the bible,truth,God's kingdom,JEHOVAH God,New World,JEHOVAH Witnesses,God's church,Christianity,apologetics,spirituality.

Sunday, 15 July 2018

From doubt to dilemma re:the Cambrian explosion.

Newly Identified Banded Iron Formation Puts Origins Theories on Horns of a Dilemma

Evolution News | @DiscoveryCSC

Evolution News | @DiscoveryCSC

If you follow the attempts to stave off the design implications of what Stephen Meyer calls Darwin’s Doubt, you’re likely to be familiar with the oxygen theory of the Cambrian explosion. See here, here, and here for discussion of this and other competing proposals. The idea is that the explosion of new animal forms in the enigmatic Cambrian event could not have taken place earlier because the Earth’s oxygen levels were too low to allow it.

When the oxygen rose, this permitted animal life, thus authoring the biological information needed to fuel the design of trilobites and all the remarkable menagerie of new animal life from minimal (or seemingly non-existent) ancestral forms.

The Obvious Rebuttal

Even to state the idea clearly is to understand how ridiculous it is. The obvious rebuttal is that oxygen doesn’t design body plans. But a new study undercuts the oxygen theory at another level, and with a twist.

From a report at Science Daily, “Scientists discover Earth’s youngest banded iron formation in western China”:

The banded iron formation, located in western China, has been conclusively dated as Cambrian in age. Approximately 527 million years old, this formation is young by comparison to the majority of discoveries to date. The deposition of banded iron formations, which began approximately 3.8 billion years ago, had long been thought to terminate before the beginning of the Cambrian Period at 540 million years ago….

The Early Cambrian is known for the rise of animals, so the level of oxygen in seawater should have been closer to near modern levels. “This is important as the availability of oxygen has long been thought to be a handbrake on the evolution of complex life, and one that should have been alleviated by the Early Cambrian,” says Leslie Robbins, a [University of Alberta] PhD candidate in [Kurt] Konhauser’s lab and a co-author on the paper.

Remove the “handbrake” and we’re all set for the debut of animals. Their paper is published in Scientific Reports. What’s it all about?

Banded iron formations (BIFs) are much more common prior to about 2 billion years ago. The standard theory — that these “distinctive units of sedimentary rock…are almost always of Precambrian age,” according to Wikipeida

says that the Earth’s early oceans were rich in iron, and BIFs are supposed to indicate that the atmosphere had low oxygen content. That’s because they show oxygen was reacting with iron and precipitating out in ocean sediments instead of building up in the atmosphere. So this find of a Cambrian-, not Precambrian-aged BIF in China is very significant for at least two reasons. Together they land proponents of the oxygen theory, and advocates of materialist theories of the origin of life, on the horns of a painful dilemma.

So Much for the Oxygen Theory

As noted, many claim the Cambrian explosion was triggered by a sudden global increase in oxygen levels. We’ve discussed this many times, observing over and over that oxygen doesn’t generate new genetic information. But such information had to be the proximal cause of the Cambrian explosion. If we take the standard theory about BIFs seriously, then this new evidence ought to indicate that oxygen was LOW in the Cambrian, not high. This Chinese BIF contradicts all claims that there was high atmospheric oxygen in the Cambrian. So much for the oxygen theory.

On the Other Hand

Alternatively, however, maybe oxygen was HIGH in the Cambrian in which case BIFs don’t necessarily indicate low oxygen in the atmosphere. But if that is the case, origin-of-life theorists lose one of their favorite arguments that the Earth’s early atmosphere lacked oxygen in the Archean Eon.

A lack of oxygen in the Archaean atmosphere is important to generating prebiotic organics on the early Earth. If oxygen was present, then there is no viable mechanism for prebiotic synthesis. One of the main arguments for a lack of oxygen in the Earth’s early atmosphere is the presence of BIFs in the geological record of the Archean Eon and the Paleoproterozoic Era, or prior to about 2 billion years ago. But if BIFs can coexist with a high oxygen atmosphere, that argument falls to pieces.

Take your pick. A paradigm open to intelligent design can accommodate either option. For materialists, though, it’s a “Heads you win, tails I lose” situation.

Saturday, 14 July 2018

A rare victory for religious liberty.

Righting a Wrong for Conscientious Objectors: Long-Awaited Ruling by South Korea Constitutional Court

For some 65 years, young Christian men in South Korea have faced the certain prospect of imprisonment for their conscientious objection to military service. On Thursday, June 28, 2018, a landmark ruling by the Constitutional Court changed that prospect by declaring Article 5, paragraph 1, of the Military Service Act unconstitutional because the government makes no provision for alternative service.The nine-judge panel, headed by Chief Justice Lee Jin-sung, announced the 6-3 decision, which moves the country more in line with international norms and recognizes freedoms of conscience, thought, and belief.

South Korea has annually imprisoned more conscientious objectors than all other countries combined. At one point, an average of 500 to 600 of our brothers went to prison every year. Upon their release, all conscientious objectors carried with them a lifelong stigma due to their criminal record, which among other challenges limited their employment opportunities.

Starting in 2011, however, some brothers filed complaints with the Constitutional Court because the law provided no option other than imprisonment for their stand of conscience. Likewise, since 2012, even some judges who were troubled by the practice of punishing sincere objectors decided to refer their cases to the Constitutional Court for review of the Military Service Act.The role of the Constitutional Court is to determine if a law harmonizes with Korea’s Constitution or not. After having twice ruled (in 2004 and 2011) to uphold the Military Service Act, the Constitutional Court has finally agreed that change is needed. The Court ordered the government of South Korea to rewrite the law to include an alternative service option by the end of 2019. Alternative types of service that they may implement could include hospital work and other non-military social services that contribute to the betterment of the community.

Putting the decision in perspective, Brother Hong Dae-il, a spokesman for Jehovah’s Witnesses in Korea, states: “The Constitutional Court, which is the ultimate stronghold for protecting human rights, has provided a foundation for resolving this issue. Our brothers look forward to serving their community by means of alternative civilian service that does not conflict with their conscience and is in line with international standards.”

Other important issues await settlement, including the status of the 192 Witness objectors currently imprisoned and some 900 criminal cases pending in various levels of the courts.

The historic decision of the Constitutional Court provides a firmer basis for the Supreme Court to rule favorably in cases of individual objectors. A full bench ruling of the Supreme Court will influence how these individual criminal cases should be handled.

The Supreme Court is expected to hold a public hearing on August 30, 2018, and will issue a ruling some time thereafter. It will be the first time in 14 years that the Supreme Court’s full bench will review the issue of conscientious objection.

Meanwhile, the National Assembly, Korea’s legislature, is already working on revisions to the Military Service Act.

Brother Mark Sanderson of the Governing Body states: “We keenly anticipate the Supreme Court’s upcoming hearing. Our Korean brothers willingly sacrificed their freedom, knowing that ‘it is agreeable when someone endures hardship and suffers unjustly because of conscience toward God.’ (1 Peter 2:19) We rejoice with them that the injustice they endured has finally been recognized, along with their courageous stand of conscience.”

Jehovah's swag appears to be a problem for purveyors of scientism

Psychologists Say "Awe" in the Face of Nature Is a Problem for Science

David Klinghoffer

This almost seems like a parody, but it's not. Researchers at Claremont McKenna, Yale, and Berkeley sound an alarm about the peril in experiencing awe when we're confronted with nature and its wonders. They warn in particular that this should be "disconcerting to those interested in promoting an accurate understanding of evolution."

Abstract from the journal Emotion, where the research appears, summarizes:

Past research has established a relationship between awe and explanatory frameworks, such as religion. We extend this work, showing (a) the effects of awe on a separate source of explanation: attitudes toward science, and (b) how the effects of awe on attitudes toward scientific explanations depend on individual differences in theism. Across 3 studies, we find consistent support that awe decreases the perceived explanatory power of science for the theistic (Study 1 and 2) and mixed support that awe affects attitudes toward scientific explanations for the nontheistic (Study 3).

You mean all those splendid David Attenborough nature documentaries actually undermine a Darwinian view rather than, as intended, reinforcing it?

Dr. Douglas Axe, protein scientist and author of Undeniable: How Biology Confirms Our Intuition That Life Is Designed, hits the nail on the head over at The Stream:

All those jaw-dropping nature documentaries have been messing with our minds.

Most wildlife shows are packaged with the usual Darwinian narrative, spoken in an authoritative tone that isn't supposed to be questioned. But it seems that wildlife itself, in stunning visual display, is conveying a different message -- more powerfully, in fact.

Everyone is awed by life, and experiences that accentuate this awe seem to affect us, whether or not we believe in God. The new study suggests that these experiences affirm a sense of faith in theists and a sense of purpose-like natural order in atheists and agnostics, both of which cause problems for instructors wanting to churn out good Darwinists.

An Awful Blind Spot

Maybe "good" isn't the right word there. I mean, if something as obviously good for science as awe works against a "scientific" idea, wouldn't that suggest this idea isn't really so good or scientific in first place? How good can a way of viewing life be if excitement about life undermines it?

Common sense provides the clearest take-home message here. Since awe and wonder have always drawn people to scientific exploration, any form of teaching that calls for policing those emotions can't possibly be in the best interest of science.

As clear as that seems, the people who did the study don't see it that way. This is a perfect case of academic researchers being so constrained by their materialistic worldview -- so convinced that the physical world is all there is -- that they can't see the implications of their own work clearly.

Read the rest.

If we could take a pill that dulled the sense of wonder, would these psychology professors recommend it? If awe is a problem that stands in the way of science -- meaning atheism -- it's hard to see why not. Perhaps, to put an end to that deplorable intelligent design nonsense once and for all, let's prescribe it for kids along with their Ritalin.

David Klinghoffer

This almost seems like a parody, but it's not. Researchers at Claremont McKenna, Yale, and Berkeley sound an alarm about the peril in experiencing awe when we're confronted with nature and its wonders. They warn in particular that this should be "disconcerting to those interested in promoting an accurate understanding of evolution."

Abstract from the journal Emotion, where the research appears, summarizes:

Past research has established a relationship between awe and explanatory frameworks, such as religion. We extend this work, showing (a) the effects of awe on a separate source of explanation: attitudes toward science, and (b) how the effects of awe on attitudes toward scientific explanations depend on individual differences in theism. Across 3 studies, we find consistent support that awe decreases the perceived explanatory power of science for the theistic (Study 1 and 2) and mixed support that awe affects attitudes toward scientific explanations for the nontheistic (Study 3).

You mean all those splendid David Attenborough nature documentaries actually undermine a Darwinian view rather than, as intended, reinforcing it?

Dr. Douglas Axe, protein scientist and author of Undeniable: How Biology Confirms Our Intuition That Life Is Designed, hits the nail on the head over at The Stream:

All those jaw-dropping nature documentaries have been messing with our minds.

Most wildlife shows are packaged with the usual Darwinian narrative, spoken in an authoritative tone that isn't supposed to be questioned. But it seems that wildlife itself, in stunning visual display, is conveying a different message -- more powerfully, in fact.

Everyone is awed by life, and experiences that accentuate this awe seem to affect us, whether or not we believe in God. The new study suggests that these experiences affirm a sense of faith in theists and a sense of purpose-like natural order in atheists and agnostics, both of which cause problems for instructors wanting to churn out good Darwinists.

An Awful Blind Spot

Maybe "good" isn't the right word there. I mean, if something as obviously good for science as awe works against a "scientific" idea, wouldn't that suggest this idea isn't really so good or scientific in first place? How good can a way of viewing life be if excitement about life undermines it?

Common sense provides the clearest take-home message here. Since awe and wonder have always drawn people to scientific exploration, any form of teaching that calls for policing those emotions can't possibly be in the best interest of science.

As clear as that seems, the people who did the study don't see it that way. This is a perfect case of academic researchers being so constrained by their materialistic worldview -- so convinced that the physical world is all there is -- that they can't see the implications of their own work clearly.

Read the rest.

If we could take a pill that dulled the sense of wonder, would these psychology professors recommend it? If awe is a problem that stands in the way of science -- meaning atheism -- it's hard to see why not. Perhaps, to put an end to that deplorable intelligent design nonsense once and for all, let's prescribe it for kids along with their Ritalin.

In case you missed it:Evolution is a fact.

Here, Evidently, Is How They Teach Evolution at Louisiana State University

David Klinghoffer | @d_klinghoffer

David Klinghoffer | @d_klinghoffer

If you want a taste of how and by whom evolutionary biology is being taught to college students, check this out. Prosanta Chakrabarty is an ichthyologist at Louisiana State University, and says of himself that he teaches “one of the largest evolutionary biology classes in the U.S.” Good for him, and I don’t doubt that’s true.

But this has got to be one of the dopiest, most simple-minded presentations of the subject that I’ve seen.

“It’s a Fact”

Professor Chakrabarty informs us:

[W]e’re taught to say “the theory of evolution.” There are actually many theories, and just like the process itself, the ones that best fit the data are the ones that survive to this day. The one we know best is Darwinian natural selection. That’s the process by which organisms that best fit an environment survive and get to reproduce, while those that are less fit slowly die off. And that’s it. Evolution is as simple as that, and it’s a fact. Evolution is a fact as much as the “theory of gravity.” You can prove it just as easily. You just need to look at your belly button that you share with other placental mammals, or your backbone that you share with other vertebrates, or your DNA that you share with all other life on earth. Those traits didn’t pop up in humans. They were passed down from different ancestors to all their descendants, not just us.

The sufficiency of Darwin’s theory of natural selection for explaining the history of life is “as simple as” the observation that animals that can’t survive in their environment, don’t survive. “It’s a fact” because you have a belly button, in common with other placental mammals.

By the same token, my car has four wheels, two axles, and runs on gasoline, like other gas-powered cars stretching back well over a century. Car models that no one wants to buy ultimately cease to be manufactured. It must be that the Ford Model T and the Volvo S70 and everything in between all “evolved” by unguided natural selection from a common ancestor. Remember, it’s a fact. Only the foolish religious fundamentalist would consider that engineering had anything to do with it.

A Long History

The comparison of evolution with gravity also has a long history, about as long as the history of automobiles. Maybe it evolved, too. See Granville Sewell, “Why Evolution is More Certain than Gravity.” Also, “I Believe in the Evolution of Life and the Evolution of Automobiles.”

Professor Chakrabarty speaks with what I take to be a weary, ill-concealed contempt for those don’t understand these matters. He teaches in the same state where the Louisiana Science Education Act was passed a little over ten years ago,and remains the law. If this is how evolution is taught to college students at LSU, imagine how it’s taught to many high school students.

Do you wonder, then, that educators, parents, and other residents of the state sought, under the LSEA, protection from retaliatory action for teachers who wish to add a bit of depth, some critical weighing of the evidence, to their instruction?

Darwinism and the search for the master race.

Evolutionary Psychology Grapples with Racism and Anti-Semitism

Richard Weikart

Richard Weikart

When I published my book From From Darwin to Hitler: Evolutionary Ethics, Eugenics, and Racism in Germany (2004), I had no idea that white nationalism and neo-Nazism would become more fashionable in the coming years. At that time white nationalism was a fringe movement that one heard very little about, and the term “alt-right” had not even been coined yet.

Some of my critics informed me that the historical links I drew between Darwinism and racism or Darwinism and Nazism were misguided, because most Darwinian biologists today are firmly anti-racist and anti-Nazi. I never quite understood why the views of current Darwinian biologists were relevant to my argument, however, because I was not arguing that Darwinism inevitably produces Nazism. I was making a more modest and less assailable historical point: Nazis embraced Darwinism and used it as a foundational principle of their worldview. (I proved this in even greater detail in Hitler’s Ethic: The Nazi Pursuit of Evolutionary Progress.)

Recycling Racial Ideas

However, ironically, the recent upsurge of white nationalism and the alt-right has actually made my historical case more plausible. Not only do many of the leading figures in this movement, such as Richard Spencer, embrace Darwinism with alacrity, but they recycle many of the racial ideas of the late 19th and early 20th centuries that I discuss in From Darwin to Hitler.

They argue that races are unequal, because they have evolved differently. Of course, conveniently they have discovered that their own ancestors — white Europeans — have evolved greater intellectual capacities than other races.

These racist ideas are still taboo in mainstream academe — as they should be. When the Nobel Prize-winning biologist James Watson suggested in 2007 that some racial groups, such as black Africans, had lower intelligence because of their evolutionary history, he faced outrage and sustained criticism.

Worrying Signs

However, some worrying signs are emerging that the taboo may be cracking. The journal Evolutionary Psychological Science, which has eminent evolutionary psychologists, such as Harvard’s Steven Pinker, on its editorial board, recently carried an article defending the anti-Semitic, racist views of Kevin MacDonald, a white supremacist and emeritus professor of psychology at California State University, Long Beach.

MacDonald’s views are eerily similar to those of scientists I examine in my historical scholarship: racial groups are in a human struggle for existence, behavioral traits are biologically innate, and stereotypical Jewish traits are evolutionary strategies for beating other races in racial competition. MacDonald claims that anti-Semitism is a defensive strategy to help white Europeans and their descendants triumph over the Jews.

Darwin and many early Darwinists saw racism and human inequality as part and parcel of their theory. MacDonald is trying to resurrect this troubling legacy of Darwinian theory.

To kill a zombie.

New Book on "Junk DNA" Surveys the Functions of Non-Coding DNA

Casey Luskin

What Discovery Institute biologist Jonathan Wells calls the "myth of junk DNA," long a favorite with advocates of unguided evolution, isn't yet quite dead and buried. You still see it invoked in popular science media. Last month in The New York Times Magazine, Carl Zimmer defended the notion that our genome is mostly garbage, earning cheers from evolutionary advocates like PZ Myers and Lawrence Moran, the latter hailing Zimmer as the "best science journalist on the planet." We devoted some attention to Zimmer's article (see here andhere). But for many scientists, "junk DNA" is an idea that is increasingly untenable in light of the empirical data.

A new book from Columbia University Press, Junk DNA: A Journey Through the Dark Matter of the Genome, by virologist Nessa Carey provides a detailed review of the vast evidence being uncovered showing function for "junk DNA." She explains that junk DNA was initially "dismissed" by biologists because it was thought that if it didn't code for proteins, it didn't do anything:

For years, scientists had no explanation for why so much of our DNA doesn't code for proteins. These non-coding parts were dismissed with the term "junk DNA." But gradually this position has begun to look less tenable, for a whole host of reasons. (p. 2)

Of course in dismissing non-coding "junk" DNA, we must conclude that these same evolutionary scientists hindered research into its function.

Now Carey gives no indication that she's an ID proponent and in fact she adopts many standard evolutionary viewpoints within her book. But note how, in making her case that we ought to suspect non-coding DNA has function, she employs a curious analogy. She draws a comparison to a car factory -- something that obviously is intelligently designed:

Perhaps the most fundamental reason for the shift in emphasis is the sheer volume of junk DNA that our cells contain. One of the biggest shocks when the human genome sequence was completed in 2001 was the discovery that over 98 per cent of the DNA in a human is junk. It doesn't code for any proteins. ...

...Let's imagine we visit a car factory, perhaps for something high-end like a Ferrari. We would be pretty surprised if for every two people who were building a shiny red sports car, there were another 98 who were sitting around doing nothing. This would be ridiculous, so why would it be reasonable in our genomes? ...

...A much more likely scenario in our car factory would be that for every two people assembling a car, there are 98 others, doing all the things that keeps a business moving. Raising finances, keeping accounts, publicizing the product, processing the pensions, cleaning the toilets, selling the cars etc. This is probably a much better model for the role of junk in our genome. We can think of proteins as the final end points required for life, but they will never be properly produced and coordinated without the junk. Two people can build a car, but they can't maintain a company selling it, and certainly can't turn it into a powerful and financially successful brand. Similarly, there's no point having 98 people mopping the floors and staffing the showrooms if there's nothing to sell. The whole organization only works when all the components are in place. And so it is with our genomes. (p. 3)

Don't miss that last line: "The whole organization only works when all the components are in place. And so it is with our genomes." Doesn't that sound exactly like irreducible complexity? So here we have a biologist, unaffiliated with the intelligent-design community, arguing that junk DNA must be functional because it's like a car factory where all the components are needed in order for the entire system to function. Critics might claim that ID has had no impact on biological thinking, but the evidence shows otherwise.

Before moving on I must make a point about terminology. At the beginning of the book, Carey notes that when she uses the term "junk DNA," she does so to describe any stretch of non-coding DNA, and doesn't necessarily mean something that has no function. "Anything that doesn't code for a protein will be described as junk, as it originally was in the old days (second half of the twentieth century)," she writes. Thus, she's not affirmatively claiming the piece of "junk DNA" doesn't have function. Rather, she's referring to a type of DNA that was once thought to be functionless "junk," and now is most likely thought to have function.

Carey, in any event, goes on to explain how today we now believe that, far from being irrelevant, it's the "junk DNA" that is running the whole show:

The other shock from the sequencing of the human genome was the realisation that the extraordinary complexities of human anatomy, physiology, intelligence and behaviour cannot be explained by referring to the classical model of genes. In terms of numbers of genes that code for proteins, humans contain pretty much the same quantity (around 20,000) as simple microscopic worms. Even more remarkably, most of the genes in the worms have directly equivalent genes in humans.

As researchers deepened their analyses of what differentiates humans from other organisms at the DNA level, it became apparent that genes could not provide the explanation. In fact, only one genetic factor generally scaled with complexity. The only genomic features that increased in number as animals became more complicated were the regions of junk DNA. The more sophisticated an organism, the higher the percentage of junk DNA it contains. Only now are scientists really exploring the controversial idea that junk DNA may hold the key to evolutionary complexity. (p. 4)

Of course by "evolutionary complexity," what Carey means is genomic functionality. She goes on to spend the bulk of the book reviewing the numerous discoveries of function for non-coding "junk" DNA. Just a few of those include:

Structural roles such as packaging chromosomes and preventing DNA "from unravelling and becoming damaged," acting as "anchor points when chromosomes are shared equally between different daughter cells and during cell division," and serving as "insulation regions, restricting gene expression to specific regions of chromosomes."

Regulating gene expression, as "Thousands and thousands of regions of junk DNA are suspected to regulate networks of gene expression."

Introns are extremely important:

The bits of gobbledygook between the parts of a gene that code for amino acids were originally considered to be nothing but nonsense or rubbish. They were referred to as junk or garbage DNA, and pretty much dismissed as irrelevant. ... But we now know that they can have a very big impact. (pp. 17-18)

Preventing mutations by separating out gene-coding DNA.

Controlling telomere length that can serve as a "molecular clock" that helps control aging.

Forming the loci for centromeres.

Activating X chromosomes in females.

Producing long non-coding RNAs which regulate Hox genes or regulating brain development, or serving as attachment points for histone-modifying enzymes helping to turn genes on and off.

Serving as promoters or enhancers for genes, or imprinting control elements for "the expression of the protein-coding genes."

Producing RNA which acts "as a kind of scaffold, directing the activity of proteins to particular regions of the genome."

Producing RNAs which can fold into three-dimensional shapes and perform functions inside cells, much like enzymes, changing the shapes of other molecules, or helping to build ribosomes. As she notes: "We've actually known about these peculiar RNA molecules for decades, making it yet more surprising that we have maintained such a protein-centric vision of our genomic landscape." (p. 146)

Serving as tRNA genes which produce tRNA molecules. These genes can also serve as insulators or spacers to stop transcription from spreading from gene to gene.

Development of the fingers and face; changing eye, skin, and hair color; affecting obesity.

Gene splicing and generating spliceosomes.

Producing small RNAs which also affect gene expression.

The ENCODE Project as "Evolutionary Battleground"

Carey rightly calls the ENCODE project (Encyclopedia of DNA Elements) an "evolutionary battleground." That's because it claimed that some 80 percent of our genome is functional, a finding that some evolutionary biologists have vigorously disputed. Of course ENCODE's findings are based upon empirical data, and evolutionary objections are based upon theoretical concerns. That's why evolutionary biologists find ENCODE so threatening to their models. Though Carey doesn't mention this, Dan Graur said, "If ENCODE is right, then evolution is wrong." What's going on here?

The main evolutionary response, as Carey explains, is that "only about 5 percent of the human genome is conserved across the mammalian class." Since evolutionary biologists assume that a structure is only functional if it's under selection, non-conserved sequences suggest a sequence is not under selection pressure. Hence, they assume all that DNA can't be functional.

Carey provides a very good response to this argument, which I'll get to in a moment. But from an ID perspective there's an immediate rebuttal that is obvious: If we abandon the assumption that natural selection alone can generate functional elements in our genome, then we're freed up to consider that perhaps many functional elements of mammalian genomes did not arise by selection but were designed separately with distinct DNA sequences from the very beginning. That would result in the exact sort of data that ENCODE is revealing -- vast quantities of non-conserved functional genetic elements -- that is vexing evolutionary biologists. Indeed, other previous studies have revealed non-conserved DNA that has specific functions. As Jonathan Wells explains:

But while sequence conservation may imply function, non-conservation does not imply non-function -- as biologists have long recognized. Indeed, to whatever extent DNA differences play a role in distinguishing different species, non-conserved sequences must be functional.

Furthermore, biologists now know that as much as 30 percent of the protein-coding DNA in every organism consists of "orphan genes" that bear little or no similarity to DNA sequences in other organisms. While the functions of most orphan proteins are not yet known, few people would be so foolhardy as to suggest that they are non-functional. Yet in a search for evolutionary constraint such as the Oxford researchers used, these protein-coding regions would be judged non-functional.

Carey provides another intriguing hypothesis -- that even from an evolutionary perspective many functional genetic elements may be under relaxed selection for DNA sequence. She writes:

Protein-coding sequences are highly conserved in evolution because a particular protein is often used in more than one tissue or cell type. If the protein changed in sequence, the altered protein might function better in a particular tissue. But that same change might have a really damaging effect in another tissue that relies on the same protein. This acts as an evolutionary pressure that maintains protein sequence.

But regulatory RNAs, which don't code for proteins, tend to be more tissue-specific. Therefore they are under less evolutionary pressure because only one tissue relies on a regulatory RNA, and possibly only during certain periods of life or in response to certain environmental changes. This has removed the evolutionary brakes on the regulatory RNAs and allowed us to diverge from our mammalian cousins in these regions. (p. 195)

Her argument makes sense: genetic elements that interact with fewer aspects of an organism's genome, transcriptome, proteome, and other physiological components, might face fewer sequence-constraints than those that maybe have only one such interaction. Evolutionary biologists tend to assume that selection works the same in all physiological contexts, but if that's not true, then we could see relaxed selection allowing genetic elements to be functional and non-conserved.

Carey notes that ENCODE critics, namely evolutionary biologists, reacted harshly to ENCODE's claims that the vast majority of our genome is functional (pp. 196-197):

The most forthright responses were mainly from evolutionary biologists. This wasn't altogether surprising. Evolution is the biological discipline where emotions tend to run highest. Normally the bullets are targeted at creationists, but the Gatling guns may also be turned on other scientists. ... The angriest critique of ENCODE included the expressions "logical fallacy," "absurd conclusion," "playing fast and loose" and "used the wrong definition wrongly." Just in case we were still in doubt about their direction of travel, the authors concluded the paper with the following damning blast:

The ENCODE results were predicted by one of its lead authors to necessitate the rewriting of textbooks. We agree, many textbooks dealing with marketing, mass media hype, and public relationships may well have to be rewritten.

She notes: "There are interesting scientific arguments on both sides, but it would be disingenuous to believe that the amount of heat and emotion generated by ENCODE has been purely about the science. We can't ignore other, very human factors." (p. 198)

In any case, I suspect that Carey herself holds an even more pro-ENCODE view than her book lets on, and what we see may be a toned-down version of what she really thinks. She seems to be diplomatically trying to avoid the "emotional" attacks of angry evolutionary biologists who stridently oppose ENCODE.

Much Research Remains to Be Completed

Carey doesn't openly take a side in the debate over ENCODE, and she doesn't claim that our genome will eventually turn out to contain no "junk" DNA whatsoever. But she is clear that the trend line in research is away from junk DNA, and she notes that one reason for our lack of understanding of what a lot of junk DNA does is that we haven't yet developed the technologies to study it:

Part of the problem is that the systems we can use to probe the functions of junk DNA are still relatively underdeveloped. This can sometimes make it hard for researchers to use experimental approaches to test their hypotheses. We have only been working on this for a relatively short space of time. (p. 6)

In other words, it's very premature to conclude that our genome is full of truly functionless junk DNA. Lacking the technology to detect function, it's understandable why we might have missed a lot of the important functions going on in the genome.

As Carey notes, "We now know that in some cases just a single base-pair change in an apparently irrelevant region of the genome can have a definite effect" (p. 201), meaning there's a lot of work left to be done. After all, she points out: "One stretch of DNA can include a protein-coding gene, long non-coding RNAs, small RNAs, antisense RNAs, splice signal sites, untranslated regions, promoters and enhancers." (p. 287) Thus, she concludes, "When we really think about the complexity of our genomes, it isn't surprising that we can't understand everything yet." (p. 288) And that, along with much else in this excellent book, hits the nail on the head.

For years, scientists had no explanation for why so much of our DNA doesn't code for proteins. These non-coding parts were dismissed with the term "junk DNA." But gradually this position has begun to look less tenable, for a whole host of reasons. (p. 2)

Of course in dismissing non-coding "junk" DNA, we must conclude that these same evolutionary scientists hindered research into its function.

Now Carey gives no indication that she's an ID proponent and in fact she adopts many standard evolutionary viewpoints within her book. But note how, in making her case that we ought to suspect non-coding DNA has function, she employs a curious analogy. She draws a comparison to a car factory -- something that obviously is intelligently designed:

Perhaps the most fundamental reason for the shift in emphasis is the sheer volume of junk DNA that our cells contain. One of the biggest shocks when the human genome sequence was completed in 2001 was the discovery that over 98 per cent of the DNA in a human is junk. It doesn't code for any proteins. ...

...Let's imagine we visit a car factory, perhaps for something high-end like a Ferrari. We would be pretty surprised if for every two people who were building a shiny red sports car, there were another 98 who were sitting around doing nothing. This would be ridiculous, so why would it be reasonable in our genomes? ...

...A much more likely scenario in our car factory would be that for every two people assembling a car, there are 98 others, doing all the things that keeps a business moving. Raising finances, keeping accounts, publicizing the product, processing the pensions, cleaning the toilets, selling the cars etc. This is probably a much better model for the role of junk in our genome. We can think of proteins as the final end points required for life, but they will never be properly produced and coordinated without the junk. Two people can build a car, but they can't maintain a company selling it, and certainly can't turn it into a powerful and financially successful brand. Similarly, there's no point having 98 people mopping the floors and staffing the showrooms if there's nothing to sell. The whole organization only works when all the components are in place. And so it is with our genomes. (p. 3)

Don't miss that last line: "The whole organization only works when all the components are in place. And so it is with our genomes." Doesn't that sound exactly like irreducible complexity? So here we have a biologist, unaffiliated with the intelligent-design community, arguing that junk DNA must be functional because it's like a car factory where all the components are needed in order for the entire system to function. Critics might claim that ID has had no impact on biological thinking, but the evidence shows otherwise.

Before moving on I must make a point about terminology. At the beginning of the book, Carey notes that when she uses the term "junk DNA," she does so to describe any stretch of non-coding DNA, and doesn't necessarily mean something that has no function. "Anything that doesn't code for a protein will be described as junk, as it originally was in the old days (second half of the twentieth century)," she writes. Thus, she's not affirmatively claiming the piece of "junk DNA" doesn't have function. Rather, she's referring to a type of DNA that was once thought to be functionless "junk," and now is most likely thought to have function.

Carey, in any event, goes on to explain how today we now believe that, far from being irrelevant, it's the "junk DNA" that is running the whole show:

The other shock from the sequencing of the human genome was the realisation that the extraordinary complexities of human anatomy, physiology, intelligence and behaviour cannot be explained by referring to the classical model of genes. In terms of numbers of genes that code for proteins, humans contain pretty much the same quantity (around 20,000) as simple microscopic worms. Even more remarkably, most of the genes in the worms have directly equivalent genes in humans.

As researchers deepened their analyses of what differentiates humans from other organisms at the DNA level, it became apparent that genes could not provide the explanation. In fact, only one genetic factor generally scaled with complexity. The only genomic features that increased in number as animals became more complicated were the regions of junk DNA. The more sophisticated an organism, the higher the percentage of junk DNA it contains. Only now are scientists really exploring the controversial idea that junk DNA may hold the key to evolutionary complexity. (p. 4)

Of course by "evolutionary complexity," what Carey means is genomic functionality. She goes on to spend the bulk of the book reviewing the numerous discoveries of function for non-coding "junk" DNA. Just a few of those include:

Structural roles such as packaging chromosomes and preventing DNA "from unravelling and becoming damaged," acting as "anchor points when chromosomes are shared equally between different daughter cells and during cell division," and serving as "insulation regions, restricting gene expression to specific regions of chromosomes."

Regulating gene expression, as "Thousands and thousands of regions of junk DNA are suspected to regulate networks of gene expression."

Introns are extremely important:

The bits of gobbledygook between the parts of a gene that code for amino acids were originally considered to be nothing but nonsense or rubbish. They were referred to as junk or garbage DNA, and pretty much dismissed as irrelevant. ... But we now know that they can have a very big impact. (pp. 17-18)

Preventing mutations by separating out gene-coding DNA.

Controlling telomere length that can serve as a "molecular clock" that helps control aging.

Forming the loci for centromeres.

Activating X chromosomes in females.

Producing long non-coding RNAs which regulate Hox genes or regulating brain development, or serving as attachment points for histone-modifying enzymes helping to turn genes on and off.

Serving as promoters or enhancers for genes, or imprinting control elements for "the expression of the protein-coding genes."

Producing RNA which acts "as a kind of scaffold, directing the activity of proteins to particular regions of the genome."

Producing RNAs which can fold into three-dimensional shapes and perform functions inside cells, much like enzymes, changing the shapes of other molecules, or helping to build ribosomes. As she notes: "We've actually known about these peculiar RNA molecules for decades, making it yet more surprising that we have maintained such a protein-centric vision of our genomic landscape." (p. 146)

Serving as tRNA genes which produce tRNA molecules. These genes can also serve as insulators or spacers to stop transcription from spreading from gene to gene.

Development of the fingers and face; changing eye, skin, and hair color; affecting obesity.

Gene splicing and generating spliceosomes.

Producing small RNAs which also affect gene expression.

The ENCODE Project as "Evolutionary Battleground"

Carey rightly calls the ENCODE project (Encyclopedia of DNA Elements) an "evolutionary battleground." That's because it claimed that some 80 percent of our genome is functional, a finding that some evolutionary biologists have vigorously disputed. Of course ENCODE's findings are based upon empirical data, and evolutionary objections are based upon theoretical concerns. That's why evolutionary biologists find ENCODE so threatening to their models. Though Carey doesn't mention this, Dan Graur said, "If ENCODE is right, then evolution is wrong." What's going on here?

The main evolutionary response, as Carey explains, is that "only about 5 percent of the human genome is conserved across the mammalian class." Since evolutionary biologists assume that a structure is only functional if it's under selection, non-conserved sequences suggest a sequence is not under selection pressure. Hence, they assume all that DNA can't be functional.

Carey provides a very good response to this argument, which I'll get to in a moment. But from an ID perspective there's an immediate rebuttal that is obvious: If we abandon the assumption that natural selection alone can generate functional elements in our genome, then we're freed up to consider that perhaps many functional elements of mammalian genomes did not arise by selection but were designed separately with distinct DNA sequences from the very beginning. That would result in the exact sort of data that ENCODE is revealing -- vast quantities of non-conserved functional genetic elements -- that is vexing evolutionary biologists. Indeed, other previous studies have revealed non-conserved DNA that has specific functions. As Jonathan Wells explains:

But while sequence conservation may imply function, non-conservation does not imply non-function -- as biologists have long recognized. Indeed, to whatever extent DNA differences play a role in distinguishing different species, non-conserved sequences must be functional.

Furthermore, biologists now know that as much as 30 percent of the protein-coding DNA in every organism consists of "orphan genes" that bear little or no similarity to DNA sequences in other organisms. While the functions of most orphan proteins are not yet known, few people would be so foolhardy as to suggest that they are non-functional. Yet in a search for evolutionary constraint such as the Oxford researchers used, these protein-coding regions would be judged non-functional.

Carey provides another intriguing hypothesis -- that even from an evolutionary perspective many functional genetic elements may be under relaxed selection for DNA sequence. She writes:

Protein-coding sequences are highly conserved in evolution because a particular protein is often used in more than one tissue or cell type. If the protein changed in sequence, the altered protein might function better in a particular tissue. But that same change might have a really damaging effect in another tissue that relies on the same protein. This acts as an evolutionary pressure that maintains protein sequence.

But regulatory RNAs, which don't code for proteins, tend to be more tissue-specific. Therefore they are under less evolutionary pressure because only one tissue relies on a regulatory RNA, and possibly only during certain periods of life or in response to certain environmental changes. This has removed the evolutionary brakes on the regulatory RNAs and allowed us to diverge from our mammalian cousins in these regions. (p. 195)

Her argument makes sense: genetic elements that interact with fewer aspects of an organism's genome, transcriptome, proteome, and other physiological components, might face fewer sequence-constraints than those that maybe have only one such interaction. Evolutionary biologists tend to assume that selection works the same in all physiological contexts, but if that's not true, then we could see relaxed selection allowing genetic elements to be functional and non-conserved.

Carey notes that ENCODE critics, namely evolutionary biologists, reacted harshly to ENCODE's claims that the vast majority of our genome is functional (pp. 196-197):

The most forthright responses were mainly from evolutionary biologists. This wasn't altogether surprising. Evolution is the biological discipline where emotions tend to run highest. Normally the bullets are targeted at creationists, but the Gatling guns may also be turned on other scientists. ... The angriest critique of ENCODE included the expressions "logical fallacy," "absurd conclusion," "playing fast and loose" and "used the wrong definition wrongly." Just in case we were still in doubt about their direction of travel, the authors concluded the paper with the following damning blast:

The ENCODE results were predicted by one of its lead authors to necessitate the rewriting of textbooks. We agree, many textbooks dealing with marketing, mass media hype, and public relationships may well have to be rewritten.

She notes: "There are interesting scientific arguments on both sides, but it would be disingenuous to believe that the amount of heat and emotion generated by ENCODE has been purely about the science. We can't ignore other, very human factors." (p. 198)

In any case, I suspect that Carey herself holds an even more pro-ENCODE view than her book lets on, and what we see may be a toned-down version of what she really thinks. She seems to be diplomatically trying to avoid the "emotional" attacks of angry evolutionary biologists who stridently oppose ENCODE.

Much Research Remains to Be Completed

Carey doesn't openly take a side in the debate over ENCODE, and she doesn't claim that our genome will eventually turn out to contain no "junk" DNA whatsoever. But she is clear that the trend line in research is away from junk DNA, and she notes that one reason for our lack of understanding of what a lot of junk DNA does is that we haven't yet developed the technologies to study it:

Part of the problem is that the systems we can use to probe the functions of junk DNA are still relatively underdeveloped. This can sometimes make it hard for researchers to use experimental approaches to test their hypotheses. We have only been working on this for a relatively short space of time. (p. 6)

In other words, it's very premature to conclude that our genome is full of truly functionless junk DNA. Lacking the technology to detect function, it's understandable why we might have missed a lot of the important functions going on in the genome.

As Carey notes, "We now know that in some cases just a single base-pair change in an apparently irrelevant region of the genome can have a definite effect" (p. 201), meaning there's a lot of work left to be done. After all, she points out: "One stretch of DNA can include a protein-coding gene, long non-coding RNAs, small RNAs, antisense RNAs, splice signal sites, untranslated regions, promoters and enhancers." (p. 287) Thus, she concludes, "When we really think about the complexity of our genomes, it isn't surprising that we can't understand everything yet." (p. 288) And that, along with much else in this excellent book, hits the nail on the head.

Saturday, 7 July 2018

1914: Why is it a marked year?:The Bible's answer.

What Does Bible Chronology Indicate About the Year 1914?

The Bible’s answer:

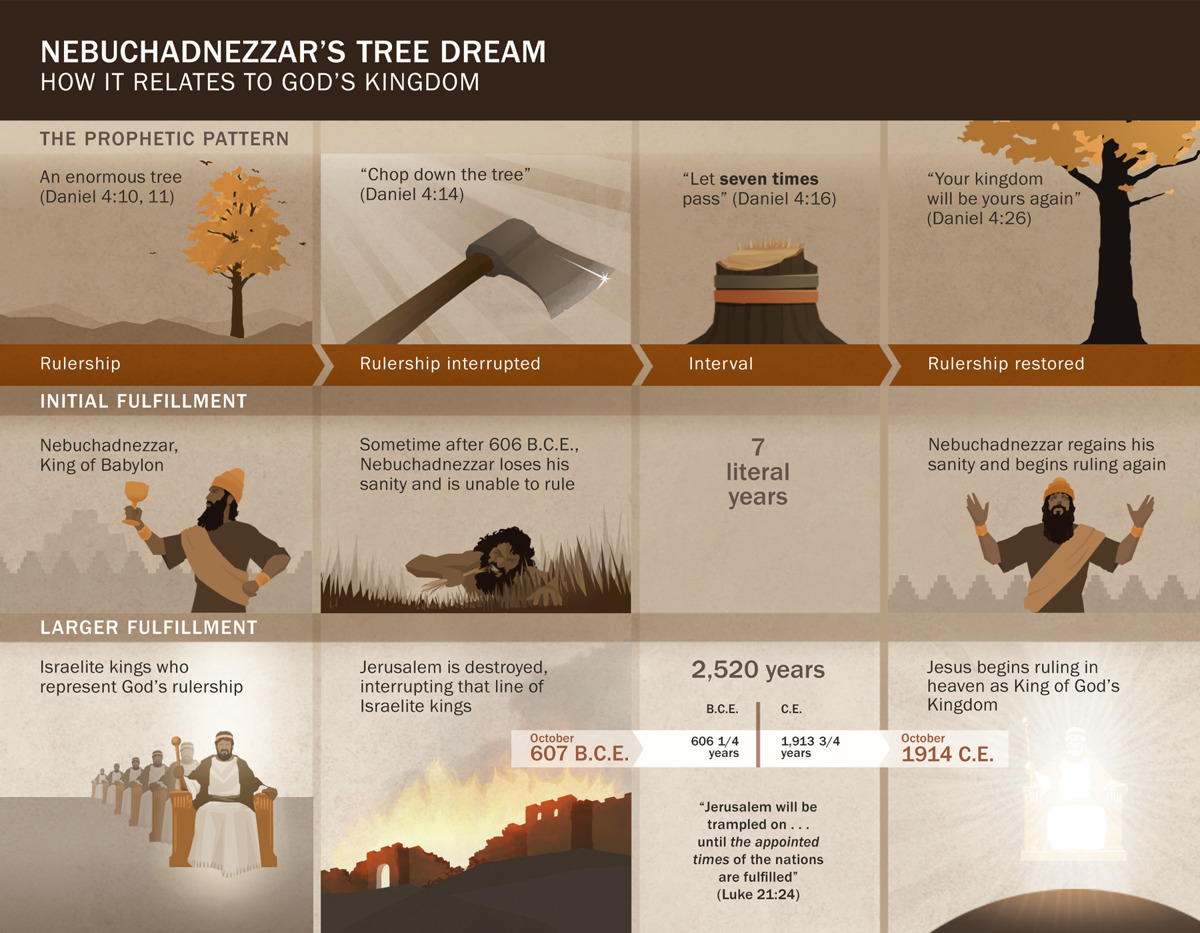

Bible chronology indicates that God’s Kingdom was established in heaven in 1914. This is shown by a prophecy recorded in chapter 4 of the Bible book of Daniel.

Overview of the prophecy. God caused King Nebuchadnezzar of Babylon to have a prophetic dream about an immense tree that was chopped down. Its stump was prevented from regrowing for a period of “seven times,” after which the tree would grow again.—Daniel 4:1, 10-16.

The prophecy’s initial fulfillment. The great tree represented King Nebuchadnezzar himself. (Daniel 4:20-22) He was figuratively ‘chopped down’ when he temporarily lost his sanity and kingship for a period of seven years. (Daniel 4:25) When God restored his sanity, Nebuchadnezzar regained his throne and acknowledged God’s rulership.—Daniel 4:34-36.

Evidence that the prophecy has a greater fulfillment. The whole purpose of the prophecy was that “people living may know that the Most High is Ruler in the kingdom of mankind and that he gives it to whomever he wants, and he sets up over it even the lowliest of men.” (Daniel 4:17) Was proud Nebuchadnezzar the one to whom God ultimately wanted to give such rulership? No, for God had earlier given him another prophetic dream showing that neither he nor any other political ruler would fill this role. Instead, God would himself “set up a kingdom that will never be destroyed.”—Daniel 2:31-44.

Previously, God had set up a kingdom to represent his rulership on earth: the ancient nation of Israel. God allowed that kingdom to be made “a ruin” because its rulers had become unfaithful, but he foretold that he would give kingship to “the one who has the legal right.” (Ezekiel 21:25-27) The Bible identifies Jesus Christ as the one legally authorized to receive this everlasting kingdom. (Luke 1:30-33) Unlike Nebuchadnezzar, Jesus is “lowly in heart,” just as it was prophesied.—Matthew 11:29.

What does the tree of Daniel chapter 4 represent? In the Bible, trees sometimes represent rulership. (Ezekiel 17:22-24; 31:2-5) In the greater fulfillment of Daniel chapter 4, the immense tree symbolizes God’s rulership.

What does the tree’s being chopped down mean? Just as the chopping down of the tree represented an interruption in Nebuchadnezzar’s kingship, it also represented an interruption in God’s rulership on earth. This happened when Nebuchadnezzar destroyed Jerusalem, where the kings of Israel sat on “Jehovah’s throne” as representatives of God himself.—1 Chronicles 29:23.

What do the “seven times” represent? The “seven times” represent the period during which God allowed the nations to rule over the earth without interference from any kingdom that he had set up. The “seven times” began in October 607 B.C.E., when, according to Bible chronology, Jerusalem was destroyed by the Babylonians. *—2 Kings 25:1, 8-10.

How long are the “seven times”? They could not be merely seven years as in Nebuchadnezzar’s case. Jesus indicated the answer when he said that “Jerusalem [a symbol of God’s rulership] will be trampled on by the nations until the appointed times of the nations are fulfilled.” (Luke 21:24) “The appointed times of the nations,” the period during which God allowed his rulership to be “trampled on by the nations,” are the same as the “seven times” of Daniel chapter 4. This means that the “seven times” were still under way even when Jesus was on earth.

The Bible provides the way to determine the length of those prophetic “seven times.” It says that three and a half “times” equal 1,260 days, so “seven times” equal twice that number, or 2,520 days. (Revelation 12:6, 14) Applying the prophetic rule “a day for a year,” the 2,520 days represent 2,520 years. Therefore, the “seven times,” or 2,520 years, would end in October 1914.—Numbers 14:34; Ezekiel 4:6.

In the eye of the beholder?

You Can’t Climb a Mountain with Ostrich Legs

A post yesterday on the human oral cavity, a frequent target of taunts about “unintelligent design,” noted that the ability to speak clearly is had at the cost of a small danger of choking. Commenting on this, thoughtful reader Matthew makes a great point about the trade-offs that necessarily go along with intelligent design in biology. He refers to anatomist Alice Roberts and her stunt of designing a “Perfect Human Body,” which Jonathan Wells and Ann Gauger both wrote about earlier.

The only problem is that this imagined body isn’t and can’t be perfect. From “A Vision of the ‘Perfect’ Woman,” with some revealing comments by Dr. Roberts who chose ostrich over human legs:

LEGS: Our knees and feet are complex. Both are prone to damage, and failure. But there are more efficient ways of doing things. “If we focused on one thing, we could streamline the design. I’ve taken my inspiration from ostriches — which are bipedal, like us, but extremely good at running.”

Running is good, and avoiding injuries is excellent. But there’s a seemingly unavoidable trade-off:

“I traded agility for speed when I altered my legs and replaced my feet — and that means my chances of climbing a mountain are zero. But I think it’s worth it — even though I screamed when I saw the final 3D model of my creation,” she explained.

Alice Robert thinks trading human for ostrich legs is “worth it,” although thus equipped “my chances of climbing a mountain are zero.” What about swimming? That’s an interesting question that Dr. Gauger reflected on. Ostriches can bathe when it gets hot out but they have a hard time exiting a swimming pool without human assistance and if they get too far out to sea, they probably require rescue.

Exploring the Planet

Matthew’s insight: “The CURRENT design is the more efficient one that gives us the ability to use the entire planet.” Right! Humans are the only creatures that swim where we want, dive deep below the ocean surface, climb high mountains, plunge into deep subterranean caves, and run fast, thanks to the design of our legs (and arms) despite the trade-offs that come with it. Ostriches are fast, but they are not known for their scuba skills, or as mountaineers or spelunkers.

Compromises are driven by the limitations of a material world, but also by the vision that lies behind the design. The vision of Alice Roberts is comfortable with setting mountains out of reach of the “perfect” woman. However, it was apparently a priority for the intelligent agent behind our actual design that human beings should have the ability to explore the whole planet, just as the design of Earth itself and its place in the cosmos were evidently configured to permit human exploration.

You could get theological at this point, but there’s no need. Clearly, we were intended to discover our world, whether land, sea, or skies. The facts speak for themselves.

Sunday, 1 July 2018

And still yet more on the real world's anti Darwinian bias.

Fossil Turaco Is Yet Another Failed Biogeographical Prediction for Neo-Darwinism

Evolution News | @DiscoveryCSC

Evolution News | @DiscoveryCSC

In a delightful article here yesterday, German paleontologist Günter Bechly documents the many absurdities that result when the Darwinian teaching on universal common ancestry runs up against a consideration of the field of biogeography.

Bechly:

[I]t is far from true that biogeography unambiguously supports common ancestry, or that patterns of biogeographic distribution always align well with the pattern of reconstructed phylogenetic branching or the supposed age of origin. Indeed, there are many tenacious problems of biogeography and paleobiogeography that do not square well with the evolutionary paradigm of common descent.

His examples include ratite birds, freshwater snails, trapdoor snails, worm-lizards, iguanas and boine snakes, and more.

Enter the Banana-Eater

Here’s another little story, “Bird family tree shaken by discovery of feathered fossil,” that discusses an additional interesting biogeographical problem for neo-Darwinism. BBC News reports:

They’re some of the strangest birds in the world, known for their bright plumage and their penchant for fruit.

The turacos, or banana-eaters, are today found only in Africa, living in forests and savannah.

But now scientists have found the earliest known fossil of this bird group not in the Old World but in NORTH AMERICA — aged 52 million years!

Why Does That Matter?

It matters because at 52 million years ago, North America was completely separated from Africa by thousands of kilometers, with no land bridges in sight. See here for an idea of how the world is thought to have looked at this time.

Presumably they will just conclude that birds can get around due to their ability to fly great distances, and thus they can avoid another embarrassing appeal to monkeys and other animals “rafting” across the open Atlantic Ocean to solve this problem. But it’s still a further failed biogeographical prediction for neo-Darwinism.

The technical paper in BMC Evolutionary Biology, “A North American stem turaco, and the complex biogeographic history of modern birds,” by Daniel J. Field and Allison Y. Hsiang, is open access and can be found here.

It says:

Our analyses offer the first well-supported evidence for a stem musophagid (and therefore a useful fossil calibration for avian molecular divergence analyses), and reveal surprising new information on the early morphology and biogeography of this clade.

Where Is the Surprise?

The “new information” is “surprising” only if you rigidly insist on universal common ancestry where species are predicted to exist only in geographical locations that are easily reachable from where you think they originally evolved.

Evolutionists love to boast about the predictive power of their theory. But the paper states:

When informative branch length data are incorporated, the fossil record provides indispensable data on evolutionary and biogeographic history, leading to reconstructions that may be unexpected when one considers extant data alone.

In other words, ancient or fossil biogeographic locations of species don’t necessarily accord with modern day biogeographic locations of species. So on what basis can evolutionary theory make biogeographical predictions?

A better body?

The Perfect Human Body?

Jonathan Wells

Jonathan Wells

We all know that the human body can suffer from flaws. For most people, that doesn’t mean our bodies are accidental by-products of unguided evolution. Instead, they are designed — despite the fact that they sometimes start out flawed or become flawed as they grow older.

For English anatomist Alice Roberts, however, the human body is a “hodge-podge” of parts assembled in an “untidy” fashion “with no foresight” by evolution. So, like many evolutionary biologists before her, she set out with some colleagues to “design and build the Perfect Body.” Her results were aired on BBC Four on June 13, 2018.

According to Roberts, the Perfect Human Body would have ears like cats and lungs like birds. (Of course, bird lungs would require major modifications to other aspects of human anatomy, but the details might get “untidy.”)

The Perfect Human Body would also have legs like ostriches. Ostrich legs are “digitigrade” — they rest on their toes. They are also very fast, enabling ostriches to run very quickly on the plains of Africa. And ostrich legs have proven to be a good model for making prosthetics to help people whose legs have been amputated above the knee.

Human legs are “plantigrade” — they rest on their soles. They are not as good at running as digitigrade legs, but their stance is more stable and they are a lot more versatile. Would I trade mine for the equivalent of prosthetics worn by an amputee? Not unless I have to.

Another change Roberts would make is to the reproductive system. Because of the large size of a human baby’s head, giving birth can be dangerous and very painful for women — though modern medicine has made it much safer and less painful. For Roberts, it would have been better if humans had evolved to be marsupials, like kangaroos, whose tiny fetuses crawl out into a pouch to complete their development.

But marsupials are much less intelligent than placental mammals (which include not only humans, but also sloths), because a marsupial brain “differs markedly in both structure and bulk” from a placental brain. So Roberts’s Perfect Human would be much less intelligent than an actual human being.

But my favorite among her “improvements” is the eye. According to Roberts, “our eyes have evolved” such that

the retina is “backwards.” The light receptors are at the back; the nerve fibre “wires” take off at the front, and then have to converge on a spot where they pierce through and exit the eye — the optic disc — which creates a blind spot. Our brains fill in this blind spot so that we’re not aware of it. But how about we wire up the eye sensibly and avoid the blind spot in the first place. Octopi do just that — so let’s steal their anatomy for the eye.

As I’ve written several times before, this is a myth promoted by Darwinist Richard Dawkins and his followers — even though the evidence against it was already available in scientific publications before Dawkins invented it. The light-sensing cells in a human eye are so metabolically active that they must be nourished and maintained by a dense network of blood vessels and a specialized layer of epithelial cells. If the blood vessels and epithelial cells were between the light-sensing cells and the incoming light, we would be almost blind. By contrast, nerve cells are almost transparent. The so-called “backwards retina,” far from being poorly designed, seems to be optimally designed.

As for octopus eyes: Biologists have known for more than thirty years that octopus eyes are inferior to human eyes, because in human eyes the information from light-sensing cells is pre-processed by the nerve cells in the retina itself. Octopus eyes must transmit their visual information all the way to the brain to be processed into images. The result is fuzzier signals and slower processing. An octopus eye “is just a ‘passive’ retina which is able to transmit only information, dot by dot, coded in a far less sophisticated fashion than in vertebrates.”

Why do people enamored of evolution ignore the evidence and presume they can create the Perfect Human Body? Is this the way science is supposed to work?

Saturday, 30 June 2018

On Darwinism's loaded dice.

The Fallacy of Evolutionary Advantage

Evolution News | @DiscoveryCSC

Consider the following story:

Why are there two modes of transportation for accomplishing the same function? Bicycles and automobiles apparently emerged independently. While both provide transport, the automobile would seem to have a clear advantage in miles traveled per unit energy. Our analysis suggests a possible explanation for this apparent relationship between energy input and mechanism. When the car and the bicycle are traveling at about 10 kph, the ratio of energy expenditure per meter is about the same [for the sake of illustration]. When the conditions under which transport must occur at higher velocity are encountered, the gasoline engine mechanism may have been selected for its kinetic advantage. On the other hand, when conditions require a velocity of 10 kph or less, the foot-pedal mechanism may have been selected for other possible advantages resulting from its structural and functional simplicity.

We laugh at this silly tale, but evolutionists often employ this kind of reasoning very seriously: if something is advantageous, nature must have selected it! Since evolutionary theory forbids any appeal to intelligent causes, whatever scientists observe — no matter how intricate — must have been designed without a designer, and selected without a selector.

Here’s a recent example in PLOS ONE. Two scientists from the Department of Computational and Systems Biology at the University of Pittsburgh propounded the exact same reasoning as our story, except their machines are much smaller. But the same fallacy applies. In fact, we adapted our story from similar language in their paper, “Biophysical comparison of ATP-driven proton pumping mechanisms suggests a kinetic advantage for the rotary process depending on coupling ratio.” Notice the similarities:

ATP-driven proton pumps, which are critical to the operation of a cell, maintain cytosolic and organellar pH levels within a narrow functional range. These pumps employ two very different mechanisms: an elaborate rotary mechanism used by V-ATPase H+ pumps, and a simpler alternating access mechanism used by P-ATPase H+ pumps. Why are two different mechanisms used to perform the same function? Systematic analysis, without parameter fitting, of kinetic models of the rotary, alternating access and other possible mechanisms suggest that, when the ratio of protons transported per ATP hydrolyzed exceeds one, the one-at-a-time proton transport by the rotary mechanism is faster than other possible mechanisms across a wide range of driving conditions. When the ratio is one, there is no intrinsic difference in the free energy landscape between mechanisms, and therefore all mechanisms can exhibit the same kinetic performance. To our knowledge all known rotary pumps have an H+:ATP ratio greater than one, and all known alternating access ATP-driven proton pumps have a ratio of one. Our analysis suggests a possible explanation for this apparent relationship between coupling ratio and mechanism. When the conditions under which the pump must operate permit a coupling ratio greater than one, the rotary mechanism may have been selected for its kinetic advantage. On the other hand, when conditions require a coupling ratio of one or less, the alternating access mechanism may have been selected for other possible advantages resulting from its structural and functional simplicity. [Emphasis added.]

They are talking, mind you, about one of the most amazing molecular machines in all life: the ATP synthase rotary motor. We featured it in an animation. And as we have written about before, it comes in two types: the mitochondrial F0F1-ATPase that synthesizes ATP from a proton motive force, and the vacuolar V-ATPase that acidifies vacuoles with a similar mechanism running in reverse. Just to look at these machines in operation screams intelligent design!

The P-ATPase proton pump they refer to is no less awe-inspiring. Even though it uses a less-efficient mechanism (one proton per one ATP), it sustains critical cellular functions. The gills of young salmon, for instance, use the sodium-potassium pump (Na+/K+ P-ATPase) for adapting to seawater when exiting their natal streams, and use the pumps in reverse when returning. This animation shows that the design, while simpler than ATP synthase, is elegant and effective, like the bicycle compared to the car. Here at Evolution News, physician Howard Glicksman described the many important functions this pump accomplishes in the human body.

Now that we know about the two machines discussed in the PLOS ONE paper, do the authors ever describe how they arose by random mutations and natural selection? Of course not. To them, it’s sufficient to say, “They’re advantageous; therefore they evolved.” Full stop. In fact, the evolutionists double the miracle-working power of natural selection by saying this, fully aware of the complexity of these machines:

Two very distinct mechanisms, which most likely evolved independently, are employed for ATP-driven H+ pumps: the rotary mechanism of the V-ATPase and the alternating access mechanism used by the P-ATPases (Fig 1). The significantly more complex V-ATPase consists of 25–39 protein chains compared to a monomeric or homodimeric polypeptide for the P-ATPase. The operating mechanism for the V-ATPase is also more elaborate consisting of an electric motor-like rotary mechanism. In contrast, the P-ATPase operates by switching between two (E1 and E2) conformations similar to most allosteric mechanisms.

We should gasp at such credulity in a scientific paper. Yet the two authors, with two more colleagues, published a similar paper in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) last year: “Biophysical comparison of ATP synthesis mechanisms shows a kinetic advantage for the rotary process.” The same fallacy is central to their whole paper: “Our analysis shows that the rotary mechanism is faster than other possible mechanisms, particularly under challenging conditions, suggesting a possible evolutionary advantage.”

Why did evolution select two very different mechanisms for ATP-driven proton pumps? Here we explore one possible consideration: the difference in kinetics, i.e. the rate of H+ pumping, between the two mechanisms, building on our recent study of ATP synthesis kinetics [the PNAS paper]. A mechanism that can pump protons faster, under the same conditions (same bioenergetic cost), may be able to respond to cellular demands and changing conditions more rapidly. Also, a faster mechanism would require a lower driving potential (bioenergetic cost) to achieve the same pumping rate compared to a slower mechanism. Such a mechanism may offer a survival advantage particularly when the difference in rates is large and in a highly competitive environment. Presumably such a mechanism would be under positive selection pressure.

The authors don’t just waltz past these statements, as if to get on to more rigorous matters. No; the Evolutionary Advantage Fallacy is central to their whole thesis. We count the word advantage 25 times, usually in an evolutionary context: in particular, evolutionary advantage or selective advantage eight times. Here it is twice in the concluding discussion:

Why are there two different mechanisms, a rotary mechanism and an alternating access mechanism, for ATP-driven proton pumps? Many factors contribute to overall evolutionary fitness, and here we focus on kinetic behavior, which is amenable to systematic analysis…. These results suggest that when driving conditions are such that a coupling ratio above one is sufficient for viable operation, the rotary mechanism may have a selective advantage. However, when a process requires a coupling ratio of one for viable operation, the alternating access mechanism may have a selective advantage because of its simplicity and corresponding lower cost of protein synthesis.

Another case of the Evolutionary Advantage Fallacy appears in PNAS. Wei Lin and ten other international colleagues think that bacteria evolved magnetotaxis because it would have been advantageous to them. “The early origin for magnetotaxis would have provided evolutionary advantages in coping with environmental challenges faced by microorganisms on early Earth,” they say. Just because the “Archean geodynamo was sufficient to support magnetotaxis,” doesn’t mean that bacteria will create genes and behaviors to make use of it. That’s like saying water creates fish.

Are these isolated cases we’re picking on? A quick search on Google Scholar for “evolutionary advantage” yields over 32,000 hits. In our experience, this is a frequently used phrase that is usually devoid of any detailed description of how random mutations and natural selection could have achieved the said advantages. The simplistic syllogism, “It’s advantageous, therefore it evolved,” is not a scientific theory. It’s mere word salad.

Evolution News | @DiscoveryCSC

Consider the following story:

Why are there two modes of transportation for accomplishing the same function? Bicycles and automobiles apparently emerged independently. While both provide transport, the automobile would seem to have a clear advantage in miles traveled per unit energy. Our analysis suggests a possible explanation for this apparent relationship between energy input and mechanism. When the car and the bicycle are traveling at about 10 kph, the ratio of energy expenditure per meter is about the same [for the sake of illustration]. When the conditions under which transport must occur at higher velocity are encountered, the gasoline engine mechanism may have been selected for its kinetic advantage. On the other hand, when conditions require a velocity of 10 kph or less, the foot-pedal mechanism may have been selected for other possible advantages resulting from its structural and functional simplicity.

We laugh at this silly tale, but evolutionists often employ this kind of reasoning very seriously: if something is advantageous, nature must have selected it! Since evolutionary theory forbids any appeal to intelligent causes, whatever scientists observe — no matter how intricate — must have been designed without a designer, and selected without a selector.

Here’s a recent example in PLOS ONE. Two scientists from the Department of Computational and Systems Biology at the University of Pittsburgh propounded the exact same reasoning as our story, except their machines are much smaller. But the same fallacy applies. In fact, we adapted our story from similar language in their paper, “Biophysical comparison of ATP-driven proton pumping mechanisms suggests a kinetic advantage for the rotary process depending on coupling ratio.” Notice the similarities:

ATP-driven proton pumps, which are critical to the operation of a cell, maintain cytosolic and organellar pH levels within a narrow functional range. These pumps employ two very different mechanisms: an elaborate rotary mechanism used by V-ATPase H+ pumps, and a simpler alternating access mechanism used by P-ATPase H+ pumps. Why are two different mechanisms used to perform the same function? Systematic analysis, without parameter fitting, of kinetic models of the rotary, alternating access and other possible mechanisms suggest that, when the ratio of protons transported per ATP hydrolyzed exceeds one, the one-at-a-time proton transport by the rotary mechanism is faster than other possible mechanisms across a wide range of driving conditions. When the ratio is one, there is no intrinsic difference in the free energy landscape between mechanisms, and therefore all mechanisms can exhibit the same kinetic performance. To our knowledge all known rotary pumps have an H+:ATP ratio greater than one, and all known alternating access ATP-driven proton pumps have a ratio of one. Our analysis suggests a possible explanation for this apparent relationship between coupling ratio and mechanism. When the conditions under which the pump must operate permit a coupling ratio greater than one, the rotary mechanism may have been selected for its kinetic advantage. On the other hand, when conditions require a coupling ratio of one or less, the alternating access mechanism may have been selected for other possible advantages resulting from its structural and functional simplicity. [Emphasis added.]

They are talking, mind you, about one of the most amazing molecular machines in all life: the ATP synthase rotary motor. We featured it in an animation. And as we have written about before, it comes in two types: the mitochondrial F0F1-ATPase that synthesizes ATP from a proton motive force, and the vacuolar V-ATPase that acidifies vacuoles with a similar mechanism running in reverse. Just to look at these machines in operation screams intelligent design!