the bible,truth,God's kingdom,JEHOVAH God,New World,JEHOVAH Witnesses,God's church,Christianity,apologetics,spirituality.

Saturday, 7 October 2017

Darwin's "Warm little pond"V. Darwin

Warm Little Pond? PNAS Paper Admits Difficulties Generating RNA on Prebiotic Earth

Evolution News | @DiscoveryCSC

Evolution News | @DiscoveryCSC

A new paper in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences is frank about some of the problems facing the prebiotic synthesis of organics on the early earth. Here’s something amusing from the Abstract:

We find that RNA polymers must have emerged very quickly after the deposition of meteorites (less than a few years).

Really? That sounds amazingly good for origin-of-life research, until you grasp their reasoning:

[T]he rapid losses of nucleobases to pond seepage during wet periods, and to UV photodissociation during dry periods, mean that the synthesis of nucleotides and their polymerization into RNA occurred in just one to a few wet–dry cycles.

In other words, a “warm little pond” (as Darwin quaintly called it) is actually very hostile environments for generating nucleotides. Why? Because within a year or two they’ll (a) lose their nucleotides due to “pond seepage” or (b) dry up, causing nucleotides to photodissaociate. So you must generate them very quickly before one of these terrible things happens and kills your nucleotides.

Since they know that RNA arose naturally, and since the nucleotide constituents of RNA are so fragile in “warm little ponds,” this means that RNA “must have emerged very quickly” in even “less than a few years” on the early earth.

Here’s another admission from the paper, noting that Miller-Urey type chemistry is unlikely to have produced prebiotic organics on the early earth:

As to the sources of nucleobases, early Earth’s atmosphere was likely dominated by CO2, N2, SO2, and H2O. In such a weakly reducing atmosphere, Miller–Urey-type reactions are not very efficient at producing organics. One solution is that the nucleobases were delivered by interplanetary dust particles (IDPs) and meteorites.

Again, they use the same backwards reasoning: They know there was a “warm little pond” and yet the earth’s early atmosphere was not conducive to generating organics. Therefore they came from outside of the earth on “interplanetary dust particles” (IDPs). Only one problem with that hypothesis, as they explain: “nucleobases have not been identified in IDPs”.

But if you could somehow get the nucleotides you then need to link them up into polymers. Hydrothermal vents are another popular hypothesis, except that the paper says they’re a bad place for polymerization:

[E]xperiments simulating the conditions of hydrothermal vents have only succeeded in producing RNA chains a few monomers long. A critical problem for polymerizing long RNA chains near hydrothermal vents is the absence of wet–dry cycles.

Thus, they like warm little ponds (WLPs) for generating organic polymers. But there are more problems to overcome, as they admit:

[T]he buildup of nucleobases in WLPs is offset by losses due to hydrolysis, seepage, and dissociation by UV radiation that was incident on early Earth in the absence of ozone.

They find that seepage is a major problem meaning that “Because of the rapid rate of seepage [~1.0 mm-d.-1 to 5.1 mm-d-1], nucleotide synthesis would need to be fast, occurring within a half-year to a few years after nucleobase deposition.”

Then there’s also a too hot/too cold problem

Nucleotide formation and stability are sensitive to temperature. Phosphorylation of nucleosides in the laboratory is slower at low temperatures, taking a few weeks at 65° C compared with a couple of hours at 100° C. The stability of nucleotides on the other hand, is favored in warm conditions over high temperatures. If a WLP is too hot (>80° C), any newly formed nucleotides within it will hydrolyze in several days to a few years. At temperatures of 5° C to 35° C that either characterize more-temperate latitudes or a postsnowball Earth, nucleotides can survive for thousand-to-million-year timescales. However, at such temperatures, nucleotide formation would be very slow.

In other words, if it’s too hot, then you can generate nucleotides but they degrade quickly. If it’s too cold then they don’t degrade quickly but they are generated too slowly.

They prefer a “hot early Earth (50° C to 80° C) so that sufficient nucleotides build up and “[p]olymerization then occurs in one to a few wet–dry cycles to reduce the likelihood that these molecules are lost to seepage.” But a hot early earth means everything has to happen very quickly.

In other words, because there are so many problems facing the production of RNA, the only way it could have arisen is if it did so quickly that these destructive forces had no time to destroy the RNAs (and the precursor molecules).

Never mind that this paper provides no chemical pathway for forming RNA — under their rapid timescale or any timescale whatsoever. That’s because no such pathway is known to exist.

But why worry? We know the RNA world is true. It all must have happened this way.

For OOL science the show must go on.

Cheaters Never Prosper? Sure They Do in Origin-of-Life Papers

Evolution News | @DiscoveryCSC

Evolution News | @DiscoveryCSC

Today we’re going to look at some recent papers about the origin of life and make some perhaps surprising observations: (1) some of their ideas are demonstrably false, and (2) other ideas cannot possibly be true. Why do the journals let them get away with it? Here’s why: there is no such thing as a sensible materialistic theory for the origin of life, and the one-party rule in science gives them cover. In a world governed by materialism, the only criticisms allowed must also be materialistic. This guarantees absurdity will continue to rule the field.

Fortifying the Soup with a Pinch of Design

Here’s your National Science Foundation at work. Research news from Georgia Tech, thanks to funding from the NSF/NASA Center for Chemical Evolution (paid by taxpayer dollars, in other words), asks: “Was the Primordial Soup a Hearty Pre-Protein Stew?” That one is a gem. Then, mixing his metaphors, reporter Ben Brumfield feeds his hearty stew to the Darwin dancers: “The evolutionary path to first proteins may have been paved with relatively easy, small square-dance steps.”

Hype aside, Brumfield admits that “Scientists have long puzzled over how the very first proteins formed. Their long-chain molecules, polypeptides, can be tough to make in the lab under abiotic conditions.” Previous yields have been modest, he confesses. But now, with assurances from Georgia Tech faculty that they will stick to only realistic early-earth scenarios, he cooks up “pre-protein stew” made of depsipeptides — short chains of amino acids shorter than polypeptides — that he presents as stepping stones to real proteins, provided they get a little help from esters and hydroxy acids, and are submitted to convenient cycles of wetting and drying.

A look at the paper in PNAS shows how they fudged. They started with only left-handed amino acids! This stacked the deck at the outset, without any justification. They also ignored the innumerable damaging cross reactions that would have overwhelmed any useful molecules. Then they skirted around the sequencing problem, even though the paper makes it clear they are fully aware of the fact that sequence space vastly exceeds usable protein space, as Doug Axe has made clear in his papers (referenced in his book, Undeniable).

One of the most daunting challenges associated with this question is the inherent vastness of proto-peptide sequence space, which may be many orders of magnitude greater than that of peptides encoded by genes in living cells. If a model prebiotic pool of only 10 amino acids and 10 hydroxy acids is considered, and equal monomer reactivity is assumed, the potential number of depsipeptide sequences with length 10 would be (10 + 10)10, or ∼1013. As a result of this staggering number, progress on the characterization of plausibly prebiotic amino acid pools, abiotic mechanisms for peptide self-assembly, and the evolution of early ribosomes has not been paralleled by a systems-level understanding of proto-peptide diversity.

But rather than buckle under that fact, they decided to play with sequences of four amino acids. That’s right: four. Knowing that the problem mushrooms the longer the sequence, they extrapolated their hope far beyond just four peptides (tetramers).

The observation of more diverse tetramers as the system evolved is consistent with the hypothesis that a vast array of sequences may have been present on the prebiotic earth before the initiation of template-directed peptide synthesis.

Did they find that unguided natural laws honed in on the tiny subset of useful sequences? No. They just assumed that the more random sequences, the better. Does that make any sense? Do more haystacks produce more needles? Even if they did, will the needles get together on an earth-sized soup? Will a part in a pond in Africa find its matching part in South America? Will matching parts be produced at the same time? For polypeptides long enough to have biotic significance, it would be outrageous to think so. Both William Dembski and Doug Axe have treated navigating sequence space as a search algorithm. Without intelligent design in the form of an independently supplied treasure map, no evolutionary algorithm is superior to blind search. This implies that tetramers have no better way of locating a useful protein sequence than does pure chance. (For that improbability, see Illustra’s amoeba illustration from the film Origin.)

Consider their sentence, “a vast array of sequences may have been present on the prebiotic earth before the initiation of template-directed peptide synthesis.” Whoa! Stop right there! What is “the initiation of template-directed peptide synthesis”? Where did that come from? They’re talking about genetic codes! Transcription machinery! Transfer RNAs! Messenger RNAs! Ribosomes! Words fail to describe the hurdles those things present for naturalism. The researchers know this, but evidently didn’t complain when their university’s press office put out misleading metaphors about “hearty pre-protein stew” and how “The evolutionary path to first proteins may have been paved with relatively easy, small square-dance steps.”

Boring Boron

Let’s take a brief look at another example of fudging by federally funded labs doing origin-of-life research. “Discovery of boron on Mars adds to evidence for habitability,” promises the Los Alamos National Laboratory. In this case, instead of proteins, they’re trying to build RNA or DNA, which use complex sugars.

The subtitle reads, “Boron compounds play role in stabilizing sugars needed to make RNA, a key to life.” Strange as it seems, the Curiosity rover found a chemical element on the red planet. Who would have thought? Life must be coming right up in the Mars kitchen! The hopeful headline conceals the desperation origin-of-life chemists have suffered trying to get ribose to form and survive under plausible prebiotic conditions.

RNA (ribonucleic acid) is a nucleic acid present in all modern life, but scientists have long hypothesized an “RNA World,” where the first proto-life was made of individual RNA strands that both contained genetic information and could copy itself. A key ingredient of RNA is a sugar called ribose. But sugars are notoriously unstable; they decompose quickly in water. The ribose would need another element there to stabilize it. That’s where boron comes in. When boron is dissolved in water — becoming borate — it will react with the ribose and stabilize it for long enough to make RNA.

The research is published (open-access) in Geophysical Research Letters. Like the first paper, this “scenario” relies on wet-dry cycles to work magic. But since they don’t even consider how peptides could have formed, there’s an even greater time and distance problem here. Granting them the most inconceivably generous latitude to assume that ribose did form, and then RNA, and then DNA, how would they get those parts to earth to work on the peptides? Or how would the proteins get to Mars? It’s ridiculous to think that Mars “may” have been habitable just because the rover found some boron in Gale Crater.

On Mars, we have shown borate was present in a long-lived hydrologic system, suggesting that important prebiotic chemical reactions could plausibly have occurred in the groundwater, if organics were also available. Thus, the discovery of boron in Gale crater opens up intriguing questions about whether life could have arisen on Mars.

We couldn’t find any units, definitions, or numbers on their “plausibility” scale. Many of the same hurdles exist in this scenario. How did unguided causes select only one-handed sugars? How did the bases, even if they formed, arrange themselves into the tiny fraction of functional sequences out of an extremely vast sequence space? How did they become associated with polypeptides, such that protein machines “took over” the transcription and translation function? The conceptual and experimental difficulties glossed over in these two papers are numerous, egregious, and insurmountable.

The two papers remind one of the joke about a hobo cheering up his hungry buddy, saying, “If we had ham, we could have ham and eggs, if we had eggs.” The buddy’s hunger will not be satisfied if the friend promises, “I might be able to get some ham (or eggs).” “Really? Got any?” “Not yet, but I’m working on a scenario to get some.” “Like what?” “Well, I figure if I put these pebbles in a puddle and let them get wet and dry over a few years, I imagine that some building blocks of pre-ham or pre-eggs might emerge someday.”

Onward but Not Upward

One more example. Again, in PNAS, with government support from the U.S. Department of Energy, researchers assume the myth of progress. Simple things will climb the ladder to elegant systems, won’t they? This paper presents the “Foldamer hypothesis for the growth and sequence differentiation of prebiotic polymers.” Basically, they try to leapfrog over the sequence-space hurdle with little steps. Notice their trust in the myth of progress:

Today’s lifeforms are based on informational polymers, namely proteins and nucleic acids. It is thought that simple chemical processes on the early earth could have polymerized monomer units into short random sequences. It is not clear, however, what physical process could have led to the next level — to longer chains having particular sequences that could increase their own concentrations. We study polymers of hydrophobic and polar monomers, such as today’s proteins. We find that even some random sequence short chains can collapse into compact structures in water, with hydrophobic surfaces that can act as primitive catalysts, and that these could elongate other chains. This mechanism explains how random chemical polymerizations could have given rise to longer sequence-dependent protein-like catalytic polymers.

These researchers, too, know that “sequence spaces grow exponentially with chain length,” leading to the admission that, “Therefore, those few particular special sequences would wash out as biology moves into an increasingly larger sequence space sea.” To overcome this hurdle, they appeal to imagination, supposing that little folds will accumulate into the large, complex folds we see in real proteins.

Our goal here has not been to consider the evolution of functionalities beyond “ribosome-like chain elongation,” but ensemble models, such as this one, would lead to many other potential functionalities.

Real functionalities? No; “potential functionalities.” Their model “aims to capture a few principles in a coarse-grained way,” held together by copious amounts of imagination and faith.

Even so, the sorts of actions suggested here are currently more in the realm of speculation than proven fact. Below, we describe results of computer simulations that lead to the conclusion that short random HP chains carry within them the capacity to autocatalytically become longer and more protein-like.

What they don’t realize, though, is that there’s no free lunch. The “No Free Lunch” theorems that Dembski explicates in his book of that name guarantee that no search algorithm (such as their foldamer hypothesis) is superior to blind search. Without intelligence, there’s no way to improve on sheer dumb luck.

Conclusions

When we point out the flaws in materialistic scenarios like this, a common response is that we must be resorting to god-of-the-gaps. Isn’t lab research better than sitting back and saying, “God did it” whenever we encounter a problem?

Actually, the shoe is on the other foot. We have good reason to embrace the alternative, intelligent design. Whenever we find complex systems of functional, hierarchical, coded information where we have the opportunity to observe the system come into existence, we always find intelligence as the source. The Law of Uniformity justifies our approach in considering intelligence as the vera causa of the systems in life, which dramatically exceed in purposeful complexity anything humans have ever designed. Intelligence is a cause we know. It is necessary. It is sufficient. The rational response is to appeal to intelligent causes, not to arbitrarily rule them out a priori.

By contrast, working against the known laws of chemistry and probability in order to maintain a philosophical preference is anti-scientific. The only way to claim progress is to play games, as these three instances show: speculating, imagining, and hyping. In essence, they commit materialism-of-the-gaps to bridge huge chasms that keep growing wider with each new discovery about the complexity of life.

On the randomness of Darwinism.

Is evolution random? Answering a common challenge

By Ann Gauger

Evolutionists often challenge us for referring to Darwinian evolution as “random.” They point to the fact that natural selection, the force that supposedly drives the train, always selects more “fit” organisms, and so is not random. That is only part of the story, though, and to understand why evolution can indeed be called random, the rest needs to be told.

Evolution can be considered to be composed of four parts. The first part, the grist for the mill, is the process by which mutations are generated. Generally this is thought to be a random process, with some qualifications. Single base changes occur more or less randomly, but there is some skewing as to which bases are substituted for which. Other kinds of mutations, like deletions or rearrangements or recombinations (where DNA is exchanged between chromosomes), often occur in hotspots, but not always. The net effect is that mutations occur without regard for what the organism requires, but higgledy-piggledy. In that sense mutation is random

The next part, random drift, is like a roll of the dice that decides which changes are preserved and which are lost. As the name implies, this process is also random, the result of accidental events, and without regard for the benefit of the organism. Most mutations get lost in the mix, especially when newly emerging, just because their host organisms fail to reproduce, or die from causes unrelated to genetics. It can also happen that new mutations are combined with other mutations that are harmful, and so get eliminated.

The random effects of drift are large enough to overwhelm natural selection in organisms with small breeding populations, less than a million, say. New mutations are not born fast enough to escape loss due to drift. There is a fractional threshold in the population that must be crossed before a new mutation can become “fixed,” that is, universally present in every individual. A new mutation generally is lost to drift before that population threshold is crossed.

The third part, natural selection, is not random. It acts to preserve beneficial change and eliminate harmful ones. It can be said to be directional. But there are several caveats. Beneficial mutations are rare, and usually only weakly beneficial, so the effects of natural selection are not usually all that strong. Most changes provide only a slight advantage.

In addition, it can happen, and often does, that a “beneficial” mutation involves breaking something, meaning a loss of information, and a loss of potential improvement. This breaking can be irreversible for all intents and purposes. The premiere example in human evolution is that of sickle cell disease. Sickle cell disease is caused by a mutation to the hemoglobin gene that makes red blood cells resistant to the malarial parasite. In one copy the broken gene is beneficial (it increases resistance to malaria), but when two copies are present (both chromosomes carry the mutation), the red blood cells are deformed and cause painful debilitation. The broken gene is actually functionally worse than its normal version, except where malaria is present.

This brings out an important point. Natural selection does not always select the same mutations. The environment determines which mutations are favored. For example, natural selection acts to favor individuals carrying one copy of the sickle cell trait where malaria is present, but acts against the sickle cell gene where malaria is absent. So in this context, selection meanders over a fluctuating landscape of varying criteria for what is beneficial and what is not. Now it is beneficial to carry the sickle cell trait, now it is not. Different populations get favored at different times. In this sense one might say selection has a random component too, because only rarely is selection strong and unidirectional, always favoring the same mutation.

We see this variation in selection with another example, the evolution of finch beaks on the Galápagos Islands. In drought, large beaks are favored, in wet years, small beaks. The weather fluctuates, and so do the beak sizes.

Subpopulations may acquire traits, but because of environmental variation the traits do not become universal. For example, lactose intolerance – we do not all carry the version of the gene that allows us to digest lactose as adults. Unless suddenly everyone in the world has to eat cheese as a major part of their diet, lactose intolerance won’t disappear from our population.

There is a special way evolution can occur – a sudden bottleneck in the population will tend to fix the traits that predominate in that population. Suppose a nuclear holocaust wiped out everyone except Swedes. The lactose-digesting gene would almost certainly become fixed, as would blond hair, blue eyes, and other Scandinavian traits, provided they ate cheese and lived at high latitudes. Until new mutations in new environments occurred, that would remain the case.

Now you know more about the population genetics of evolution than you imagined could be true. The sum of all these factors is what is responsible for evolution, or change over time. Mutation, drift, selection, and environmental change all play a role. Three out of these four forces are random, without regard for the needs of the organism. Even selection can be random in its direction, depending on the environment.

So tell me. Is evolution random? Most of the processes at work definitely are. Certainly evolution won’t make steady progress in one direction without some other factor at work. What that factor might be remains to be seen. I personally do not think a material explanation will be found, because any process to guide evolution in a purposeful way will require a purposeful designer to create it.

By Ann Gauger

Evolutionists often challenge us for referring to Darwinian evolution as “random.” They point to the fact that natural selection, the force that supposedly drives the train, always selects more “fit” organisms, and so is not random. That is only part of the story, though, and to understand why evolution can indeed be called random, the rest needs to be told.

Evolution can be considered to be composed of four parts. The first part, the grist for the mill, is the process by which mutations are generated. Generally this is thought to be a random process, with some qualifications. Single base changes occur more or less randomly, but there is some skewing as to which bases are substituted for which. Other kinds of mutations, like deletions or rearrangements or recombinations (where DNA is exchanged between chromosomes), often occur in hotspots, but not always. The net effect is that mutations occur without regard for what the organism requires, but higgledy-piggledy. In that sense mutation is random

The next part, random drift, is like a roll of the dice that decides which changes are preserved and which are lost. As the name implies, this process is also random, the result of accidental events, and without regard for the benefit of the organism. Most mutations get lost in the mix, especially when newly emerging, just because their host organisms fail to reproduce, or die from causes unrelated to genetics. It can also happen that new mutations are combined with other mutations that are harmful, and so get eliminated.

The random effects of drift are large enough to overwhelm natural selection in organisms with small breeding populations, less than a million, say. New mutations are not born fast enough to escape loss due to drift. There is a fractional threshold in the population that must be crossed before a new mutation can become “fixed,” that is, universally present in every individual. A new mutation generally is lost to drift before that population threshold is crossed.

The third part, natural selection, is not random. It acts to preserve beneficial change and eliminate harmful ones. It can be said to be directional. But there are several caveats. Beneficial mutations are rare, and usually only weakly beneficial, so the effects of natural selection are not usually all that strong. Most changes provide only a slight advantage.

In addition, it can happen, and often does, that a “beneficial” mutation involves breaking something, meaning a loss of information, and a loss of potential improvement. This breaking can be irreversible for all intents and purposes. The premiere example in human evolution is that of sickle cell disease. Sickle cell disease is caused by a mutation to the hemoglobin gene that makes red blood cells resistant to the malarial parasite. In one copy the broken gene is beneficial (it increases resistance to malaria), but when two copies are present (both chromosomes carry the mutation), the red blood cells are deformed and cause painful debilitation. The broken gene is actually functionally worse than its normal version, except where malaria is present.

This brings out an important point. Natural selection does not always select the same mutations. The environment determines which mutations are favored. For example, natural selection acts to favor individuals carrying one copy of the sickle cell trait where malaria is present, but acts against the sickle cell gene where malaria is absent. So in this context, selection meanders over a fluctuating landscape of varying criteria for what is beneficial and what is not. Now it is beneficial to carry the sickle cell trait, now it is not. Different populations get favored at different times. In this sense one might say selection has a random component too, because only rarely is selection strong and unidirectional, always favoring the same mutation.

We see this variation in selection with another example, the evolution of finch beaks on the Galápagos Islands. In drought, large beaks are favored, in wet years, small beaks. The weather fluctuates, and so do the beak sizes.

Subpopulations may acquire traits, but because of environmental variation the traits do not become universal. For example, lactose intolerance – we do not all carry the version of the gene that allows us to digest lactose as adults. Unless suddenly everyone in the world has to eat cheese as a major part of their diet, lactose intolerance won’t disappear from our population.

There is a special way evolution can occur – a sudden bottleneck in the population will tend to fix the traits that predominate in that population. Suppose a nuclear holocaust wiped out everyone except Swedes. The lactose-digesting gene would almost certainly become fixed, as would blond hair, blue eyes, and other Scandinavian traits, provided they ate cheese and lived at high latitudes. Until new mutations in new environments occurred, that would remain the case.

Now you know more about the population genetics of evolution than you imagined could be true. The sum of all these factors is what is responsible for evolution, or change over time. Mutation, drift, selection, and environmental change all play a role. Three out of these four forces are random, without regard for the needs of the organism. Even selection can be random in its direction, depending on the environment.

So tell me. Is evolution random? Most of the processes at work definitely are. Certainly evolution won’t make steady progress in one direction without some other factor at work. What that factor might be remains to be seen. I personally do not think a material explanation will be found, because any process to guide evolution in a purposeful way will require a purposeful designer to create it.

Sunday, 1 October 2017

Mission creep?

Cosmologist Sean Carroll asks, Is anything constant?

November 28, 2015 Posted by News under Cosmology, Physics

From PBS:

The ability for seemingly constant things to evolve and change is an important aspect of Einstein’s legacy. If space and time can change, little else is sacred. Modern cosmologists like to contemplate an extreme version of this idea: a multiverse in which the very laws of physics themselves can change from place to place and time to time. Such changes, if they do in fact exist, wouldn’t be arbitrary; like spacetime in general relativity, they would obey very specific equations.

So are we now enlisting Einstein on behalf of the multiverse? Out of interest, what would he have thought?

We currently have no direct evidence that there is a multiverse, of course. But the possibility is very much in the spirit of Einstein’s reformulation of spacetime, or, for that matter, Copernicus’s new theory of the Solar System. Our universe isn’t built on unmovable foundations; it changes with time, and discovering how those changes occur is an exciting challenge for modern physics and cosmology. More.

Physicist Rob Sheldon responds,

We’ve dissected Sean “the cosmologist” Carroll before, who is willing to sacrifice cosmology to the altar of Darwin, promoting “evolution” of “multiverses”. In this article he is equivocating on the word “change” to suggest that if Einstein showed that spacetime was changeable, then evolution must be true. I would argue that it merely demonstrates Cosmology to be in smaller denominations than the other bills of truth in circulation.

Seriously, though, attempting make Evolution the “one thing that is constant” in a changing world, reverses the usual hierarchy of “biology being made out of the laws of physics”, replacing it with “physics being made out of the laws of biology”. Now I’ve read Rosen’s “Essays on Life Itself”, so I won’t say that life is “nothing but” complicated physics, yet surely it would be equally incorrect to adopt Sean’s view that cosmology is “nothing but” evolution of physical constants.

Yet this is a perfect illustration of the dualist tension that swings between extremes. Newton’s deterministic, clock-like universe had fixed laws, fixed mechanisms, fixed purpose, fixed boundary conditions, while Carroll’s evolutionary, biological universe has changing laws, changing mechanisms, changing (if even existing) purpose, changing boundary conditions. The miracle of science, however, stands between the extremes.

November 28, 2015 Posted by News under Cosmology, Physics

From PBS:

The ability for seemingly constant things to evolve and change is an important aspect of Einstein’s legacy. If space and time can change, little else is sacred. Modern cosmologists like to contemplate an extreme version of this idea: a multiverse in which the very laws of physics themselves can change from place to place and time to time. Such changes, if they do in fact exist, wouldn’t be arbitrary; like spacetime in general relativity, they would obey very specific equations.

So are we now enlisting Einstein on behalf of the multiverse? Out of interest, what would he have thought?

We currently have no direct evidence that there is a multiverse, of course. But the possibility is very much in the spirit of Einstein’s reformulation of spacetime, or, for that matter, Copernicus’s new theory of the Solar System. Our universe isn’t built on unmovable foundations; it changes with time, and discovering how those changes occur is an exciting challenge for modern physics and cosmology. More.

Physicist Rob Sheldon responds,

We’ve dissected Sean “the cosmologist” Carroll before, who is willing to sacrifice cosmology to the altar of Darwin, promoting “evolution” of “multiverses”. In this article he is equivocating on the word “change” to suggest that if Einstein showed that spacetime was changeable, then evolution must be true. I would argue that it merely demonstrates Cosmology to be in smaller denominations than the other bills of truth in circulation.

Seriously, though, attempting make Evolution the “one thing that is constant” in a changing world, reverses the usual hierarchy of “biology being made out of the laws of physics”, replacing it with “physics being made out of the laws of biology”. Now I’ve read Rosen’s “Essays on Life Itself”, so I won’t say that life is “nothing but” complicated physics, yet surely it would be equally incorrect to adopt Sean’s view that cosmology is “nothing but” evolution of physical constants.

Yet this is a perfect illustration of the dualist tension that swings between extremes. Newton’s deterministic, clock-like universe had fixed laws, fixed mechanisms, fixed purpose, fixed boundary conditions, while Carroll’s evolutionary, biological universe has changing laws, changing mechanisms, changing (if even existing) purpose, changing boundary conditions. The miracle of science, however, stands between the extremes.

In South Korea a just resolution to the issue of conscientious objection closer?

Groundswell of Recognition of Right to Conscientious Objection in South Korea

A social consensus has continued to grow in South Korea since the July 2015 public hearing of its Constitutional Court. Even in the absence of the Court’s decision or new legislation, South Korea is progressing in its view of conscientious objection to military service. The opinions of lower courts, the public, the legal community, and the national and international human rights communities support a solution that does not punish the exercise of freedom of conscience.

Unprecedented Shift in Opinions of the Courts

During the week of August 7, 2017, seven young men standing trial for their conscientious objection to military service received not-guilty decisions. This development is unprecedented. In the Republic of Korea’s legal history, courts have convicted more than 19,000 conscientious objectors, but 38 of the 42 not-guilty decisions ever rendered on this issue have come since May 2015, with 25 already in 2017.

Some courts have deferred the cases in hopes of receiving the Constitutional Court’s ruling, causing the number of pending cases on the issue to grow. Mr. Du-jin Oh, a lawyer who has represented many conscientious objectors, observed that there are now more than five times as many pending cases on the issue as compared with just a few years ago.

Many observers see a shift in the thinking of South Korea’s judiciary. In rendering the not-guilty decisions, many courts noted that punishing conscientious objectors in the absence of an alternative civilian service program is a violation of the constitution’s guarantee of freedom of conscience. Others have determined that conscientious objection to military service is a “justifiable ground” for refusing military call-up, as provided for in the Military Service Act.

Public Opinion

While public opinion is not the determining factor in recognizing and protecting human rights, the Ministry of Defense has used the lack of popular support to justify its refusal to resolve this issue. But public opinion is changing. In 2005, only 10 percent of those surveyed agreed with the idea of recognizing the right of conscientious objection. However, a May 2016 poll reported that 70 percent of participants supported the further step of implementing alternative service. A July 2016 poll of the Seoul Bar Association showed that more than 80 percent supported it.

Opinions and Decisions of the Human Rights Community

The National Human Rights Commission of Korea (NHRC) saw that the changing viewpoints in South Korea had prompted legislators to propose adopting alternative service in three different amendment bills to the National Assembly for its session starting June 2017. The NHRC also took note of opinions and decisions from the international community urging this action and then examined how the proposals measured up to international standards for alternative civilian service. The NHRC provided the government of South Korea with its conclusions on an alternative civilian service program that adheres to international standards and that has been acceptable to Jehovah’s Witnesses and others.

A Promise and a Petition

When President Jae-in Moon was inaugurated on May 10, 2017, he brought to that office both his experience as a human rights lawyer and a promise: “Freedom of conscience is a fundamental right of the highest level among all fundamental rights under the Constitution. Therefore, I promise to implement alternative service and get rid of the current practice of imprisoning conscientious objectors.”

On August 11, 2017, a delegation representing 904 conscientious objectors submitted a petition to the new president, asking that the government recognize the right to conscientious objection by releasing those imprisoned and implementing an alternative civilian service program. The petitioners are comprised of 360 conscientious objectors serving a prison term and 544 under trial at various levels of court at the time of their petition.

An Opportunity to Make an Enduring Mark in the History of Human Rights

Hyun-soo Kim, one of the petitioners, commented on what the petition means to him: “I am looking forward to the adoption of alternative service that harmonizes with international standards, a purely civilian alternative service that is not connected to or supervised by the military. I am willing to serve in areas of social welfare or disaster relief or in whatever areas I might be assigned. It would be rewarding to contribute to the community.”

Jehovah’s Witnesses and others are happy to see the shift in opinions that may help prompt change of a policy that has punished thousands of men over the course of seven decades. The Witnesses are grateful that President Moon, members of the National Assembly, and South Korea’s judiciary have shown a genuine interest in respecting and accommodating those who conscientiously object to military service.

Darwinism v.The human body.

Dr. Howard Glicksman Describes Intricate Control Systems Sustaining Your Life Right Now

Evolution News | @DiscoveryCSC

On a new episode of ID the Future, biologist Ray Bohlin interviews physician Howard Glicksman about a common cause of death, cardio-pulmonary arrest. They use the subject as a doorway to explore some intricate, interdependent control systems that sustains life. Listen to the podcast here.

Evolution News | @DiscoveryCSC

On a new episode of ID the Future, biologist Ray Bohlin interviews physician Howard Glicksman about a common cause of death, cardio-pulmonary arrest. They use the subject as a doorway to explore some intricate, interdependent control systems that sustains life. Listen to the podcast here.

Saturday, 30 September 2017

File under "Well said" LIV

Dignify and glorify common labor. It is at the bottom of life that we must begin, not at the top. Booker T. Washington

And still yet more iconoclasm.

Darwin’s Point: No Evidence for Common Ancestry of Humans with Monkeys

Günter Bechly

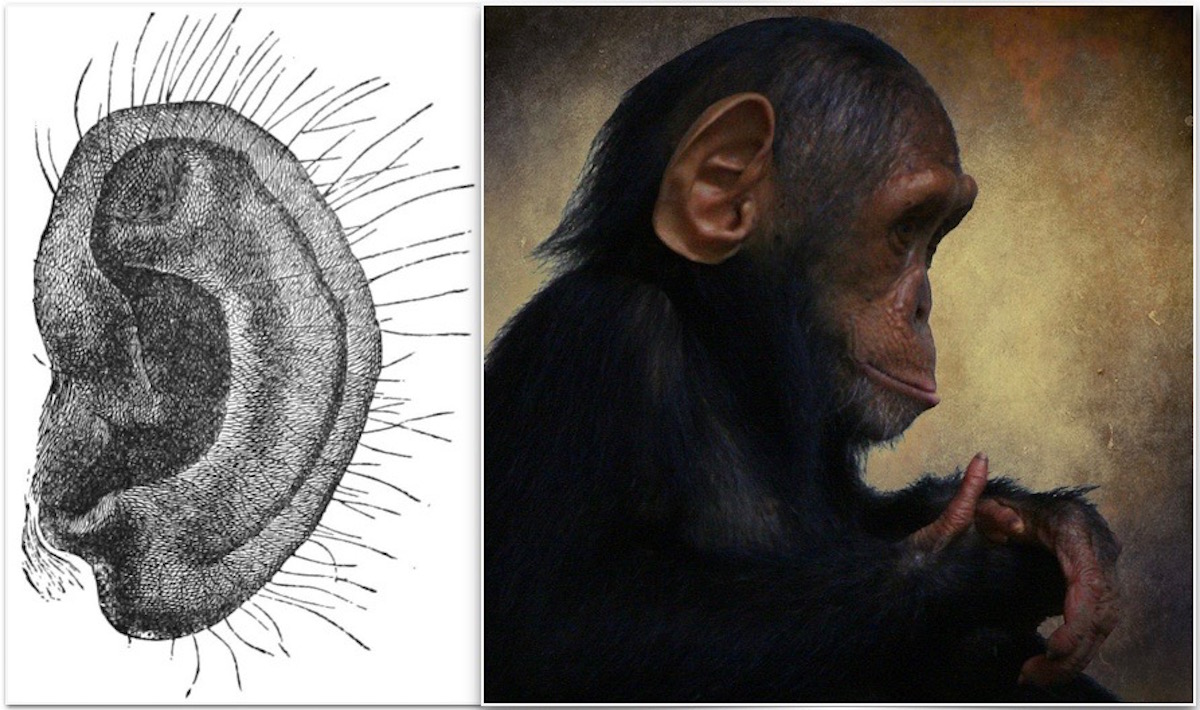

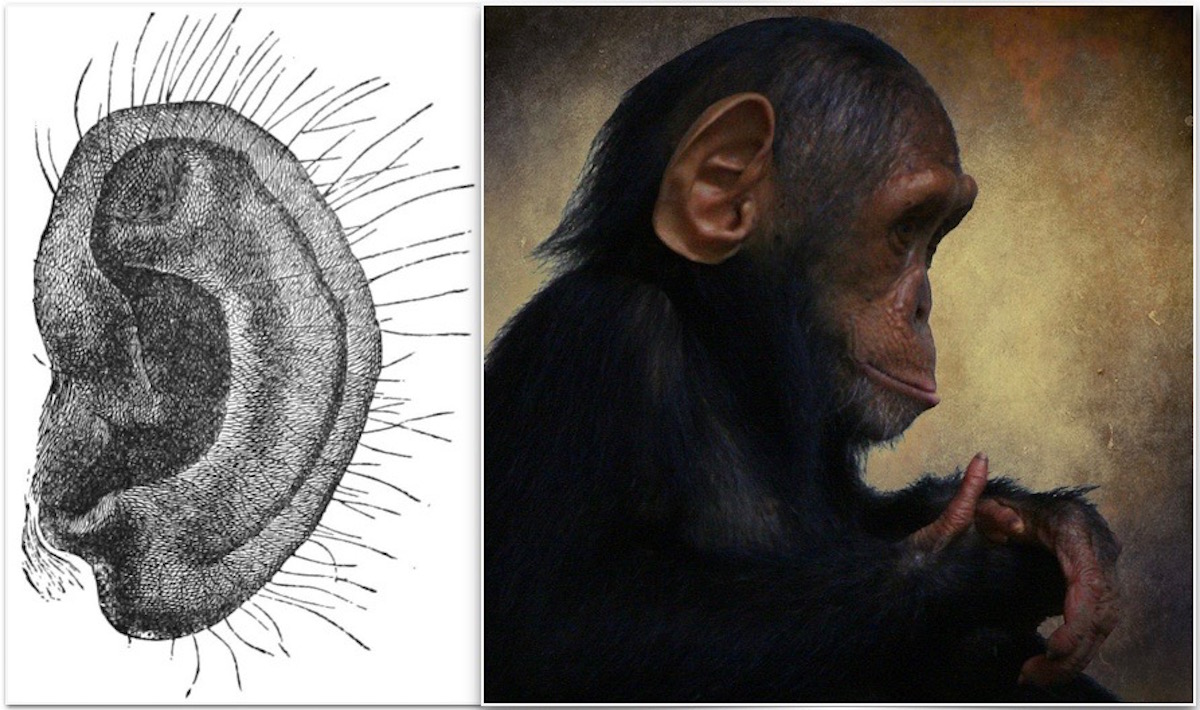

In a recent post for Evolution News, we discussed vestigial structures as alleged evidence for evolution ((Chaffee 2017). As an illustration, the article featured an image of the auricular tubercles or “Darwin’s ear points,” a bump-like thickening on the helix of the auricle (exterior ear) of many people that is often claimed to be an atavistic vestige of the pointy ear tip found in monkeys. Evolutionists say the feature proves a shared ancestry of humans with lower primates.

The bump was originally discovered by the celebrated British sculptor Thomas Woolner, who informed Charles Darwin about it. In Darwin (1871:15-17) cited this structure as probable evidence for common ancestry of humans and monkeys. However, at the same time there were already published doubts about this interpretation (Meyer 1871), mainly because of the variability in humans.

Nevertheless, the claim that Darwin’s tubercle is an atavistic structure is still often heard today. Martin Nickels (1998), an anthropologist at Illinois State University, presented Darwin’s tubercle among his “Twelve Lines of Evidence for the Evolution of Humans & Other Primates,” which was featured at the Talk Origins website and published in the 1998 Creation-Evolution issue of the Reports of the National Center for Science Education. In the Wikipedia articles on “Vestigiality” and “Human Vestigiality,” the tubercle is mentioned as one example of vestigial structures. Many popular blogs list this feature as strong evidence for human evolution. Here are two examples:

In“WEIT: Human Vestigiality & Atavisms” (March 19, 2011), on the atheist blog Reflections from the Other Side: Leaving Christianity and Embracing Skepticism, the author refers to Jerry Coyne’s book Why Evolution Is True:

I want to add one atavistic feature that Coyne doesn’t mention: a tiny, almost imperceptible point on the outer rim of the ear known as Darwin’s tubercle.Only 10% of the population has it, but I’m lucky enough to be part of that statistic. Darwin’s tubercle demonstrates our common ancestry with other primates, which have significantly more prominent pointed ears, possibly to help funnel sound into the auditory canal. Below is my ear, a macaque’s ear and an example illustration from Darwin’s The Descent of Man.

It’s both startling and fascinating to realize that I carry tangible, visible evidence for evolution with me wherever I go. And by no means is this connection to the past is something to be ashamed of. On the contrary, to bear such tokens of our history just serves as a reminder of how far our species has come.

In “I Have Primitive Ears” (April 28, 2012), on the blog Rosa Rubicondior: Religion, science and politics from a centre-left atheist humanist. The blog religious frauds tell lies about, another writer observes;

I’m not one to boast, but I have primitive ears. I have the sort of ears of which my remote ancestors might have been proud, if they had had the cognitive ability to be proud.

I have Darwin’s Tubercles … It is a vestige of the ear point found in many simians and, presumably, in our common ancestors.

These are pretty strong claims, from the usual suspects. Yet there are two problems that show Darwin’s tubercles represent an example of evolutionary myth-making.

The first problem, a minor one, concerns a failed prediction. If Darwin’s tubercle were a homologue and an atavistic remnant of the pointy ears of monkeys, we should expect to find this structure in other apes, too, and especially in chimpanzees. The latter, of course, are claimed to be our closest relatives, and have rounded exterior ears similar to humans. According to personal information from British zoologist Edwin Ray Lankester, Darwin (1871:15) briefly mentioned that a chimp from the Zoological Garden at Hamburg did possess this feature. Of course, such dubious hearsay does not qualify as scientific evidence. Indeed, in their recent comprehensive literature review about Darwins’s tubercle, Loh & Cohen (2016) did not mention any record from apes. Likewise, I could not find any descriptions or images anywhere in literature or online that document a chimp ear with a Darwin’s tubercle. All available images of chimp ears do not show anything like a Darwin’s tubercle. So the evolutionary prediction seems to be refuted or at least highly dubious, at least until proven otherwise.

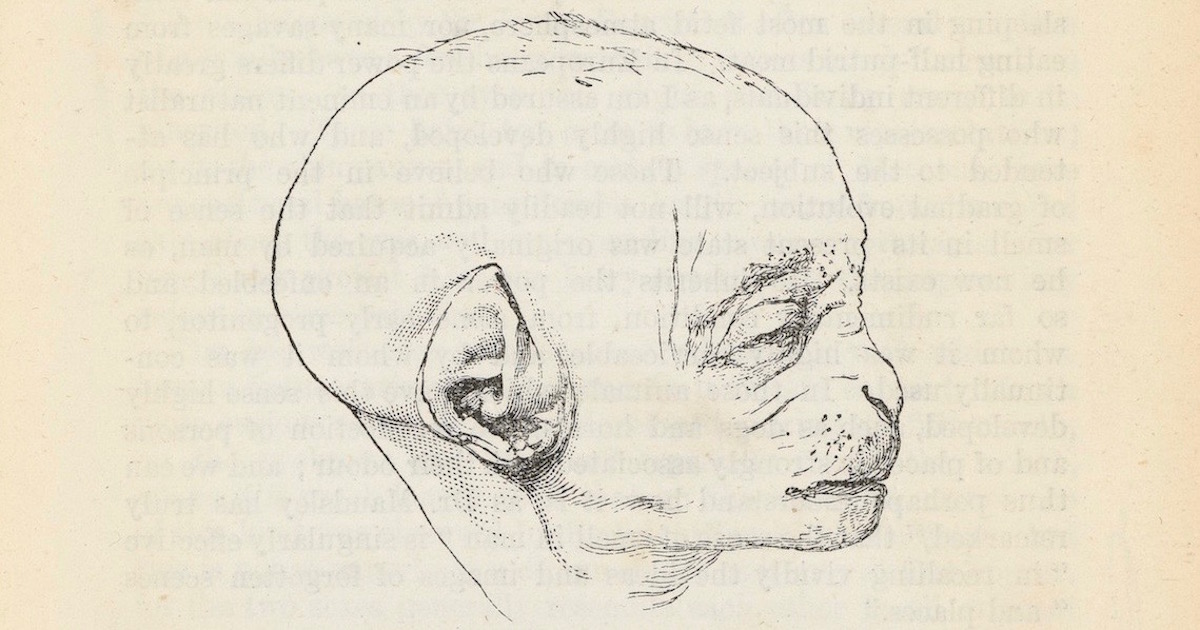

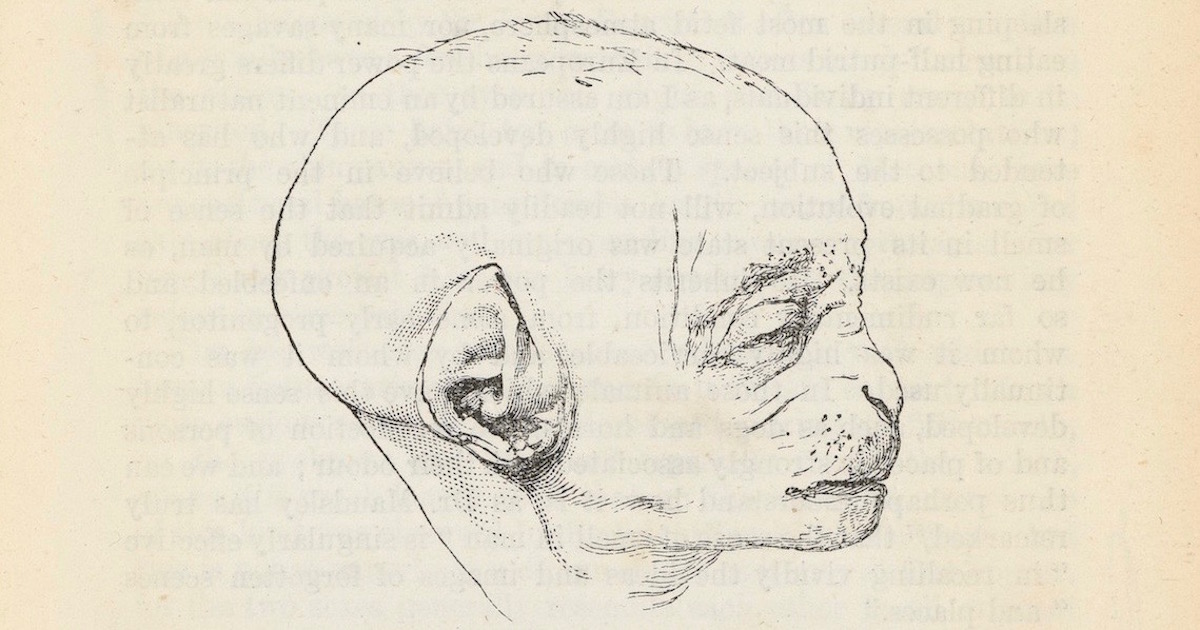

Darwin, in his fervor to present evidence for evolution, cannot always be trusted. This is also shown by the case of his figure (Darwin 1871: fig. 3) of an alleged orangutan fetus featuring a pointy ear unlike that of adult apes. Darwin considered this a kind of ontogenetic recapitulation of evolution. However, the claim is simply false, as Ankel-Simons (2010: 433) mentions:

Schultz (1965, 1969) states that the pointed ear of an “orangutan foetus” that was pictured and described by Darwin (1871) was caused by a deformation of that particular fetus, which Schultz was able to inspect. … Moreover, in Schultz’s judgment, the particular fetus is that of a gibbon and not of an orangutan.

The second problem is much more damaging to the atavism hypothesis. Pointed ear tips are a feature in many monkey species. It is present in all members of the concerned species and always symmetrically present on both ears in both sexes. This strongly suggests that the structure is genetically based and inherited. However, in humans, the feature shows great variability and occurs, for example, in only 10 percent of Spanish adults, 40 percent of Indian adults, and 58 percent of Swedish school children. Some people only have this tubercle on one ear. In half of the pairs of identical twins that were studied, only one of the twins had the ear bumps (Quelprud 1936).

Because of this evidence, and based as well on two genetic studies, McDonald (2011) concluded in an article about what he called the “myth” of Darwin’s tubercle:

The family and twin studies strongly indicate that Darwin’s tubercle is not determined by a single gene with two alleles, and there may be very little genetic influence on the trait at all. You should not use Darwin’s tubercle to demonstrate basic genetics.

But if these ear bumps have no genetic cause, but instead represent environmentally induced developmental accidents, they simply cannot be considered atavistic structures. There is no proof here of common ancestry of humans and monkeys!

Ankel-Simons (2010: 433) thus writes in his standard textbook on Primate Anatomy:

This point of the ear auricle has gone into natural history lore as “tuberculum Darwini” or “Darwin’s point.” It is still regarded by many as an atavism in humans, where the point is actually rarely found. Many human anatomy texts compare the “auricular tubercle of Darwin” with the pointed ears of “adult monkeys.” Lasinsky, however, shows that the two structures have nothing in common. The auricular tubercle of Darwin has had a rather exaggerated revival in the very pointed ears of alien “Vulcans” who evolved from the fantasy of the creators of Star Trek and Star Trek: The Next Generation.

So we can safely conclude that Darwin’s tubercle must be added to the ever-growing list of what Jonathan Wells calls Icons of Evolution (Wells 2000). Rather than modern science, they are debunked science fiction. But as Wells (2017) has also shown, such Zombie Science is hard to kill. It always creeps back from some dark corner of the Internet.

Yet we should add that there is a much more fundamental problem weighing against vestigiality as evidence for evolution and common ancestry.

Critics of evolution often refer to the discovery of function for allegedly vestigial organs, such as the human appendix, tonsils, and coccyx, or the tiny pelvic bones in whales (Klinghoffer 2014). The critics argue that such “vestigial” organs are equally compatible with the design hypothesis. Evolutionists, meanwhile, usually respond by emphasizing that vestigiality does not imply absence of any function. Instead, it is commonly defined as “the retention during the process of evolution of genetically determined structures or attributes that have lost some or all of their ancestral function in a given species” (Wikipedia,“Vestigiality” ).

However, if the total or partial absence of function is restricted only to an assumed ancestral function, then common ancestry is itself assumed in the definition of the concept of vestigiality. The result is that vestigiality cannot be used as evidence for common ancestry without committing the logical fallacy of begging the question, or circular reasoning.

Alternatively, some evolutionists say that in vestigial organs, homology and not functionality is the crucial issue. However, this creates the same problem, on a different level. Just like vestigiality, the concept of homology presupposes common ancestry and therefore cannot be used to prove it. (See Wikipedia, “Homology”: “In biology, homology is the existence of shared ancestry between a pair of structures, or genes, in different taxa.”) The presumption of common ancestry is not optional for homology, because without the notion of common ancestry one could not distinguish homologous similarities from convergent similarities.

Consequently, large parts of the allegedly strongest evidence for evolution from comparative morphology indeed are invalid and based on logically fallacious reasoning.

Literature:

Ankel-Simons F 2010. Primate Anatomy: An Introduction. Academic Press, Cambridge, 752 pp.

Chaffee S 2017. “Theology in Biology Class: Vestigial Structures as Evidence for Evolution.” Evolution News, September 21, 2017.

Darwin C 1871. Chap. I. Rudiments. p. 15 in: The Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex. John Murray, London.

Klinghoffer D 2014. “Now It’s Whale Hips: Another Icon of Darwinian Evolution, Vestigial Structures, Takes a Hit.” Evolution News, September 15, 2014.

Lasinsky W 1960. Äußeres Ohr. pp. 41–74 in: Hofer HO, Schultz AH, Starck D (eds). Primatologia, Handbook of Primatology Vol. II. Karger, Basel.

Loh TY, Cohen PR 2016. “Darwin’s Tubercle: Review of a Unique Congenital Anomaly.” Dermatology and Therapy 6(2): 143–149, DOI: 10.1007/s13555-016-0109-6.

McDonald JH 2011. “Darwin’s tubercle: The myth.” pp. 26–27 in: Myths of Human Genetics. Sparky House Publishing, Baltimore.

Meyer L 1871. Ueber das Darwin’sche Spitzohr. Archiv für pathologische Anatomie und Physiologie und für klinische Medicin 53(2-3): 485–492.

Nickles M 1998. “Humans as a Case Study for the

Evidence of Evolution.” Reports of the National Center for Science Education 18(5): 24–27(also online as ENSI-article, “Twelve Lines of Evidence for the Evolution of Humans & Other Primates”).

Quelprud T 1936. Zur Erblichkeit des Darwinschen Höckerchens. Zeitschrift für Morphologie und Anthropologie34: 343–363.

Wells J 2000. Icons of Evolution: Science or Myth? Regnery Publishing, Washington, D.C., 362 pp.

Wells J 2017. Zombie Science. More Icons of Evolution.Discovery Institute Press, Seattle, 238 pp.

Wikipedia. “Darwin’s tubercle.”

Günter Bechly

In a recent post for Evolution News, we discussed vestigial structures as alleged evidence for evolution ((Chaffee 2017). As an illustration, the article featured an image of the auricular tubercles or “Darwin’s ear points,” a bump-like thickening on the helix of the auricle (exterior ear) of many people that is often claimed to be an atavistic vestige of the pointy ear tip found in monkeys. Evolutionists say the feature proves a shared ancestry of humans with lower primates.

The bump was originally discovered by the celebrated British sculptor Thomas Woolner, who informed Charles Darwin about it. In Darwin (1871:15-17) cited this structure as probable evidence for common ancestry of humans and monkeys. However, at the same time there were already published doubts about this interpretation (Meyer 1871), mainly because of the variability in humans.

Nevertheless, the claim that Darwin’s tubercle is an atavistic structure is still often heard today. Martin Nickels (1998), an anthropologist at Illinois State University, presented Darwin’s tubercle among his “Twelve Lines of Evidence for the Evolution of Humans & Other Primates,” which was featured at the Talk Origins website and published in the 1998 Creation-Evolution issue of the Reports of the National Center for Science Education. In the Wikipedia articles on “Vestigiality” and “Human Vestigiality,” the tubercle is mentioned as one example of vestigial structures. Many popular blogs list this feature as strong evidence for human evolution. Here are two examples:

In“WEIT: Human Vestigiality & Atavisms” (March 19, 2011), on the atheist blog Reflections from the Other Side: Leaving Christianity and Embracing Skepticism, the author refers to Jerry Coyne’s book Why Evolution Is True:

I want to add one atavistic feature that Coyne doesn’t mention: a tiny, almost imperceptible point on the outer rim of the ear known as Darwin’s tubercle.Only 10% of the population has it, but I’m lucky enough to be part of that statistic. Darwin’s tubercle demonstrates our common ancestry with other primates, which have significantly more prominent pointed ears, possibly to help funnel sound into the auditory canal. Below is my ear, a macaque’s ear and an example illustration from Darwin’s The Descent of Man.

It’s both startling and fascinating to realize that I carry tangible, visible evidence for evolution with me wherever I go. And by no means is this connection to the past is something to be ashamed of. On the contrary, to bear such tokens of our history just serves as a reminder of how far our species has come.

In “I Have Primitive Ears” (April 28, 2012), on the blog Rosa Rubicondior: Religion, science and politics from a centre-left atheist humanist. The blog religious frauds tell lies about, another writer observes;

I’m not one to boast, but I have primitive ears. I have the sort of ears of which my remote ancestors might have been proud, if they had had the cognitive ability to be proud.

I have Darwin’s Tubercles … It is a vestige of the ear point found in many simians and, presumably, in our common ancestors.

These are pretty strong claims, from the usual suspects. Yet there are two problems that show Darwin’s tubercles represent an example of evolutionary myth-making.

The first problem, a minor one, concerns a failed prediction. If Darwin’s tubercle were a homologue and an atavistic remnant of the pointy ears of monkeys, we should expect to find this structure in other apes, too, and especially in chimpanzees. The latter, of course, are claimed to be our closest relatives, and have rounded exterior ears similar to humans. According to personal information from British zoologist Edwin Ray Lankester, Darwin (1871:15) briefly mentioned that a chimp from the Zoological Garden at Hamburg did possess this feature. Of course, such dubious hearsay does not qualify as scientific evidence. Indeed, in their recent comprehensive literature review about Darwins’s tubercle, Loh & Cohen (2016) did not mention any record from apes. Likewise, I could not find any descriptions or images anywhere in literature or online that document a chimp ear with a Darwin’s tubercle. All available images of chimp ears do not show anything like a Darwin’s tubercle. So the evolutionary prediction seems to be refuted or at least highly dubious, at least until proven otherwise.

Darwin, in his fervor to present evidence for evolution, cannot always be trusted. This is also shown by the case of his figure (Darwin 1871: fig. 3) of an alleged orangutan fetus featuring a pointy ear unlike that of adult apes. Darwin considered this a kind of ontogenetic recapitulation of evolution. However, the claim is simply false, as Ankel-Simons (2010: 433) mentions:

Schultz (1965, 1969) states that the pointed ear of an “orangutan foetus” that was pictured and described by Darwin (1871) was caused by a deformation of that particular fetus, which Schultz was able to inspect. … Moreover, in Schultz’s judgment, the particular fetus is that of a gibbon and not of an orangutan.

The second problem is much more damaging to the atavism hypothesis. Pointed ear tips are a feature in many monkey species. It is present in all members of the concerned species and always symmetrically present on both ears in both sexes. This strongly suggests that the structure is genetically based and inherited. However, in humans, the feature shows great variability and occurs, for example, in only 10 percent of Spanish adults, 40 percent of Indian adults, and 58 percent of Swedish school children. Some people only have this tubercle on one ear. In half of the pairs of identical twins that were studied, only one of the twins had the ear bumps (Quelprud 1936).

Because of this evidence, and based as well on two genetic studies, McDonald (2011) concluded in an article about what he called the “myth” of Darwin’s tubercle:

The family and twin studies strongly indicate that Darwin’s tubercle is not determined by a single gene with two alleles, and there may be very little genetic influence on the trait at all. You should not use Darwin’s tubercle to demonstrate basic genetics.

But if these ear bumps have no genetic cause, but instead represent environmentally induced developmental accidents, they simply cannot be considered atavistic structures. There is no proof here of common ancestry of humans and monkeys!

Ankel-Simons (2010: 433) thus writes in his standard textbook on Primate Anatomy:

This point of the ear auricle has gone into natural history lore as “tuberculum Darwini” or “Darwin’s point.” It is still regarded by many as an atavism in humans, where the point is actually rarely found. Many human anatomy texts compare the “auricular tubercle of Darwin” with the pointed ears of “adult monkeys.” Lasinsky, however, shows that the two structures have nothing in common. The auricular tubercle of Darwin has had a rather exaggerated revival in the very pointed ears of alien “Vulcans” who evolved from the fantasy of the creators of Star Trek and Star Trek: The Next Generation.

So we can safely conclude that Darwin’s tubercle must be added to the ever-growing list of what Jonathan Wells calls Icons of Evolution (Wells 2000). Rather than modern science, they are debunked science fiction. But as Wells (2017) has also shown, such Zombie Science is hard to kill. It always creeps back from some dark corner of the Internet.

Yet we should add that there is a much more fundamental problem weighing against vestigiality as evidence for evolution and common ancestry.

Critics of evolution often refer to the discovery of function for allegedly vestigial organs, such as the human appendix, tonsils, and coccyx, or the tiny pelvic bones in whales (Klinghoffer 2014). The critics argue that such “vestigial” organs are equally compatible with the design hypothesis. Evolutionists, meanwhile, usually respond by emphasizing that vestigiality does not imply absence of any function. Instead, it is commonly defined as “the retention during the process of evolution of genetically determined structures or attributes that have lost some or all of their ancestral function in a given species” (Wikipedia,“Vestigiality” ).

However, if the total or partial absence of function is restricted only to an assumed ancestral function, then common ancestry is itself assumed in the definition of the concept of vestigiality. The result is that vestigiality cannot be used as evidence for common ancestry without committing the logical fallacy of begging the question, or circular reasoning.

Alternatively, some evolutionists say that in vestigial organs, homology and not functionality is the crucial issue. However, this creates the same problem, on a different level. Just like vestigiality, the concept of homology presupposes common ancestry and therefore cannot be used to prove it. (See Wikipedia, “Homology”: “In biology, homology is the existence of shared ancestry between a pair of structures, or genes, in different taxa.”) The presumption of common ancestry is not optional for homology, because without the notion of common ancestry one could not distinguish homologous similarities from convergent similarities.

Consequently, large parts of the allegedly strongest evidence for evolution from comparative morphology indeed are invalid and based on logically fallacious reasoning.

Literature:

Ankel-Simons F 2010. Primate Anatomy: An Introduction. Academic Press, Cambridge, 752 pp.

Chaffee S 2017. “Theology in Biology Class: Vestigial Structures as Evidence for Evolution.” Evolution News, September 21, 2017.

Darwin C 1871. Chap. I. Rudiments. p. 15 in: The Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex. John Murray, London.

Klinghoffer D 2014. “Now It’s Whale Hips: Another Icon of Darwinian Evolution, Vestigial Structures, Takes a Hit.” Evolution News, September 15, 2014.

Lasinsky W 1960. Äußeres Ohr. pp. 41–74 in: Hofer HO, Schultz AH, Starck D (eds). Primatologia, Handbook of Primatology Vol. II. Karger, Basel.

Loh TY, Cohen PR 2016. “Darwin’s Tubercle: Review of a Unique Congenital Anomaly.” Dermatology and Therapy 6(2): 143–149, DOI: 10.1007/s13555-016-0109-6.

McDonald JH 2011. “Darwin’s tubercle: The myth.” pp. 26–27 in: Myths of Human Genetics. Sparky House Publishing, Baltimore.

Meyer L 1871. Ueber das Darwin’sche Spitzohr. Archiv für pathologische Anatomie und Physiologie und für klinische Medicin 53(2-3): 485–492.

Nickles M 1998. “Humans as a Case Study for the

Evidence of Evolution.” Reports of the National Center for Science Education 18(5): 24–27(also online as ENSI-article, “Twelve Lines of Evidence for the Evolution of Humans & Other Primates”).

Quelprud T 1936. Zur Erblichkeit des Darwinschen Höckerchens. Zeitschrift für Morphologie und Anthropologie34: 343–363.

Wells J 2000. Icons of Evolution: Science or Myth? Regnery Publishing, Washington, D.C., 362 pp.

Wells J 2017. Zombie Science. More Icons of Evolution.Discovery Institute Press, Seattle, 238 pp.

Wikipedia. “Darwin’s tubercle.”

E.T's design filter?

The Search for Terrestrial Intelligence – An Exercise in Intelligent Design

Evolution News | @DiscoveryCSC

We humans take our own intelligence for granted. We know when we make things on purpose, and we use “folk psychology” to attribute similar intentionality and motivation to our fellows. Most of the time, we have an intuitive sense of design for human artifacts, even if we didn’t observe them coming into existence. Can we project that kind of reasoning onto extraterrestrials? The question may sound strange, but playing along with it might illuminate some principles of intelligent design.

In Live Science, Sarah B. Puschman showed a picture of crop circles that she says look like “alien” works of art. She’s not talking about those elaborate artworks created in the middle of the night by hoaxers, but by the rather ordinary circles standing out in the desert due to farming practices (see the photo above).

To make the circles pictured, water is drawn to the surface and sprinkled onto crops through slowly spinning pipes using a process called center-pivot irrigation.

The water “is drawn” — by whom? By human beings using intelligent design, obviously. Pipes don’t create themselves. Pipes don’t rotate from a pivot by themselves. Humans took natural materials — metal, water, and seeds — and arranged them in a way that yields crop circles. They can really stand out from the surroundings when seen from an aircraft. How strong would the design inference be for alien intelligences, if irrigation circles were the only things they saw?

Circles can be made naturally: for instance, volcanic craters, calderas, and impact scars. There’s a large circular lake in Canada formed from a meteorite. Any geological process on earth that spreads material out from a center could form a circle. What makes the irrigation circle different? An artesian well might spread water out in a circle on a very flat plain, after all, allowing plants to grow within its reach. Looking at these crop circles, though, one knows immediately they were designed.

For one thing, there are lots of them laid out with regular spacing. For another, they are too perfect; no irregularities. Radioisotopes can create perfect circles (actually spheres) in rock, but those are not equally spaced. It’s highly improbable that volcanoes or meteorites would form circles in a regular grid pattern. While one crop circle might leave the design inference open to question, a lot of them with regular spacing clinches it, for humans at least. But could aliens, without knowledge of human practices, arrive at the same conclusion?

Some things obvious to us might not be obvious to sentient beings unfamiliar with human technology. We would have similar challenges on alien worlds. Visiting aliens might need a little more evidence at ground level. But even if they couldn’t find someone to ask, it seems likely they would arrive at a robust inference (if we assume that logical reasoning is universal among intelligent beings).

Are these circles, and the ingredients making them, natural occurrences on our strange planet? Alien design theorists might try to see if pipes are found in other locations, such as in forests, in random orientations. They might investigate whether water normally springs out of devices that are regularly spaced along the pipes anywhere else. Natural geysers might give them pause, but only temporarily, when they contrast their variability with the high degree of regularity in the irrigation pipes. They might consider whether the plants growing in the circles, whether wheat, potatoes, or chamomile, grow naturally outside circles or in the occasional oasis. And if math and geometry are available to all intelligent minds, as the human designers of the Voyager Golden Records assumed, we would expect aliens to be impressed by the extreme regularity of the geometry of crop circles. They might suspect functional coherence in the crops, that they are being grown for a purpose — even if the aliens can’t eat them. Lastly, they might find aesthetic beauty in the patterns.

We’re assuming a lot about alien minds, but we already know the answer as humans: Yes, these crop circles are designed for a purpose. If SETI believers expect to be able to distinguish alien artifacts from natural causes, they can certainly also expect aliens to decipher ours.

Crop Art

Puschman ends with a discussion of the artistic crop circles that appear within corn or wheat fields in the morning. When the crop-art fad first caught national attention, there were some who tried to find natural causes. Others wondered if we were being visited by UFOs, or whether aliens beamed microwaves to flatten the crops. As the patterns became more intricate, few were the observers who did not attribute them to intelligent design.

She refers to an August 2011 article in Popular Science by Rebecca Boyle about crop art. By then, when designs had become extremely elaborate, most people had given up on natural causes.

In the collective modern imagination, crop circles are usually attributed to either aliens or a vast human conspiracy; possibly both. Some circle-watchers believe the designs are landing strips, maybe, or some kind of communiqué from outer space. Others argue crop circles are the result of secret government tests, or perhaps secret codes meant to convey information to satellites and aerial drones.

Boyle turned from the origin question to the how question. How were they made? She talks to a scientist, who speculated that they required advanced technology to make, to an actual crop art maker, who says it’s easy to do with simple materials, a GPS device, and a portable computer.

The “how” question, though, lies outside of intelligent design theory, as does the “who” question. We just want to know if the circles are designed.

Using Dembski’s design filter, we can formulate a robust design inference by first ruling out chance and natural law. Chance can accomplish some pretty improbable events, but if we decide the probability is low, our work is not done. Laws of physics might bring circles about (like the volcano, meteorite, or artesian spring). If the circle had to happen, given a meteor strike, then it’s no longer a contingent phenomenon, so natural law is the preferred inference for a crater.

Contingency allows our minds to progress to the final stage of the design filter: Is there an independently specified pattern? Perfect circles in regular grids have low probability. They are also contingent; no known natural law requires them to form that way (even the natural “fairy circles” we’ve discussed previously lack that degree of geometric specificity). We know, however, from every other instance of regularly spaced set circles, such as in parking lot bump strips, corrugated sheet metal perforations, or polka dots in fabric, that human intelligence was the cause.

If aliens are intelligent enough to design space ships, they most likely understand math and logic to a high degree. There may not be any such aliens. We certainly haven’t detected any yet. But by projecting what we know about intelligence onto theoretical intelligences in a “reverse SETI” thought experiment, we learn whether a Search for Terrestrial Intelligence justifies a design inference.

Finally, let’s consider aliens encountering two spacecraft beyond Earth: Voyager and Cassini. The twin Voyager spacecraft were launched with the express intention of communicating to alien intelligences, even though we know nothing about such intelligences. Presumably, a craft with that high a degree of complex specified information (CSI) would easily pass the design inference, even if aliens could not decipher the inscriptions or functions of the craft. It would certainly stand out from all the asteroids they know!

All the molecules of Cassini, however, were disrupted on September 15 as it burned up in the atmosphere. Cassini isn’t “gone” but it has become a part of Saturn. The CSI of all its exquisitely sensitive instruments, its onboard computers, its subsystems, has been obliterated. The chance that aliens could detect anomalous molecules in the atmosphere of Saturn seems remote; that would be the only possible way now to determine that something unusual happened in the planet’s atmosphere. From this we learn that it is far easier to destroy CSI than to create it.

If they ever locate the intact Huygens probe on Titan, though, that’s a different matter. They might deduce that an object with those characteristics could not have flown itself to its location. By observing the probe carefully, they would know not only that it was designed, but there must have existed a craft capable of delivering it to Titan that was also designed. If they determined that it came from planet Earth, they might even be able to reverse-engineer some of the design requirements for the mother ship.

In short, we have seen that role-playing alien intelligences is not only idle speculation. It can help us reason our way through principles of intelligent design about real-world phenomena. Perhaps somewhere out there, extraterrestrials reading this — if they could — would signal their agreement.

Evolution News | @DiscoveryCSC

We humans take our own intelligence for granted. We know when we make things on purpose, and we use “folk psychology” to attribute similar intentionality and motivation to our fellows. Most of the time, we have an intuitive sense of design for human artifacts, even if we didn’t observe them coming into existence. Can we project that kind of reasoning onto extraterrestrials? The question may sound strange, but playing along with it might illuminate some principles of intelligent design.

In Live Science, Sarah B. Puschman showed a picture of crop circles that she says look like “alien” works of art. She’s not talking about those elaborate artworks created in the middle of the night by hoaxers, but by the rather ordinary circles standing out in the desert due to farming practices (see the photo above).

To make the circles pictured, water is drawn to the surface and sprinkled onto crops through slowly spinning pipes using a process called center-pivot irrigation.

The water “is drawn” — by whom? By human beings using intelligent design, obviously. Pipes don’t create themselves. Pipes don’t rotate from a pivot by themselves. Humans took natural materials — metal, water, and seeds — and arranged them in a way that yields crop circles. They can really stand out from the surroundings when seen from an aircraft. How strong would the design inference be for alien intelligences, if irrigation circles were the only things they saw?

Circles can be made naturally: for instance, volcanic craters, calderas, and impact scars. There’s a large circular lake in Canada formed from a meteorite. Any geological process on earth that spreads material out from a center could form a circle. What makes the irrigation circle different? An artesian well might spread water out in a circle on a very flat plain, after all, allowing plants to grow within its reach. Looking at these crop circles, though, one knows immediately they were designed.

For one thing, there are lots of them laid out with regular spacing. For another, they are too perfect; no irregularities. Radioisotopes can create perfect circles (actually spheres) in rock, but those are not equally spaced. It’s highly improbable that volcanoes or meteorites would form circles in a regular grid pattern. While one crop circle might leave the design inference open to question, a lot of them with regular spacing clinches it, for humans at least. But could aliens, without knowledge of human practices, arrive at the same conclusion?

Some things obvious to us might not be obvious to sentient beings unfamiliar with human technology. We would have similar challenges on alien worlds. Visiting aliens might need a little more evidence at ground level. But even if they couldn’t find someone to ask, it seems likely they would arrive at a robust inference (if we assume that logical reasoning is universal among intelligent beings).

Are these circles, and the ingredients making them, natural occurrences on our strange planet? Alien design theorists might try to see if pipes are found in other locations, such as in forests, in random orientations. They might investigate whether water normally springs out of devices that are regularly spaced along the pipes anywhere else. Natural geysers might give them pause, but only temporarily, when they contrast their variability with the high degree of regularity in the irrigation pipes. They might consider whether the plants growing in the circles, whether wheat, potatoes, or chamomile, grow naturally outside circles or in the occasional oasis. And if math and geometry are available to all intelligent minds, as the human designers of the Voyager Golden Records assumed, we would expect aliens to be impressed by the extreme regularity of the geometry of crop circles. They might suspect functional coherence in the crops, that they are being grown for a purpose — even if the aliens can’t eat them. Lastly, they might find aesthetic beauty in the patterns.

We’re assuming a lot about alien minds, but we already know the answer as humans: Yes, these crop circles are designed for a purpose. If SETI believers expect to be able to distinguish alien artifacts from natural causes, they can certainly also expect aliens to decipher ours.

Crop Art

Puschman ends with a discussion of the artistic crop circles that appear within corn or wheat fields in the morning. When the crop-art fad first caught national attention, there were some who tried to find natural causes. Others wondered if we were being visited by UFOs, or whether aliens beamed microwaves to flatten the crops. As the patterns became more intricate, few were the observers who did not attribute them to intelligent design.

She refers to an August 2011 article in Popular Science by Rebecca Boyle about crop art. By then, when designs had become extremely elaborate, most people had given up on natural causes.

In the collective modern imagination, crop circles are usually attributed to either aliens or a vast human conspiracy; possibly both. Some circle-watchers believe the designs are landing strips, maybe, or some kind of communiqué from outer space. Others argue crop circles are the result of secret government tests, or perhaps secret codes meant to convey information to satellites and aerial drones.

Boyle turned from the origin question to the how question. How were they made? She talks to a scientist, who speculated that they required advanced technology to make, to an actual crop art maker, who says it’s easy to do with simple materials, a GPS device, and a portable computer.

The “how” question, though, lies outside of intelligent design theory, as does the “who” question. We just want to know if the circles are designed.

Using Dembski’s design filter, we can formulate a robust design inference by first ruling out chance and natural law. Chance can accomplish some pretty improbable events, but if we decide the probability is low, our work is not done. Laws of physics might bring circles about (like the volcano, meteorite, or artesian spring). If the circle had to happen, given a meteor strike, then it’s no longer a contingent phenomenon, so natural law is the preferred inference for a crater.