The Holy Scriptures, the inspired Word of Jehovah, acknowledged as the greatest book of all times because of its antiquity, its total circulation, the number of languages into which it has been translated, its surpassing greatness as a literary masterpiece, and its overwhelming importance to all mankind. Independent of all other books, it imitates no other. It stands on its own merits, giving credit to its unique Author. The Bible is also distinguished as having survived more violent controversy than any other book, hated as it is by many enemies.

Name. The English word “Bible” comes through the Latin from the Greek word bi·bliʹa, meaning “little books.” This, in turn, is derived from biʹblos, a word that describes the inner part of the papyrus plant out of which a primitive form of paper was made. The Phoenician city of Gebal, famous for its papyrus trade, was called by the Greeks “Byblos.” (See Jos 13:5, ftn.) In time bi·bliʹa came to describe various writings, scrolls, books, and eventually the collection of little books that make up the Bible. Jerome called this collection Bibliotheca Divina, the Divine Library.

Jesus and writers of the Christian Greek Scriptures referred to the collection of sacred writings as “the Scriptures,” or “the holy Scriptures,” “the holy writings.” (Mt 21:42; Mr 14:49; Lu 24:32; Joh 5:39; Ac 18:24; Ro 1:2; 15:4; 2Ti 3:15, 16) The collection is the written expression of a communicating God, the Word of God, and this is acknowledged in phrases such as “expression of Jehovah’s mouth” (De 8:3), “sayings of Jehovah” (Jos 24:27), “commandments of Jehovah” (Ezr 7:11), “law of Jehovah,” “reminder of Jehovah,” “orders from Jehovah” (Ps 19:7, 8), “word of Jehovah” (Isa 38:4), ‘utterance of Jehovah’ (Mt 4:4), “Jehovah’s word” (1Th 4:15). Repeatedly these writings are spoken of as “sacred pronouncements of God.”—Ro 3:2; Ac 7:38; Heb 5:12; 1Pe 4:11.

Divisions. Sixty-six individual books from Genesis to Revelation make up the Bible canon. The choice of these particular books, and the rejection of many others, is evidence that the Divine Author not only inspired their writing but also carefully guarded their collection and preservation within the sacred catalog. (See APOCRYPHA; CANON.) Thirty-nine of the 66 books, making up three quarters of the Bible’s contents, are known as the Hebrew Scriptures, all having been initially written in that language with the exception of a few small sections written in Aramaic. (Ezr 4:8–6:18; 7:12-26; Jer 10:11; Da 2:4b–7:28) By combining some of these books, the Jews had a total of only 22 or 24 books, yet these embraced the same material. It also appears to have been their custom to subdivide the Scriptures into three parts—‘the law of Moses, the Prophets, and the Psalms.’ (Lu 24:44; see HEBREW SCRIPTURES.) The last quarter of the Bible is known as the Christian Greek Scriptures, so designated because the 27 books comprising this section were written in Greek. The writing, collecting, and arrangement of these books within the Bible’s canon also demonstrate Jehovah’s supervision from start to finish.—See CHRISTIAN GREEK SCRIPTURES.

Subdividing the Bible into chapters and verses (KJ has 1,189 chapters and 31,102 verses) was not done by the original writers, but it was a very useful device added centuries later. The Masoretes divided the Hebrew Scriptures into verses; then in the 13th century of our Common Era chapter divisions were added. Finally, in 1553 Robert Estienne’s edition of the French Bible was published as the first complete Bible with the present chapter and verse divisions.

The 66 Bible books all together form but a single work, a complete whole. As the chapter and verse marks are only convenient aids for Bible study and are not intended to detract from the unity of the whole, so also is the sectioning of the Bible, which is done according to the predominant language in which the manuscripts have come down to us. We, therefore, have both the Hebrew and Greek Scriptures, with “Christian” added to the latter to distinguish them from the Greek Septuagint, which is the Hebrew portion of the Scriptures translated into Greek.

“Old Testament” and “New Testament.” Today it is a common practice to refer to the Scriptures written in Hebrew and Aramaic as the “Old Testament.” This is based on the reading in 2 Corinthians 3:14 in the Latin Vulgate and the King James Version. However, the rendering “old testament” in this text is incorrect. The Greek word di·a·theʹkes here means “covenant,” as it does in the other 32 places where it occurs in the Greek text. Many modern translations correctly read “old covenant.” (NE, RS, JB) The apostle Paul is not referring to the Hebrew and Aramaic Scriptures in their entirety. Neither does he mean that the inspired Christian writings constitute a “new testament (or, covenant).” The apostle is speaking of the old Law covenant, which was recorded by Moses in the Pentateuch and which makes up only a part of the pre-Christian Scriptures. For this reason he says in the next verse, “whenever Moses is read.”

Hence, there is no valid basis for the Hebrew and Aramaic Scriptures to be called the “Old Testament” and for the Christian Greek Scriptures to be called the “New Testament.” Jesus Christ himself referred to the collection of sacred writings as “the Scriptures.” (Mt 21:42; Mr 14:49; Joh 5:39) The apostle Paul referred to them as “the holy Scriptures,” “the Scriptures,” and “the holy writings.”—Ro 1:2; 15:4; 2Ti 3:15.

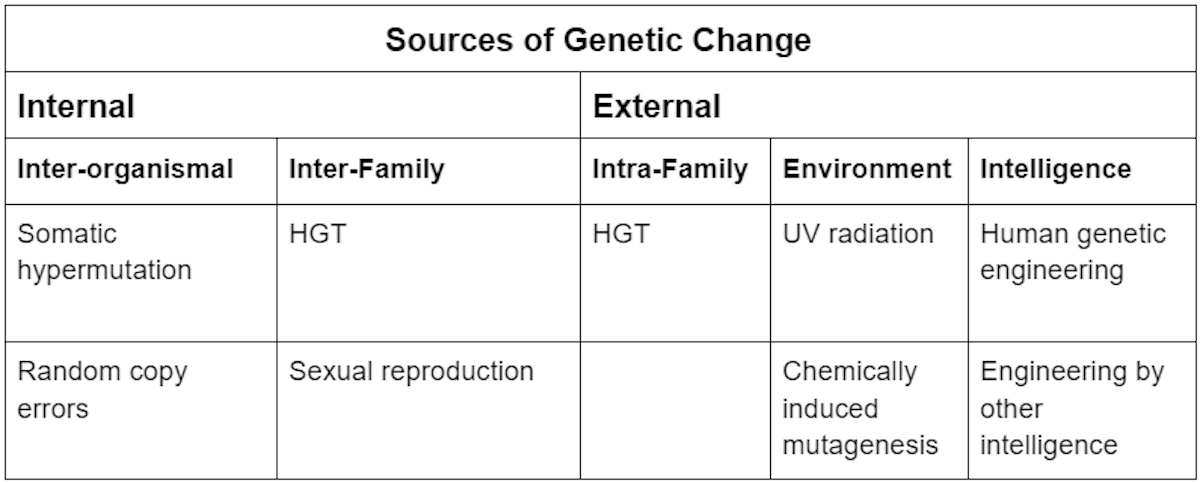

Authorship. The accompanying table shows that about 40 human secretaries or scribes were used by the one Author to record the inspired Word of Jehovah. “All Scripture is inspired of God,” and this includes the writings in the Christian Greek Scriptures along with “the rest of the Scriptures.” (2Ti 3:16; 2Pe 3:15, 16) This expression “inspired of God” translated the Greek phrase the·oʹpneu·stos, meaning “God-breathed.” By ‘breathing’ on faithful men, God caused his spirit, or active force, to become operative upon them and directed what he wanted recorded, for, as it is written, “prophecy was at no time brought by man’s will, but men spoke from God as they were borne along by holy spirit.”—2Pe 1:21; Joh 20:21, 22; see INSPIRATION.

This unseen holy spirit of God is his symbolic “finger.” Therefore, when men saw Moses perform supernatural feats they exclaimed: “It is the finger of God!” (Ex 8:18, 19; compare with Jesus’ words at Mt 12:22, 28; Lu 11:20.) In a similar display of divine power “God’s finger” began the writing of the Bible by carving out the Ten Commandments on stone tablets. (Ex 31:18; De 9:10) It would, therefore, be a simple matter for Jehovah to use men as his scribes even though some were “unlettered and ordinary” in scholastic training (Ac 4:13), and regardless of whether the individual was by trade a shepherd, farmer, tentmaker, fisherman, tax collector, physician, priest, prophet, or king. Jehovah’s active force put the thoughts into the writer’s mind and, in certain instances, allowed him to express the divine thought in his own words, thus permitting personality and individual traits to show through the writing, yet at the same time maintaining a superb oneness in theme and in purpose throughout. In this way the resultant Bible, reflecting as it does the mind and will of Jehovah, exceeded in wealth and in scope the writings of mere men. The Almighty God saw to it that his written Word of truth was in language easily understood and easily translated into practically any tongue.

No other book took so long to complete as the Bible. In 1513 B.C.E. Moses began Bible writing. Other sacred writings were added to the inspired Scriptures until sometime after 443 B.C.E. when Nehemiah and Malachi completed their books. Then there was a gap in Bible writing for almost 500 years, until the apostle Matthew penned his historic account. Nearly 60 years later John, the last of the apostles, contributed his Gospel and three letters to complete the Bible’s canon. So, all together, a period of some 1,610 years was involved in producing the Bible. All the cowriters were Hebrews and, hence, part of that people “entrusted with the sacred pronouncements of God.”—Ro 3:2.

The Bible is not an unrelated assortment or collection of heterogeneous fragments from Jewish and Christian literature. Rather, it is an organizational book, highly unified and interconnected in its various segments, which indeed reflect the systematic orderliness of the Creator-Author himself. God’s dealings with Israel in giving them a comprehensive law code as well as regulations governing matters even down to small details of camp life—things that were later mirrored in the Davidic kingdom as well as in the congregational arrangement among first-century Christians—reflect and magnify this organizational aspect of the Bible.

Contents. In contents this Book of Books reveals the past, explains the present, and foretells the future. These are matters that only He who knows the end from the beginning could author. (Isa 46:10) Starting at the beginning by telling of the creation of heaven and earth, the Bible next gives a sweeping account of the events that prepared the earth for man’s habitation. Then the truly scientific explanation of the origin of man is revealed—how life comes only from a Life-Giver—facts that only the Creator now in the role of Author could explain. (Ge 1:26-28; 2:7) With the account of why men die, the overriding theme that permeates the whole Bible was introduced. This theme, the vindication of Jehovah’s sovereignty and the ultimate fulfillment of his purpose for the earth, by means of his Kingdom under Christ, the promised Seed, was wrapped up in the first prophecy concerning ‘the seed of the woman.’ (Ge 3:15) More than 2,000 years passed before this promise of a “seed” was again mentioned, God telling Abraham: “By means of your seed all nations of the earth will certainly bless themselves.” (Ge 22:18) Over 800 years later, renewed assurance was given to Abraham’s descendant King David, and with the passing of more time Jehovah’s prophets kept this flame of hope burning brightly. (2Sa 7:12, 16; Isa 9:6, 7) More than 1,000 years after David and 4,000 years after the original prophecy in Eden, the Promised Seed himself appeared, Jesus Christ, the legal heir to “the throne of David his father.” (Lu 1:31-33; Ga 3:16) Bruised in death by the earthly seed of the “serpent,” this “Son of the Most High” provided the ransom purchase price for the life rights lost to Adam’s offspring, thus providing the only means whereby mankind can get everlasting life. He was then raised on high, there to await the appointed time to hurl “the original serpent, the one called Devil and Satan,” down to the earth, finally to be destroyed forever. Thus the magnificent theme announced in Genesis and developed and enlarged upon throughout the balance of the Bible is, in the closing chapters of Revelation, brought to a glorious climax as Jehovah’s grand purpose by means of his Kingdom is made apparent.—Re 11:15; 12:1-12, 17; 19:11-16; 20:1-3, 7-10; 21:1-5; 22:3-5.

Through this Kingdom under Christ the Promised Seed, Jehovah’s sovereignty will be vindicated and his name will be sanctified. Following through on this theme, the Bible magnifies God’s personal name to a greater extent than any other book; the name occurs 6,979 times in the Hebrew Scripture portion of the New World Translation. That is in addition to the use of the shorter form “Jah” and the scores of instances where it combines to form other names like “Jehoshua,” meaning “Jehovah Is Salvation.” (See JEHOVAH [Importance of the Name].) We would not know the Creator’s name, the great issue involving his sovereignty raised by the Edenic rebellion, or God’s purpose to sanctify his name and vindicate his sovereignty before all creation if these things were not revealed in the Bible.

In this library of 66 little books the theme of the Kingdom and Jehovah’s name are closely interwoven with information on many subjects. Its reference to fields of knowledge such as agriculture, architecture, astronomy, chemistry, commerce, engineering, ethnology, government, hygiene, music, poetry, philology, and tactical warfare is only incidental to development of the theme; not as a treatise. Nevertheless, it contains a veritable treasure-house of information for the archaeologists and paleographers.

As an accurate historical work and one that penetrates the past to great depths, the Bible far surpasses all other books. However, it is of much greater value in the field of prophecy, foretelling as it does the future that only the King of Eternity can reveal with accuracy. The march of world powers down through the centuries, even to the rise and ultimate demise of present-day institutions, was prophetically related in the Bible’s long-range prophecies.

God’s Word of truth in a very practical way sets men free from ignorance, superstitions, human philosophies, and senseless traditions of men. (Joh 8:32) “The word of God is alive and exerts power.” (Heb 4:12) Without the Bible we would not know Jehovah, would not know the wonderful benefits resulting from Christ’s ransom sacrifice, and would not understand the requirements that must be met in order to get everlasting life in or under God’s righteous Kingdom.

The Bible is a most practical book in other ways too, for it gives sound counsel to Christians on how to live now, how to carry on their ministry, and how to survive this anti-God, pleasure-seeking system of things. Christians are told to “quit being fashioned after this system of things” by making their minds over from worldly thinking, and this they can do by having the same mental attitude of humility “that was also in Christ Jesus” and by stripping off the old personality and putting on the new one. (Ro 12:2; Php 2:5-8; Eph 4:23, 24; Col 3:5-10) This means displaying the fruitage of God’s spirit, “love, joy, peace, long-suffering, kindness, goodness, faith, mildness, self-control”—subjects on which so much is written throughout the Bible.—Ga 5:22, 23; Col 3:12-14.

Authenticity. The veracity of the Bible has been assailed from many quarters, but none of these efforts has undermined or weakened its position in the least.

Bible history. Sir Isaac Newton once said: “I find more sure marks of authenticity in the Bible than in any profane history whatsoever.” (Two Apologies, by R. Watson, London, 1820, p. 57) Its integrity to truth proves sound on any point that might be tested. Its history is accurate and can be relied upon. For example, what it says about the fall of Babylon to the Medes and Persians cannot be successfully contradicted (Jer 51:11, 12, 28; Da 5:28), neither can what it says about people like Babylonian Nebuchadnezzar (Jer 27:20; Da 1:1); Egyptian King Shishak (1Ki 14:25; 2Ch 12:2); Assyrians Tiglath-pileser III and Sennacherib (2Ki 15:29; 16:7; 18:13); the Roman emperors Augustus, Tiberius, and Claudius (Lu 2:1; 3:1; Ac 18:2); Romans such as Pilate, Felix, and Festus (Ac 4:27; 23:26; 24:27); nor what it says about the temple of Artemis at Ephesus and the Areopagus at Athens (Ac 19:35; 17:19-34). What the Bible says about these or any other places, people, or events is historically accurate in every detail.—See ARCHAEOLOGY.

Races and languages. What the Bible says about races and languages of mankind is also true. All peoples, regardless of stature, culture, color, or language, are members of one human family. The threefold division of the human family into the Japhetic, Hamitic, and Semitic races, all descending from Adam through Noah, cannot be successfully disputed. (Ge 9:18, 19; Ac 17:26) Says Sir Henry Rawlinson: “If we were to be guided by the mere intersection of linguistic paths, and independently of all reference to the Scriptural record, we should still be led to fix on the plains of Shinar, as the focus from which the various lines had radiated.”—The Historical Evidences of the Truth of the Scripture Records, by G. Rawlinson, 1862, p. 287; Ge 11:2-9.

Practicality. The Bible’s teachings, examples, and doctrines are most practical for modern man. The righteous principles and high moral standards contained in this book set it apart as far above all other books. Not only does the Bible answer important questions but it also provides many practical suggestions which, if followed, would do much to raise the physical and mental health of earth’s population. The Bible lays down principles of right and wrong that serve as a straightedge for just business dealings (Mt 7:12; Le 19:35, 36; Pr 20:10; 22:22, 23), industriousness (Eph 4:28; Col 3:23; 1Th 4:11, 12; 2Th 3:10-12), clean moral conduct (Ga 5:19-23; 1Th 4:3-8; Ex 20:14-17; Le 20:10-16), upbuilding associations (1Co 15:33; Heb 10:24, 25; Pr 5:3-11; 13:20), good family relationships (Eph 5:21-33; 6:1-4; Col 3:18-21; De 6:4-9; Pr 13:24). As the famous educator William Lyon Phelps once said: “I believe a knowledge of the Bible without a college course is more valuable than a college course without a Bible.” (The New Dictionary of Thoughts, p. 46) Regarding the Bible, John Quincy Adams wrote: “It is of all books in the world, that which contributes most to make men good, wise, and happy.”—Letters of John Quincy Adams to His Son, 1849, p. 9.

Scientific accuracy. When it comes to scientific accuracy the Bible is not lacking. Whether describing the progressive order of earth’s preparation for human habitation (Ge 1:1-31), speaking of the earth as being spherical and hung on “nothing” (Job 26:7; Isa 40:22), classifying the hare as a cud chewer (Le 11:6), or declaring, “the soul of the flesh is in the blood” (Le 17:11-14), the Bible is scientifically sound.

Cultures and customs. On points relating to cultures and customs, in no regard is the Bible found to be wrong. In political matters, the Bible always speaks of a ruler by the proper title that he bore at the time of the writing. For example, Herod Antipas and Lysanias are referred to as district rulers (tetrarchs), Herod Agrippa (II) as king, and Gallio as proconsul. (Lu 3:1; Ac 25:13; 18:12) Triumphal marches of victorious armies, together with their captives, were common during Roman times. (2Co 2:14) The hospitality shown to strangers, the Oriental way of life, the manner of purchasing property, legal procedures in making contracts, and the practice of circumcision among the Hebrews and other peoples are referred to in the Bible, and in all these details the Bible is accurate.—Ge 18:1-8; 23:7-18; 17:10-14; Jer 9:25, 26.

Candor. Bible writers displayed a candor that is not found among other ancient writers. From the very outset, Moses frankly reported his own sins as well as the sins and errors of his people, a policy followed by the other Hebrew writers. (Ex 14:11, 12; 32:1-6; Nu 14:1-9; 20:9-12; 27:12-14; De 4:21) The sins of great ones such as David and Solomon were not covered over but were reported. (2Sa 11:2-27; 1Ki 11:1-13) Jonah told of his own disobedience. (Jon 1:1-3; 4:1) The other prophets likewise displayed this same straightforward, candid quality. Writers of the Christian Greek Scriptures showed the same regard for truthful reporting as that displayed in the Hebrew Scriptures. Paul tells of his former sinful course in life; Mark’s failure to stick to the missionary work; and also the apostle Peter’s errors are related. (Ac 22:19, 20; 15:37-39; Ga 2:11-14) Such frank, open reporting builds confidence in the Bible’s claim to honesty and truthfulness.

Integrity. Facts testify to the integrity of the Bible. The Bible narrative is inseparably interwoven with the history of the times. It gives straightforward, truthful instruction in the simplest manner. The guileless earnestness and fidelity of its writers, their burning zeal for truth, and their painstaking effort to attain accuracy in details are what we would expect in God’s Word of truth.—Joh 17:17.

Prophecy. If there is a single point that alone proves the Bible to be the inspired Word of Jehovah it is the matter of prophecy. There are scores of long-range prophecies in the Bible that have been fulfilled. For a partial listing, see the book “All Scripture Is Inspired of God and Beneficial,” pp. 343-346.

Preservation. Today none of the original writings of the Holy Scriptures are known to exist. Jehovah, however, saw to it that copies were made to replace the aging originals. Also, from and after the Babylonian exile, with the growth of many Jewish communities outside Palestine, there was an increasing demand for more copies of the Scriptures. This demand was met by professional copyists who made extraordinary efforts to see that accuracy was attained in their handwritten manuscripts. Ezra was just such a man, “a skilled copyist in the law of Moses, which Jehovah the God of Israel had given.”—Ezr 7:6.

For hundreds of years handwritten copies of the Scriptures continued to be made, during which period the Bible was expanded with the addition of the Christian Greek Scriptures. Translations or versions of these Holy Writings also appeared in other languages. Indeed, the Hebrew Scriptures are honored as the first book of note to be translated into another language. Extant today are thousands of these Bible manuscripts and versions.—See MANUSCRIPTS OF THE BIBLE; VERSIONS.

The first printed Bible, the Gutenberg Bible, came off the press in 1456. Today distribution of the Bible (the whole or in part) has reached over four billion copies in upwards of 2,000 languages. But this has not been accomplished without great opposition from many quarters. Indeed, the Bible has had more enemies than any other book; popes and councils even prohibited the reading of the Bible under penalty of excommunication. Thousands of Bible lovers lost their lives, and thousands of copies of the Bible were committed to the flames. One of the victims in the Bible’s fight to live was translator William Tyndale, who once declared in a discussion with a cleric: “If God spare my life ere many years, I will cause a boy that driveth the plough shall know more of the Scripture than thou doest.”—Actes and Monuments, by John Foxe, London, 1563, p. 514.

All credit and thanksgiving for the Bible’s survival in view of such violent opposition is due Jehovah, the Preserver of his Word. This fact gives added meaning to the apostle Peter’s quotation from the prophet Isaiah: “All flesh is like grass, and all its glory is like a blossom of grass; the grass becomes withered, and the flower falls off, but the saying of Jehovah endures forever.” (1Pe 1:24, 25; Isa 40:6-8) We, therefore, do well to pay “attention to it as to a lamp shining in a dark place” in this 21st century. (2Pe 1:19; Ps 119:105) The man whose “delight is in the law of Jehovah, and in his law he reads in an undertone day and night” and who puts in practice the things he reads is the one who prospers and is happy. (Ps 1:1, 2; Jos 1:8) To him Jehovah’s laws, reminders, orders, commandments, and judicial decisions contained in the Bible are “sweeter than honey,” and the wisdom derived therefrom is “more to be desired than gold, yes, than much refined gold,” for it means his very life.—Ps 19:7-10; Pr 3:13, 16-18; see CANON.

[Chart on page 309]

TABLE OF BIBLE BOOKS IN ORDER COMPLETED

(The order in which the Bible books were written and where each stands in relation to the others is approximate; some dates [and places written] are uncertain. The symbol a. means “after”; b., “before”; and c., “circa” or “about.”)

Hebrew Scriptures (B.C.E.)

Book

Writer

Date Completed

Time Covered

Place Written

Genesis

Moses

1513

“In the beginning” to 1657

Wilderness

Exodus

Moses

1512

1657-1512

Wilderness

Leviticus

Moses

1512

1 month (1512)

Wilderness

Job

Moses

c. 1473

Over 140 years between 1657 and 1473

Wilderness

Numbers

Moses

1473

1512-1473

Wilderness/Plains of Moab

Deuteronomy

Moses

1473

2 months (1473)

Plains of Moab

Joshua

Joshua

c. 1450

1473–c. 1450

Canaan

Judges

Samuel

c. 1100

c. 1450–c. 1120

Israel

Ruth

Samuel

c. 1090

11 years of Judges’ rule

Israel

1 Samuel

Samuel; Gad; Nathan

c. 1078

c. 1180-1078

Israel

2 Samuel

Gad; Nathan

c. 1040

1077–c. 1040

Israel

Song of Solomon

Solomon

c. 1020

—

Jerusalem

Ecclesiastes

Solomon

b. 1000

—

Jerusalem

Jonah

Jonah

c. 844

—

—

Joel

Joel

c. 820 (?)

—

Judah

Amos

Amos

c. 804

—

Judah

Hosea

Hosea

a. 745

b. 804–a. 745

Samaria (District)

Isaiah

Isaiah

a. 732

c. 778–a. 732

Jerusalem

Micah

Micah

b. 717

c. 777-717

Judah

Proverbs

Solomon; Agur; Lemuel

c. 717

—

Jerusalem

Zephaniah

Zephaniah

b. 648

—

Judah

Nahum

Nahum

b. 632

—

Judah

Habakkuk

Habakkuk

c. 628 (?)

—

Judah

Lamentations

Jeremiah

607

—

Nr. Jerusalem

Obadiah

Obadiah

c. 607

—

—

Ezekiel

Ezekiel

c. 591

613–c. 591

Babylon

1 and 2 Kings

Jeremiah

580

c. 1040-580

Judah/Egypt

Jeremiah

Jeremiah

580

647-580

Judah/Egypt

Daniel

Daniel

c. 536

618–c. 536

Babylon

Haggai

Haggai

520

112 days (520)

Jerusalem

Zechariah

Zechariah

518

520-518

Jerusalem

Esther

Mordecai

c. 475

493–c. 475

Shushan, Elam

1 and 2 Chronicles

Ezra

c. 460

After 1 Chronicles 9:44, 1077-537

Jerusalem (?)

Ezra

Ezra

c. 460

537–c. 467

Jerusalem

Psalms

David and others

c. 460

—

—

Nehemiah

Nehemiah

a. 443

456–a. 443

Jerusalem

Malachi

Malachi

a. 443

—

Jerusalem

[Chart on page 310]

Christian Greek Scriptures (C.E.)

Book

Writer

Date Completed

Time Covered

Place Written

Matthew

Matthew

c. 41

2 B.C.E.–33 C.E.

Palestine

1 Thessalonians

Paul

c. 50

—

Corinth

2 Thessalonians

Paul

c. 51

—

Corinth

Galatians

Paul

c. 50-52

—

Corinth or Syr. Antioch

1 Corinthians

Paul

c. 55

—

Ephesus

2 Corinthians

Paul

c. 55

—

Macedonia

Romans

Paul

c. 56

—

Corinth

Luke

Luke

c. 56-58

3 B.C.E.–33 C.E.

Caesarea

Ephesians

Paul

c. 60-61

—

Rome

Colossians

Paul

c. 60-61

—

Rome

Philemon

Paul

c. 60-61

—

Rome

Philippians

Paul

c. 60-61

—

Rome

Hebrews

Paul

c. 61

—

Rome

Acts

Luke

c. 61

33–c. 61 C.E.

Rome

James

James

b. 62

—

Jerusalem

Mark

Mark

c. 60-65

29-33 C.E.

Rome

1 Timothy

Paul

c. 61-64

—

Macedonia

Titus

Paul

c. 61-64

—

Macedonia (?)

1 Peter

Peter

c. 62-64

—

Babylon

2 Peter

Peter

c. 64

—

Babylon (?)

2 Timothy

Paul

c. 65

—

Rome

Jude

Jude

c. 65

—

Palestine (?)

Revelation

John

c. 96

—

Patmos

John

John

c. 98

After prologue, 29-33 C.E.

Ephesus, or near

1 John

John

c. 98

—

Ephesus, or near

2 John

John

c. 98

—

Ephesus, or near

3 John

John

c. 98

—

Ephesus, or near