepts and practices that arose centuries later.” This is a “methodological error that limits the reliability and usefulness of Alfred Edersheim’s The Life and Times of Jesus the Messiah.”11 But this fact, regrettably, did not stop Morey from drawing on Edersheim for support even though his evidence came solely from the Babylonian Talmud. Although Edersheim’s approach comes up short, those (like Dr Head) who make the argument in more recent times arguably have more to answer for. The twentieth century saw an explosion in our understanding of first century Jewish theology, more than anything due to the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls. In one of those titled The Rule of the Community, a reference to the community at Qumran, we read:

The visitation of all those who walk in it [the Spirit of Deceit] (will be) many afflictions by all the angels of punishment, eternal perdition by the fury of God’s vengeful wrath, everlasting terror and endless shame, together with disgrace of annihilation in the fire of the dark region. And all their times for their generations (will be expended) in dreadful suffering and bitter misery in dark abysses until they are destroyed. (There will be) no remnant nor rescue for them.12

Here we have a Jewish community, contemporary with Jesus, who overtly describe final punishment in terms of final annihilation – whatever they might have believed to precede that final fate.

Or again:

The Community Council shall say, all together: “Amen. Amen.” [Blank] And afterwards they shall damn Belial and all his guilty lot. Starting to speak, they shall say: “Accursed be Belial in his hostile plan, and may he be damned in his guilty service. And cursed be all the spirits of his lot in their wicked plan, and may they be damned in their plans of foul impurity. For they are the lot of darkness, and their visitation will lead to the everlasting pit. Amen. Amen. [Blank] And cursed be the wicked … of his rule, and damned be all the sons of Belial in all the iniquities of their office until their annihilation … Amen. Amen. [Blank] And cursed be the angel of the pit and the spirits of destruction in all the designs of your guilty inclination and your wicked counsel. And damned be you in the rule of … and in the dominion … with all … and with the disgrace of destruction without remnant, without forgiveness, by the destructive wrath of God … Amen. Amen.13

Or again, proclaiming God’s judgement on the wicked:

You were created, and your return will be to the eternal pit, for it shall awaken your sin. The dark places will shriek against your pleadings, and all who exist for ever, who seek the truth will arise to judge you. Then all the foolish of heart will be annihilated, and the sons of iniquity will not be found any more.14

One more example:

For all foolish and evil are dark, and all wise and truthful are brilliant. This is why the sons of light will go to the light, to everlasting happiness and to rejoicing; and all the sons of darkness will go to the shades, to death and to annihilation.15