Extinct Four-Eyed Monitor Lizard Busts Myth of a Congruent Nested Hierarchy

Günter Bechly

Günter Bechly

One of the most essential doctrines of Darwinian evolution, apart from universal common descent with modification, is the notion that complex similarities indicate homology and are ordered in a congruent nested pattern that facilitates the hierarchical classification of life. When this pattern is disrupted by incongruent evidence, such conflicting evidence is readily explained away as homoplasies with ad hoc explanations like underlying apomorphies (parallelisms), secondary reductions, evolutionary convergences, long branch attraction, and incomplete lineage sorting.

When I studied in the 1980s at the University of Tübingen, where the founder of phylogenetic systematics, Professor Willi Hennig, was teaching a first generation of cladists, we still all thought that such homoplasies are the exceptions to the rule, usually restricted to simple or poorly known characters. Since then the situation has profoundly changed. Homoplasy is now recognized as a ubiquitous phenomenon (e.g., eyes evolved 45 times independently, and bioluminiscence 27 times; hundreds of more examples can be found at Cambridge University’s “Map of Life” website).

Life’s Solution

This state of affairs compelled George McGhee, a paleobiology professor at Rutgers University, to write a book, Convergent Evolution: Limited Forms Most Beautiful (2011). He suggests that convergence is so common because viable forms are so limited. However, he fails to explain how evolution manages to find these limited solutions over and over again through a random search process. After all, selection only explains the survival of the fittest but not the arrival of the fittest.

Likewise, paleontologist Simon Conway Morris wrote two books, Life’s Solution (2003) and The Runes of Evolution (2015), in which he concluded that the incredible number of convergences came to be because evolution is not the contingent process postulated by Stephen Jay Gould (1989) in his book Wonderful Life. Gould thought that if we could somehow rewind the tape of evolution, everything would develop very differently. According to Conway Morris, the same novelties occur so often in unrelated groups that this suggests these novelties are not products of mere contingency but instead are so constrained by external factors that rewinding the tape of evolution would lead to very similar results (also see Conway Morris 2009 ).

Of course, Darwinists are not comfortable with the deeper implications of a non-contingent process of evolution (Ruse 2004, Coyne 2012, 2015), which smacks of being designed for a purpose. Apart from that, most biologists do not even read between the lines that this is basically a surrender of a fundamental paradigm of Darwinism, which claimed that similar biological novelties suggest phylogenetic relationship (common ancestry).

The problem gets worse the more we learn about the fossil record, the distribution of characters among recent organisms, and the genetic and developmental underpinnings of many characters. Some taxonomists had hoped that genomics might save biosystematics from the evil of homoplasy, since the sheer amount of data would flood the “minor” noise of homoplasies. But this turned out to be a pipe dream as the numerous conflicting molecular phylogenies easily document. Even those genetic characters that were believed to be impossible to suffer from convergence, like transposable elements, turned out to be incongruent (e.g., in the case of the gorilla, chimp, and human trichotomy), which required a whole new epicycle of ad hoc explanation in terms of incomplete lineage sorting.

The Third Eye

The third eye of vertebrates provides a perfect illustration of this point, topped by a very surprising recent discovery reviewed below. What, a third eye? I am neither talking about New Age spiritualism, nor about the cyclops of ancient Greek mythology, but about a little known light-sensing organ.

Unpaired median dorsal eyes, along with a lateral pair of more efficient eyes, are known from crustaceans (nauplius eye), arthropods (e.g., 3 ocelli in insects), and vertebrates (third eye, pineal eye, or parietal eye on the top of the skull). The latter is always smaller than the paired lateral lens eyes, and in living species very inconspicuous. Evolutionists believe this organ to be possibly homologous to the light-sensitive spot on top of the head of lancelets, and the median eye of tunicate larvae, because phylogenetic studies suggested that tunicates are the closest relatives of vertebrates, which are sometimes supposed to have originated from a kind of neotenic tunicate larva.

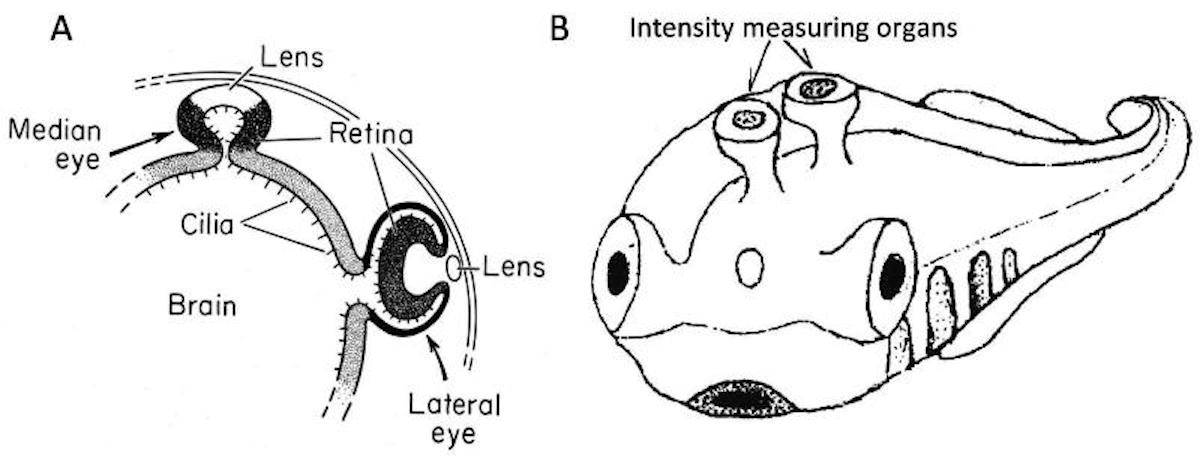

All vertebrate eyes, paired lateral as well as unpaired median ones, develop from an evagination of the brain (diencephalon). The posterior part of the diencephalon (epithalamus) develops an initially single dorsal evagination (pineal complex), which then divides into two roughly bilaterally symmetric organs that rotate their location to become a caudal pineal organ (pineal gland) and a rostral parapineal organ (Kolb et al. 1998). These often retain a slight asymmetry with the pineal organ originating more right and the parapineal organ more left of the brain midline.

This corresponds with the fact that modern lampreys possess two median eyes that are either oriented on top of each other or behind each other, while some Devonian fish (e.g., arthrodira, stegoselachians, and very early lungfish) had two pineal/parietal foramina in the skull beside each other (Eakin 1973: 16-17). In modern aquatic jawed vertebrates (“fish” in everyday language), the third eye, if developed at all, is formed by the pineal organ, while the parapineal organ is more or less reduced.

In tetrapods, the caudal pineal organ is atrophied as a still photoreceptive pineal gland (epiphysis), while the rostral parapineal organ forms the third eye called the parietal eye. Among recent vertebrates the parietal eye is absent in salamanders, turtles, crocs, birds, and mammals, but very well developed in lepidosaurs (juvenile tuataras and many lizards) with a lens, cornea, and an everted retina, with the latter being more similar to that of an octopus rather than to the inverted retina of the lateral lens eyes.

In juvenile frogs and toads a similar, but less sophisticated third eye develops as a terminal vesicle of the parapineal organ.hese third eyes in vertebrates do not allow image-like vision but only differentiate light from dark. They may help in detecting shadows from predators attacking from above, as suggested by the behavior of some lizards. More importantly they are crucial for circadian and seasonal rhythms. This also happens to be the function of the pineal gland in humans, which produces the sleep hormone melatonin. Many other vertebrate species have an intracranial pineal organ as deep-brain photoreceptor. In fossil vertebrates, the possession of an extracranial third eye can be inferred from the presence of a parietal foramen between the parietal bones of the skull.

Therefore, we have a pretty good knowledge about the distribution of third eyes in fossil and modern vertebrates. Here is a list of the haves and have nots:

lampreys, but not the blind hagfish

Paleozoic agnathan fish like ostracoderms and placoderms

pelagic sharks

some ray-finned fish (e.g., Paleozoic stem actinopterygians, paddlefish, catfish, tuna, and even the blind cave fish Astyanax mexicanus)

fossil “crossopterygians,” but not the modern coelacanth

early fossil lungfish, but not all modern ones

lobe-finned and “stegocephalian” stem tetrapods (e.g., Eusthenopteron, Elpistostege, Panderichthys, Tiktaalik, Acanthostega, Seymouria)

stem amphibians (Temnospondyli) and modern juvenile frogs and toads (Anura), but not salamanders (Urodela) and caecilians (Gymnophiona)

stem reptiles (e.g., Paleothyris)

Parareptilia (Anapsida like Captorhinus)

Lepidosauria (well visible in tuatara juveniles, mosasaurs, monitor lizards, iguanas, true lizards), but not snakes, geckos, and chameleons

Ichthyopterygia (ichthyosaurs)

Sauropterygia (placodontians, nothosaurs, plesiosaurs)

the oldest and most primitive stem turtle, Eunotosaurus, but not any later turtles (including Pappochelys)

early archosauromorphs like Prolacerta, proterosuchids, and arguably Triopticus primus, but not any more advanced archosauriforms (incl. Euparkeria, Phytosauria, crocodiles, pterosaurs, dinosaurs, and birds)

Permian mammal-like reptiles (“pelycosaurs,” “therapsids,” Cynognathia), but not any mammals (including Triassic primitive mammaliaforms like Morganucodon)

Guess what evolutionists must assume? Based on the just mentioned distribution of pineal and parapineal eyes and the parietal foramen: primitive agnathan vertebrates had two median eyes formed by the pineal and parapineal organ. These were retained at least up to the early ancestors of lungfish (documented by their paired parietal foramen), but the parapineal eye was independently reduced in Chondrichthyes (sharks and rays), ray-finned fish, coelacanths, and modern lungfish. In most modern bony fish (including ray-finned fish, coelacanths, and some modern lungfish) the pineal eye was reduced multiple times independently. In the tetrapod lineage the pineal eye was reduced as well, and only the parapineal eye retained as the parietal eye. This parietal eye was then reduced independently in non-anuran amphibians, some lizards, snakes, turtles, archosaurs (crocodiles, pterosaurs, dinosaurs, birds), and in mammals.

Consequently, only juvenile frogs and toads and well as juvenile tuataras and many lizards retained a parapineal parietal eye among living land vertebrates. What a wild ride. And all along the way, the magic wand of natural selection allegedly explains why the same organ appears and disappears and reappears, because it gains adaptive value and loses it, and gains it again. Not convinced? Neither am I. But the biggest surprise is yet to come.

Fasten Your Seatbelts, Please

Clearly, the presence or absence of a third eye in vertebrates shows an extremely incongruent pattern. Evolutionists need to explain away this incongruence. Since most groups of Paleozoic vertebrates had a third parietal eye, evolutionists have to assume that many different groups of vertebrates independently “decided” after the Permo-Triassic mass extinction that they could simply dispense with this previously so useful and adaptive innovation. Therefore, evolutionists need not only the ad hoc assumption of multiple independent secondary reductions, but also a causal explanation for this strange phenomenon.

Suggested explanations include reduced color vision correlated with freshwater habitat, or nocturnal lifestyle, or a transition to endothermia (Gerkema et al. 2013, Benoit et al. 2016, Emerling 2017a)

. Nocturnality as an explanation would indeed agree with the fact that the third eye is absent in the nocturnal geckos and in snakes, which are believed to have originated from a nocturnal burrowing ancestor, and that it is only prominent in juvenile tuataras, which have a diurnal lifestyle, while it is obliterated in adults, which have a nocturnal lifestyle. However, that two different causal explanations (nocturnal bottleneck versus transition to endothermia) have been suggested for the reduction of the parietal eyes in mammals shows that we are actually dealing with contrived ad hoc explanations. Whatever the data might be, a fancy narrative could easily be forged to explain this evidence.

Emerling (2017a) demonstrated that the photosensitive opsin proteins parietopsin and parapinopsin, found in the third eye of lampreys and lizards, are only present as nonfunctional pseudogenes in turtles, crocodiles, and birds, which all lack a third eye (Caspermeyer 2017).

To be fair, remnants of broken genes (pseudogenes), if they should truly be devoid of function (many ID proponents would predict this to be false), may indeed lend some support to the notion of common ancestry and a secondary reduction of the third eye in these groups. This was readily emphasized by Emerling (2017b), who clearly seems to have an evolutionary axe to grind, at his personal blog Evolution for Skeptics.

However, he admitted in his technical paper that these pseudogenes in turtles, crocodiles, and birds actually do not share inactivating mutations, so that the inactivation cannot be easily attributed to a common archelosaurian ancestor. This is at least strange for crocs and birds, because even their assumed archosauriform ancestors already shared the absence of a parietal eye, so that the inactivation should be expected to be homologous. Apart for this issue, merely appealing to common ancestry and multiple secondary reduction of course does nothing to explain what really is going on.

Emerling is aware of this and therefore suggested a nocturnal bottleneck in crocodylians as a causal explanation for their loss of the parietal eye. However, there is no evidence at all for such a bottleneck in the archosaur stem line, and this is fatal for his argument because it is not just crocodylians but all archosaurs that lack a parietal eye and its opsins, so that a nocturnal bottleneck in crocs would be totally irrelevant and much too late to explain anything. This also shows that the shared endothermia of birds and mammals is no good explanation for their shared lack of the parietal eye and its opsins either, because birds are believed to have ultimately originated from archosaurs that already lacked a parietal eye but were not endothermic at all. Most of the ad hoc explanations that may seem plausible at first sight thus become rather dubious at closer examination.

A Much Bigger Problem

Anyway, a much bigger problem for Darwinism arises from independent (homoplastic) gains of complex characters, rather than independent losses, especially when highly implausible evolutionary scenarios are implied. Here is a recent example for this that also involves the median eyes of vertebrates.

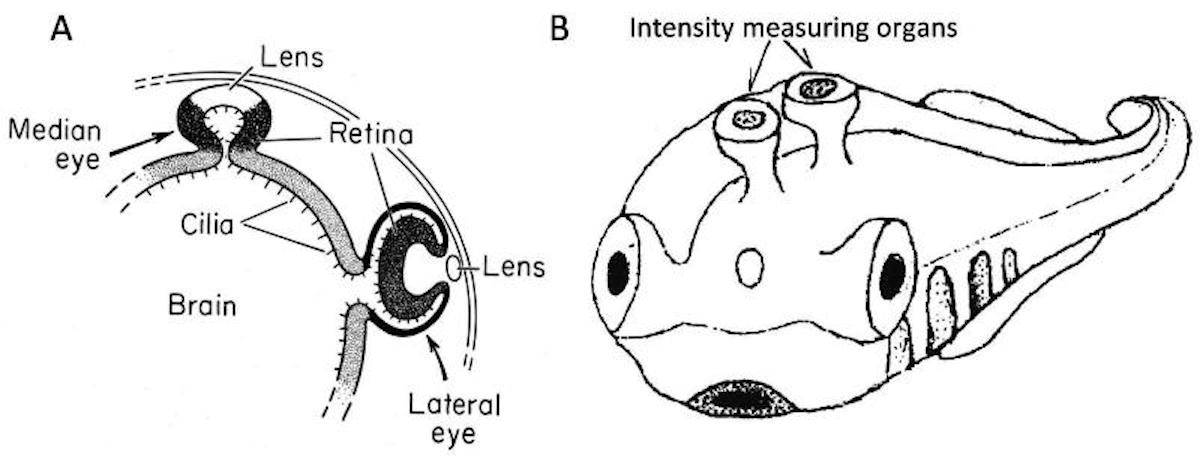

Based on two fragmentary fossils, Smith et al. (2018)

just described the new monitor lizard Saniwa ensidens from the 49 million year old Bridger Formation in Wyoming. Both known specimens surprisingly had four eyes! Additional to the normal pair of lateral lens eyes, and the usual parietal third eye of lizards, this new species actually had a forth pineal eye like a lamprey. Not a single other jawed vertebrate has something remotely like this, even though this fossil lizard is the closest relative of the modern monitor lizard genus Varanus and thus deeply nested within modern land vertebrates.

What? This sounds almost too weird to be true. Yet since the article was published on April 2, 2018, in the prestigious journal Current Biology it is definitely not an April Fools’ prank. The authors bite the bullet and boldly propose that the extinct monitor lizard re-evolved a fourth eye from the pineal organ, similar to the assumed ancestral state in lampreys. This means that even though a pineal eye was at least lost since the origin of tetrapods about 390 million years ago, 340 million years later just another ordinary species of monitor lizards came along and said, “Hey, what about having four eyes again?” It then re-evolved this organ that was obviously not of any sufficient adaptive value to any other tetrapod in the history of life to let evolution’s unlimited creative power do its magic. Nevertheless, this remarkable effort did not save this species from extinction without any surviving descendants, while numerous monitor lizards without fouth eye were more lucky.

In his review of the surprising discovery Witmer (2018) notes:

How could a pineal eye simply re-evolve? … But why Saniwa? What’s special about this lizard? Nothing is special, as far as we can tell. Smith and colleagues offer some suggestions, but it’s fair to say that the functional benefit of having both parapineal and pineal eyes remains obscure. This finding also means that all of a sudden we’re no longer sure which organ — pineal or parapineal eye — was peeking through the parietal foramen of a host of extinct ancient tetrapods.

In 1893, Belgian paleontologist Louis Dollo formulated the Law of the Irreversibility of Evolution, which simply states: that which is lost shall not be regained. Some laws are meant to be broken, and the re-evolution of a pineal eye in Saniwa is not the first atavism to be reported. Still, it’s not a common occurrence, and it’s so rare in this case that it raises new questions.

Obviously, evolutionary “laws” are quite malleable and have to give way when they become too cumbersome. Conflicting evidence does not matter, broken laws do not matter. What really matters is preserving the great narrative of pond scum to us.

We can safely conclude: it is an epic myth, willingly perpetuated by evolutionary biologists, that the similarities between organisms mostly fall in a hierarchic pattern of nested groups and thus suggest common ancestry and indicate phylogenetic relationship. In reality this claim is contradicted by a flood of incongruences and reticulate patterns that shed doubt on fundamental paradigms of evolutionary biology like the notions of homology and common descent. This inconvenient conflicting evidence is explained away with a pile of ad hoc hypotheses, correlated with more and more contrived and implausible evolutionary scenarios.

Literature:

- Benoit J, Abdala F, Manger PR, Rubidge BS 2016. The sixth sense in mammalian forerunners: Variability of the parietal foramen and the evolution of the pineal eye in South African Permo-Triassic eutheriodont therapsids. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 61 (4): 777–789.

- Caspermeyer J 2017. How Turtles and Crocodiles Lost the Parietal “Third” Eye and Their Differing Color Vision Adaptations. Molecular Biology and Evolution 34(3), 776–777.

- Conway Morris S 2003. Life’s Solution: Inevitable Humans in a Lonely Universe. Cambridge Univ. Press, 464 pp.

- Conway Morris S 2009. Evolution: like any other science it is predictable. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 365, 133–145.

- Conway Morris S 2015. The Runes of Evolution. Templeton Press, 528 pp.

- Coyne J 2012. Paleobiologist Simon Conway Morris gives evidence for God from evolution. Why Evolution is True September 10, 2012.

- Coyne J 2015. Simon Conway Morris’s new book once again claims that the evolution of human-like creatures was inevitable. He’s wrong. Why Evolution is True May 3, 2015.

- Eakin RM 1973. The Third Eye. University of California Press, 157 pp.

- Emerling CA 2017a. Archelosaurian color vision, parietal eye loss, and the crocodylian nocturnal bottleneck. Molecular Biology and Evolution 34(3), 666–676.

- Emerling CA 2017b. Turtles, birds and crocodylians have genetic remnants of a ‘third eye’. Evolution for Skeptics June 16, 2017.

- Gerkema MP, Davies WIL, Foster RH, Menaker M, Hut RA 2013. The nocturnal bottleneck and the evolution of activity patterns in mammals. Proceedings of the Royal Society B 280: 20130508.

- Gould SJ 1989. Wonderful Life. The Burgess Shale and the Nature of History. W.W. Norton Co.

- Kolb H, Fernandez E, Nelson R (eds) 1995. Webvision – The Organization of the Retina and Visual System. University of Utah Health Sciences Center, Internet book.

- McGhee GR 2011. Convergent Evolution: Limited Forms Most Beautiful. MIT Press, 336 pp.

- Ruse M 2004. Book Review 2: Life’s Solution: Inevitable Humans in a Lonely Universe. Palaeontologia Electronica 2:3.

- Smith KT, Bhullar BAS, Köhler G, Habersetzer J 2018. The Only Known Jawed Vertebrate with Four Eyes and the Bauplan of the Pineal Complex. Current Biology 28, 1101–1107.

- University of Cambridge. Map of Life — Convergent Evolution Online.

- Witmer LM 2018. Paleoneurology: A Sight for Four Eyes. Current Biology 28: R311-R313.