the bible,truth,God's kingdom,JEHOVAH God,New World,JEHOVAH Witnesses,God's church,Christianity,apologetics,spirituality.

Sunday, 21 May 2017

Ladybug v. Darwin.

Ladybug, Living Origami, Lends a Hand with Umbrella and Other Designs

David Klinghoffer | @d_klinghoffer

Delicate and delightful, ladybug beetles are the insect everyone loves. Having one unexpectedly land on your hand is a reminder of how gentle and beautiful nature can be.

Their ability to alternate nimbly between walking and flying is also a marvel of design. Japanese scientists have been working on clarifying the secret of how they fold and unfold their wings, an effortless gesture of living origami. They published their findings in PNAS.

From USA Today:

Japanese scientists were curious to learn how ladybugs folded their wings inside their shells, so they surgically removed several ladybugs’ outer shells (technically called elytra) and replaced them with glued-on, artificial clear silicone shells to peer at the wings’ underlying folding mechanism.

Why bother with such seemingly frivolous research? It turns out that how the bugs naturally fold their wings can provide design hints for a wide range of practical uses for humans. This includes satellite antennas, microscopic medical instruments, and even everyday items like umbrellas and fans.

“The ladybugs’ technique for achieving complex folding is quite fascinating and novel, particularly for researchers in the fields of robotics, mechanics, aerospace and mechanical engineering,” said lead author Kazuya Saito of the University of Tokyo. [Emphasis added.]

That is astonishingly wide array of “design hints” from the humble bug, which are also called ladybirds. See the design in action:The Telegraph echoes:

Ladybird wings could help change design of umbrellas for first time in 1,000 years

The New York Times:

Ladybugs Pack Wings and Engineering Secrets in Tidy Origami Packages

[…]

To the naked eye, this elegant transformation is a mystery. But scientists in Japan created a window into the process in a study published Monday in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Just how the ladybug manages to cram these rigid structures into tiny spaces is a valuable lesson for engineers designing deployable structures like umbrellas and satellites.

A ladybug’s hind wings are sturdy enough to keep it in the air for up to two hours and enable it to reach speeds up to 37 miles an hour and altitudes as high as three vertically stacked Empire State Buildings. Yet they fold away with ease. These seemingly contradictory attributes perplexed Kazuya Saito, an aerospace engineer at the University of Tokyo and the lead author of the study.

Working on creating deployable structures like large sails and solar power systems for spacecrafts, he turned to the ladybug for design inspiration.

Notice how, in discussing them, it’s as if we are forced to use the language of design. Regarding ladybugs and their “engineering secrets,” as the NY Times candidly puts it, molecular biologist Douglas Axe tweets:“Like a DeLorean, only cooler!” Here is a DeLorean:In his book Undeniable: How Biology Confirms Our Intuition That Life Is Designed, Dr. Axe uses the illustration of an origami crane. With good reason behind this universal intuition, our minds rebel at the idea that any origami creation could arise through a combination of chance and law, without purpose or design. Yet Darwinian theory demands that we believe a real crane arose that way, or a real ladybug.

David Klinghoffer | @d_klinghoffer

Delicate and delightful, ladybug beetles are the insect everyone loves. Having one unexpectedly land on your hand is a reminder of how gentle and beautiful nature can be.

Their ability to alternate nimbly between walking and flying is also a marvel of design. Japanese scientists have been working on clarifying the secret of how they fold and unfold their wings, an effortless gesture of living origami. They published their findings in PNAS.

From USA Today:

Japanese scientists were curious to learn how ladybugs folded their wings inside their shells, so they surgically removed several ladybugs’ outer shells (technically called elytra) and replaced them with glued-on, artificial clear silicone shells to peer at the wings’ underlying folding mechanism.

Why bother with such seemingly frivolous research? It turns out that how the bugs naturally fold their wings can provide design hints for a wide range of practical uses for humans. This includes satellite antennas, microscopic medical instruments, and even everyday items like umbrellas and fans.

“The ladybugs’ technique for achieving complex folding is quite fascinating and novel, particularly for researchers in the fields of robotics, mechanics, aerospace and mechanical engineering,” said lead author Kazuya Saito of the University of Tokyo. [Emphasis added.]

That is astonishingly wide array of “design hints” from the humble bug, which are also called ladybirds. See the design in action:The Telegraph echoes:

Ladybird wings could help change design of umbrellas for first time in 1,000 years

The New York Times:

Ladybugs Pack Wings and Engineering Secrets in Tidy Origami Packages

[…]

To the naked eye, this elegant transformation is a mystery. But scientists in Japan created a window into the process in a study published Monday in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Just how the ladybug manages to cram these rigid structures into tiny spaces is a valuable lesson for engineers designing deployable structures like umbrellas and satellites.

A ladybug’s hind wings are sturdy enough to keep it in the air for up to two hours and enable it to reach speeds up to 37 miles an hour and altitudes as high as three vertically stacked Empire State Buildings. Yet they fold away with ease. These seemingly contradictory attributes perplexed Kazuya Saito, an aerospace engineer at the University of Tokyo and the lead author of the study.

Working on creating deployable structures like large sails and solar power systems for spacecrafts, he turned to the ladybug for design inspiration.

Notice how, in discussing them, it’s as if we are forced to use the language of design. Regarding ladybugs and their “engineering secrets,” as the NY Times candidly puts it, molecular biologist Douglas Axe tweets:“Like a DeLorean, only cooler!” Here is a DeLorean:In his book Undeniable: How Biology Confirms Our Intuition That Life Is Designed, Dr. Axe uses the illustration of an origami crane. With good reason behind this universal intuition, our minds rebel at the idea that any origami creation could arise through a combination of chance and law, without purpose or design. Yet Darwinian theory demands that we believe a real crane arose that way, or a real ladybug.

The fall of Rome.:The reboot

How to Protect Medical Conscience

Wesley J. Smith

Wesley J. Smith

Over at First Things, I have a piece up about the ongoing and accelerating campaign — most recently furthered by Ezekiel Emanuel — to drive pro-life and orthodox religious believers out of medicine by forcing their participation or complicity in acts in the medical sphere with which they have strong moral or religious objections.

There are currently some conscience protections in the law, but as the piece notes, they are under assault here and are already collapsing in other countries. From“Pro-Lifers Get Out of Medicine”:

The government of Ontario, Canada is on the verge of requiring doctors either to euthanize or to refer all legally qualified patients. In Victoria, Australia, all physicians must either perform an abortion when asked or find an abortionist for the patient.

One doctor has been disciplined under the law for refusing to refer for a sex-selective abortion. In Washington, a small pharmacy chain owned by a Christian family failed in its attempt to be excused from a regulation requiring all legal prescriptions to be dispensed, with a specific provision precluding conscience exemptions. The chain now faces a requirement to fill prescriptions for the morning-after pill, against the owners’ religious beliefs.

In Vermont, a regulation obligates all doctors to discuss assisted suicide with their terminally ill patients as an end-of-life option, even if they are morally opposed. Litigation to stay this forced speech has, so far, been unavailing.

The ACLU recently commenced a campaign of litigation against Catholic hospitals that adhere to the Church’s moral teaching.

Here, I would like to share some ideas about how to shore up existing protections to best protect medical professionals from being forced into committing what they consider sinful or immoral acts. I suggest that the following general principles apply in crafting such protections:

Conscience protections should be legally binding.

The rights of conscience should apply to medical facilities such as hospitals and nursing homes as well as to individuals.

Except in the very rare and compelling circumstance in which a patient’s life is at stake, no medical professional should be compelled to perform or participate in procedures or treatments that take human life.

The rights of conscience should apply most strongly in elective procedures, that is, medical treatments not required to extend the life of, or prevent serious harm to, the patient.

It should be the procedure that is objectionable, not the patient. In this way, for example, physicians could not refuse to treat a lung-cancer patient because the patient smoked or to maintain the life of a patient in a vegetative state because the physician believed that people with profound impairments do not have a life worth living.

No medical professional should ever be forced to participate in a medical procedure intended primarily to facilitate the patient’s lifestyle preferences or desires (in contrast to maintaining life or treating a disease or injury).

To avoid conflicts and respect patient autonomy, patients should be advised, whenever feasible, in advance of a professional’s or facility’s conscientious objection to performing or participating in legal medical procedures or treatments.

The rights of conscience should be limited to bona fide medical facilities such as hospitals, skilled nursing centers, and hospices and to licensed medical professionals such as physicians, nurses, and pharmacists.

I am interested in other ideas on this subject, which I predict will become a firestorm issue in coming years.

Saturday, 20 May 2017

On our latter day frankensteins and the end of science.

Swarm" Science: Why the Myth of Artificial Intelligence Threatens Scientific Discovery

Erik J. Larson

In the last year, two major well-funded efforts have launched in Europe and in the U.S. aimed at understanding the human brain using powerful and novel computational methods: advanced supercomputing platforms, analyzing peta- and even exabyte datasets, using machine learning methods like convolutional neural networks (CNNs), or "Deep Learning."

At the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Lausanne (EPFL), for instance, the Human Brain Project is now underway, a ten-year effort funded by the European Commission to construct a complete computer simulation of the human brain. In the U.S., the Obama Administration has provided an initial $100 million in funding for the newly launched Brain Research Through Advanced Neurotechnologies (BRAIN) Initiative, with funding projected to reach $3 billion in the next ten years. Both projects are billed as major leaps forward in our quest to gain a deeper understanding of the brain -- one of the last frontiers of scientific discovery.

Predictably, given today's intellectual climate, both projects are premised on major confusions and fictions about the role of science and the powers of technology.

The myth of evolving Artificial Intelligence, for one, lies at the center of these confusions. While the U.S. BRAIN Initiative is committed more to the development of measurement technologies aimed at mapping the so-called human connectome -- the wiring diagram of the brain viewed as an intricate network of neurons and neuron circuits -- the Human Brain Project more explicitly seeks to engineer an actual, working simulation of a human brain.

The AI myth drives the HBP vision explicitly, then, even as ideas about Artificial Intelligence and the powers of data-driven methods (aka "Big Data") undergird both projects. The issues raised today in neuroscience are large, significant, and profoundly troubling for science. In what follows, I'll discuss Artificial Intelligence and its role in science today, focusing on how it plays out so unfortunately in neuroscience, and in particular in the high-visibility Human Brain Project in Switzerland.

AI and Science

AI is the idea that computers are becoming intelligent in the same sense as humans, and eventually to even a greater degree. The idea is typically cast by AI enthusiasts and technologists as forward-thinking and visionary, but in fact it has profoundly negative affects on certain very central and important features of our culture and intellectual climate. Its eventual effects are to distract us from using our own minds.

The connection here is obvious, once you see it. If we believe that the burden of human thinking (and here I mean, particularly, explaining the world around us) will be lessened because machines are rapidly gaining intelligence, the consequence to science if this view is fictitious can only be to diminish and ultimately to imperil it.

At the very least, we should expect scientific discovery not to accelerate, but to remain in a confused and stagnant state with this set of ideas. These ideas dominate today.

Look at the history of science. Scientists have grand visions and believe they can explain the world by contact of the rational mind with nature. One thinks of Einstein, but many others as well: Copernicus, Galileo, Newton, Maxwell, Hamilton, Heisenberg, even Watson and Crick.

Copernicus, for instance, became convinced that the entire Ptolemaic model of the solar system stemmed from false theory. His heliocentric model is a case study in the triumph of the human mind not to analyze data but effectively to ignore it -- seeking a more fundamental explanation of observation in a rational vision that is not data-driven but prior to and more fundamental than what we collect and view (the "data"). Were computers around back then, one feels that Copernicus would have ignored their results too, so long as they were directed at analyzing geocentric models. Scientific insight here is key, yesterday and today.

Yet the current worldview is committed, incessantly and obsessively, to reducing scientific insight to "swarms" of scientists working on problems, by each making little contributions to a framework that is already in place. The Human Brain Project here is paradigmatic: the "swarm" language is directly from a key HBP contributor Sean Hill (in the recent compilation The Future of the Brain edited by Gary Marcus, whom I like).

The swarm metaphor evokes thoughts of insects buzzing around, fulfilling pre-ordained roles. So if we're convinced that in a Human-Technology System the "technology" is actually becoming humanly intelligent (the AI myth), the set of social and cultural beliefs begin to change to accommodate a technology-centered worldview. This, however, provides very little impetus for discovery.

To the extent that individual minds aren't central to the technology-driven model of science, then "progress" based on "swarm science" further reinforces the belief that computers are increasingly responsible for advances. It's a self-fulfilling vision; the only problem is that fundamental insights, not being the focus anyway, are also the casualties of this view. If we're living in a geocentric universe with respect to, say, neuroscience still, the model of "swarm" science and data-driven analysis from AI algorithms isn't going to correct us. That's up to us: in the history of science, today, and in our future.

An example. Neuroscientists are collecting massive datasets from neural imaging technologies (not itself a bad thing), believing that machine-learning algorithms will find interesting patterns in the data. When the problem is well defined, this makes sense.

But reading the literature, it's clear that the more starry-eyed among the neuroscientists (like Human Brain Project director Henry Markram) also think that such an approach will obviate the need for individual theory in favor of a model where explanation "emerges" from a deluge of data.

This is not a good idea. For one thing, science doesn't work that way. The "swarm-and-emerge" model of science would seem ridiculous were it not for the belief that such massive quantities of data run on such powerful computing resources ("massive" and "powerful" is part of the emotional component of this worldview) could somehow replace traditional means of discovery, where scientists propose hypotheses and design specific experiments to generate particular datasets to test those hypotheses.

Now, computation is supposed to replace all that human-centered scientific exploration -- Markram himself has said publicly that the thousands of individual experiments are too much for humans to understand. It may be true that the volume of research is daunting, but the antidote can hardly be to force thousands of labs to input data into a set of APIs that presuppose a certain, particular theory of the brain! (This is essentially what the Human Brain Project does.) We don't have the necessary insights, yet, in the first place.

Even more pernicious, the belief that technology is "evolving" and getting closer and closer to human intelligence gives less and less an impetus to people to fight for traditional scientific practice, centered on discovery. If human thought is not the focus anymore, why empower all those individual thinkers? Let them "swarm," instead, around a problem that has been pre-defined.

This too is an example of how the AI myth also encourages a kind of non-egalitarian view of things, where a few people are actually telling everyone else what to do, even as the model is supposed to be communitarian in spirit. This gets us a little too far off topic presently, but is a fascinating case study in how false narratives are self-serving in subtle ways.

Back to science. In fact the single best worldview for scientific discovery is simple: human minds explain data with theory. Now, but only after we have this belief, we can and should insert: and our technology can help us. Computation is a tool -- a very powerful one, but as it isn't becoming intelligent in the sense of providing theory for us, we can't then jettison our model of science, and begin downplaying or disregarding the theoretical insights that scientists (with minds) provide.

This is a terrible idea. It's just terrible. It's no wonder that any major scientific successes in the last decade have been largely engineering-based, like the Human Genome Project. No one has the patience, or even the faith, to fund smaller-scale and more discovery-based efforts.

The idea, once again, is that the computational resources will somehow replace traditional scientific practice, or "revolutionize it" -- but as I've been at pains to argue, computation isn't "smart" in the way people are, and so the entire AI Myth is not positive, or even neutral, but positively threatening to real progress.

The End of Theory? Maybe So

Hence when Chris Andersen wrote in 2007 that Big Data and super computing (and machine learning or i.e., induction) meant the "End of Theory," he echoed the popular Silicon Valley worldview that machines are evolving a human -- and eventually a superhuman -- intelligence, and he simultaneously imperiled scientific discovery. Why? Because (a) machines aren't gaining abductive inference powers, and so aren't getting smart in the relevant manner to underwrite "end of theory" arguments, and (b) ignoring the necessity of scientists to use their minds to understand and explain "data" is essentially gutting the central driving force of scientific change.

To put this yet again on more practical footing, over five hundred neuroscientists petitioned the EU last year because a huge portion of funding for fundamental neuroscience research (over a billion euro) went to the Human Brain Project, which is an engineering effort that presupposes that fundamental pieces of theory about the brain are in place. The only way a reasonable person could believe that, is if he were convinced that the Big Data/AI model would yield those theoretical fruits somehow along the way. When pressed, however, the silence as to how exactly that will happen is deafening.

The answer Markram and others want to provide -- if only sci-fi arguments worked on EU officials or practicing neuroscientists -- is that the computers will keep getting "smarter." And so that myth is really at the root of a lot of current confusion. Make no mistake, the dream of AI is one thing, but the belief that AI is around the corner and inevitable is just a fiction, and potentially a harmful one at that.

To chance and necessity be the glory?

Moths Defy the Possible

Evolution News & Views

How do you make choices in a data-poor environment? Imagine being in a dark room in total silence. Every few seconds, a tiny flash of light appears. You might keep your eyes open as long as possible to avoid missing any of them. You might watch the flashes over time to see if there's a pattern. If you see a pattern, you might deduce it will lead to further information.

The ability to navigate this way in a dim world is called a summation strategy. "This slowing visual response is consistent with temporal summation, a visual strategy whereby the visual integration time (or 'shutter time') is lengthened to increase visual reliability in dim light," Eric Warrant explains in Science. He's discussing how hawkmoths perform "Visual tracking in the dead of night," and he's clearly impressed by how amazingly well insects "defy the possible" as they move through the world:

Nocturnal insects live in a dim world. They have brains smaller than a grain of rice, and eyes that are even smaller. Yet, they have remarkable visual abilities, many of which seem to defy what is physically possible. On page 1245 of this issue, Sponberget al. reveal how one species, the hawkmoth Manduca sexta, isable to accurately track wind-tossed flowers in near darknessand remain stationary while hovering and feeding. [Emphasis added.]

The hawkmoth has some peers on the Olympic award platform:

Examples of remarkable visual abilities include the nocturnal central American sweat bee Megalopta genalis, which can use learned visual landmarks to navigate from its nest -- aninconspicuous hollowed-out twig hanging in the tangled undergrowth -- through a dark and complex rainforest to a distant source of nocturnal flowers, and then return. The nocturnalAustralian bull ant Myrmecia pyriformis manages similar navigational feats on foot. Nocturnal South African dung beetles can use the dim celestial pattern of polarized light around the moon or the bright band of light in the Milky Way as a visual compass to trace out a beeline when rolling dung balls. Some nocturnal insects, like the elephant hawkmoth Deilephila elpenor, even have trichromatic color vision.

These insects pack a lot of computing power in brains the size of a grain of rice. How do they do it? Part of the answer lies in the fine-tuning between object and sensor:

It turns out that even though the hawkmoths must compromise tracking accuracy to meet the demands of visual motiondetection in dim light, the tracking error remains small exactly over the range of frequencies with which wind-tossed flowers move in the wild. The results reveal a remarkable match between the sensorimotor performance of an animal and the dynamics of the sensory stimulus that it most needs to detect.

A tiny brain imposes real-world constraints on processing speed. The hawkmoth, so equipped, faces limits on sensorimotor performance: how sensitive its eyes are in dim light, how quickly it can perceive motion in the flower, and how fast it can move its muscles to stay in sync. The moth inserts its proboscis into the flower, and if a breeze moves the flower about, the moth has to be able to keep up with it to get its food. To meet the challenge, its brain software includes the "remarkable" ability to perform data summation and path integration fast enough to move with the flower while it feeds.

In their experiments, Sponberg et al. observed hawkmoths in a specially designed chamber. They were able to control light levels and move artificial flowers containing a sugar solution at different speeds. "During experiments, this flower was attached to a motorized arm that moved the flower from side to side in a complex trajectory," Warrant says.

The component movement frequencies of this trajectory varied over two orders of magnitude and encompassed the narrower range of frequencies typical of wind-tossed flowers. A hovering moth fed from the flower by extending its proboscis into the reservoir, rapidly flying from side to side to maintain feeding bystabilizing the moving flower in the center of its visual field.

The experiment allowed the researchers to cross the line from possible to impossible, showing at what point the moth could not keep up. Dimmer light requires longer integration time, while faster motion requires quicker muscle response. Still, these little flyers "tracked the flower remarkably well" by using the temporal summation strategy.

Hummingbirds feed on moving flowers, too, but usually in broad daylight. To find this ability to track a moving food source in a tinier creature possessing a much smaller brain is truly amazing -- especially considering that it has less light to see by.

This strategy has recently been demonstrated in bumblebeesflying in dim light and has been predicted for nocturnalhawkmoths. Although temporal summation sacrifices the perception of faster objects, it strengthens the perception of slower ones, like the slower movement frequencies (below ~2 Hz) of the robotic flower.

... and that just happens to be the maximum speed of the natural flowers in the moth's environment. How did this perfect match arise? Why, natural selection, of course. Here comes the narrative gloss:

By carefully analyzing the movements of several species of flowers tossed by natural winds -- including those favored by hawkmoths -- Sponberg et al. discovered that their movements were confined to frequencies below ~2 Hz. Thus, despite visual limitations in dim light, the flight dynamics and visual summation strategies of hovering hawkmoths have evolved to perfectly match the movement characteristics of flowers, their only food source.The implications of the study go far beyond this particular species. It shows how in small animals like hawkmoths, withlimited nervous system capacities and stretched energy budgets, the forces of natural selection have matched sensory and motorprocessing to the most pressing ecological tasks that animals must perform in order to survive. This is done not by maximizing performance in every possible aspect of behavior, but bystripping away everything but the absolutely necessary andhoning what remains to perform tasks as accurately and efficiently as possible.

Do the experimenters agree with this narrative? They actually have little to say about evolution. Near the end of the paper, they speculate a little:

The frequencies with which a moth can maneuver could provide a selective pressure on the biomechanics of flowers to avoidproducing floral movements faster than those that the moth can track in low light. The converse interaction -- flower motions selecting on the moth -- could also be important, suggesting acoevolutionary relationship between pollinator and plant thatextends beyond color, odor, and spatial features to include motion dynamics.

The evolutionary narrative, though, is unsatisfying. It is only conceptual, not empirical (nobody saw the flower and moth co-evolve). Additionally, flowers could just as well thrive with other pollinators that operate during the daytime. Or, the moth could simply adjust its biological clock to feed in better light, too. The theory, "It is, therefore it evolved" could explain anything.

Warrant also mischaracterizes natural selection as a force. Natural selection is more like a bumper than a force; it's the hub in the pinball game, not the flipper that an intelligent agent uses. It's far easier for a moth to drop the ball in the hole (i.e., go extinct) than to decide what capacities it must stretch to match the hubs in its game. The hub, certainly, cares nothing about whether the player wins or not. It's not going to tell the moth, "Pssst ... strip away everything that's not absolutely necessary, and hone what remains, and you might win!" Personifying natural selection in this way does not foster scientific understanding.

Worst of all, the evolutionary explanation presupposes the existence of highly complex traits that are available to be stripped or honed: flight, a brain, muscles -- the works. You can't hone what isn't there.

What we observe is a tightly adapted relationship between flower and moth that reaches to the limits of the possible. Any stripping or honing comes not from the environment, but from internal information encoded in the organism. Intelligent causes know how to code for robustness, so that a program can work in a variety of circumstances. Seeing this kind of software packed into a computer the size of a grain of rice makes the design inference even more compelling.

Illustra Media's documentary Metamorphosis showed in vibrant color the remarkable continent-spanning migration of the Monarch butterfly. Their new documentary, Living Waters (coming out this summer), shows dramatic examples of long-distance migration and targeting in the oceans and rivers of the earth, where the lack of visual cues makes finding the target even more demanding. The film makes powerful arguments against the abilities of natural selection, and for the explanatory fruitfulness of intelligent design

Why so little evolving across the history of life?

A Good Question from Michael Denton About the Fixity of Animal Body Plans

David Klinghoffer September 9, 2011 6:00 AM

Biochemist Michael Denton (Evolution: A Theory in Crisis, Nature's Destiny: How the Laws of Biology Reveal Purpose in the Universe) was in our offices this week and he casually posed a question that I, for one, had never considered. Hundreds of millions of years ago, all these animal body plans became fixed. They stayed as they were and still are so today.

Before that -- I'm putting this my way, so if I get anything wrong blame me -- of course they had been, under Darwinian assumptions, morphing step-by-step, with painful gradualness. Then they just stopped and froze in their tracks.

The class Insecta with its distinctive segmentation, for example, goes back more than 400 million years to the Silurian period. It gives the impression of a creative personality at work in a lab. He hits on a design he likes and sticks with it. It does not keep morphing.

This is exactly the way I am about recipes. I experiment with dinner plans, discover something I like, and then repeat it endlessly with minor variations from there onward.

Why does the designer or the cook like it that way? Well, he just does. There's no reason that can be expressed in traditional Darwinian adaptive terms. There is no adaptive advantage in this fixity of body plans. Why not keep experimenting and morphing as an unguided, purposeless process would be expected to do? But nature doesn't work that way. It finds a good plan and holds on to it fast, for dear life. This suggests purpose, intelligence, thought, design. Or is there something I'm missing?

David Klinghoffer September 9, 2011 6:00 AM

Biochemist Michael Denton (Evolution: A Theory in Crisis, Nature's Destiny: How the Laws of Biology Reveal Purpose in the Universe) was in our offices this week and he casually posed a question that I, for one, had never considered. Hundreds of millions of years ago, all these animal body plans became fixed. They stayed as they were and still are so today.

Before that -- I'm putting this my way, so if I get anything wrong blame me -- of course they had been, under Darwinian assumptions, morphing step-by-step, with painful gradualness. Then they just stopped and froze in their tracks.

The class Insecta with its distinctive segmentation, for example, goes back more than 400 million years to the Silurian period. It gives the impression of a creative personality at work in a lab. He hits on a design he likes and sticks with it. It does not keep morphing.

This is exactly the way I am about recipes. I experiment with dinner plans, discover something I like, and then repeat it endlessly with minor variations from there onward.

Why does the designer or the cook like it that way? Well, he just does. There's no reason that can be expressed in traditional Darwinian adaptive terms. There is no adaptive advantage in this fixity of body plans. Why not keep experimenting and morphing as an unguided, purposeless process would be expected to do? But nature doesn't work that way. It finds a good plan and holds on to it fast, for dear life. This suggests purpose, intelligence, thought, design. Or is there something I'm missing?

Friday, 19 May 2017

No such thing as bad publicity?

How Curiosity Overcomes the Yuck Factor: A Positive Take on Negative Reviews

Douglas Axe | @DougAxe

I’ve been arguing that intelligent design explains life better than Darwin’s theory for long enough to be familiar with reactions that amount to little more than disgust — the yuck response. Usually I take that response as a sign that I need to move on to more receptive listeners, but I was recently reminded that the yuck response doesn’t always end the discussion. A colleague of mine — a former Darwinist who now sees life as designed — told me how he came to change his view several years ago. It was curiosity that bumped him out of the Darwinian rut, by compelling him to give a few of the best books on intelligent design a serious read.Kriti Sharma’s yuck reaction to my book, Undeniable: How Biology Confirms our Intuition That Life Is Designed, in her recent review suggests she might be stuck in that same rut. She read the book, but not very seriously.

Sharma, a PhD biology student at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, describes giving lectures to other students on the evolutionary divergence between clams and snails. According to the evolutionary story, something quite different from modern clams or snails had descendants that became modern clams and snails in all their great variety. Anyone with an appreciation of all the distinct biological marvels represented by that variety should be struck by the magnitude of this claim. Add just a dash of curiosity to that awe, and you start to wonder how a blind evolutionary process could actually pull it off. How can something utterly devoid of insight possibly appear so insightful?

Sharma’s vagueness on this point is the familiar sign that curiosity hasn’t yet kicked in. She says evolution gets lots of trials with lots of feedback, each small step depending on the prior step. She seems satisfied with that. The staggering variety of stunning living things that populate our planet is adequately explained by those rather unimpressive factors — time and natural selection — she thinks. In her case, my attempts to expose the inadequacy of those factors seem to have fallen on deaf ears.

Much of my book is devoted to developing an argument around everyday experience and common sense, a combination I refer to as common science. It seems to me that Darwin’s thinking is quite vulnerable to refutation by common science. After all, selection doesn’t really make anything. It merely chooses among things that have already been made. That’s what the word means. The only kind of selection that gives you clams or snails is the kind you do while ordering dinner at a French restaurant.

Sharma dismisses such thoughts as childish “pre-theoretical” thinking.

One of my book’s themes is that we adults shy away from common-science deductions like that for the wrong reasons. Fearing that smart people couldn’t possibly have overlooked such obvious facts for so long, we tend to assume they must know something the rest of us don’t. But in making that assumption, we overlook something equally obvious, which is that smart people take great pride in their smarts. Wanting to be revered for their intellects, they’re very reluctant to say anything that might cause their status to take a hit. Ironically, the end result of all this fretting about appearances is that the “smart” explanation of biological origins has the same amount of substance to it as the emperor’s new clothes — worn with just as much pride.

Another theme of my book is that because common science gives us the right conclusion about our origin, deeper digging consistently affirms that conclusion. No matter how deeply we dig, if we keep curiosity at the forefront we find our intuitive rejection of the inventive power of natural selection to be absolutely correct.

Half-a-minute’s worth of digging might convince you of this.

Consider, for example, Graham Bell, the James McGill Professor of Biology at McGill University and a recently elected Fellow of the Royal Society. He’s an accomplished evolutionary biologist, author of a book titled Selection: The Mechanism of Evolution, where he argues that “Living complexity cannot be explained except through selection, and does not require any other category of explanation whatsoever.” According to Bell, then, selection most certainly is evolution’s engine of invention.

Now consider Andreas Wagner of the Department of Evolutionary Biology and Environmental Studies at the University of Zurich, who is also an accomplished evolutionary biologist. His book, Arrival of the Fittest: Solving Evolution’s Greatest Puzzle, confirms common science by declaring that “natural selection is not a creative force. It does not innovate, but merely selects what is already there.”

Notice that Wagner’s assessment, contrary to Bell’s, leaves a rather large and conspicuous hole right in the middle of evolutionary theory. “To appreciate the magnitude of the problem,” says Wagner, “consider that every one of the differences between humans and the first life forms on earth was once an innovation: an adaptive solution to some unique challenge faced by a living being.” According to Wagner, then, selection most certainly is not evolution’s engine of invention.

Don’t miss the significance of this. Two highly regarded experts at the very center of today’s evolutionary thinking have completely opposite opinions about how evolution is supposed to work! What this really means, of course, is that the community of evolutionary biologists has no clue how evolution would work! Again, add just a pinch of curiosity to that startling realization and you start to wonder whether evolution really can work.

That’s what drove me to test Darwin’s idea in the lab for the last twenty years. As I explain in Undeniable, his theory has failed this testing consistently and spectacularly.

Now, I’m very willing to hear from anyone who thinks otherwise, as long as they show genuine curiosity of the kind that rises above academic peer pressure by refusing to settle for stock explanations that are obviously inadequate. Kriti Sharma seems content to leave her worldview undisturbed for the moment, which is understandable.

That was my colleague before curiosity got the better of him.

Douglas Axe | @DougAxe

I’ve been arguing that intelligent design explains life better than Darwin’s theory for long enough to be familiar with reactions that amount to little more than disgust — the yuck response. Usually I take that response as a sign that I need to move on to more receptive listeners, but I was recently reminded that the yuck response doesn’t always end the discussion. A colleague of mine — a former Darwinist who now sees life as designed — told me how he came to change his view several years ago. It was curiosity that bumped him out of the Darwinian rut, by compelling him to give a few of the best books on intelligent design a serious read.Kriti Sharma’s yuck reaction to my book, Undeniable: How Biology Confirms our Intuition That Life Is Designed, in her recent review suggests she might be stuck in that same rut. She read the book, but not very seriously.

Sharma, a PhD biology student at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, describes giving lectures to other students on the evolutionary divergence between clams and snails. According to the evolutionary story, something quite different from modern clams or snails had descendants that became modern clams and snails in all their great variety. Anyone with an appreciation of all the distinct biological marvels represented by that variety should be struck by the magnitude of this claim. Add just a dash of curiosity to that awe, and you start to wonder how a blind evolutionary process could actually pull it off. How can something utterly devoid of insight possibly appear so insightful?

Sharma’s vagueness on this point is the familiar sign that curiosity hasn’t yet kicked in. She says evolution gets lots of trials with lots of feedback, each small step depending on the prior step. She seems satisfied with that. The staggering variety of stunning living things that populate our planet is adequately explained by those rather unimpressive factors — time and natural selection — she thinks. In her case, my attempts to expose the inadequacy of those factors seem to have fallen on deaf ears.

Much of my book is devoted to developing an argument around everyday experience and common sense, a combination I refer to as common science. It seems to me that Darwin’s thinking is quite vulnerable to refutation by common science. After all, selection doesn’t really make anything. It merely chooses among things that have already been made. That’s what the word means. The only kind of selection that gives you clams or snails is the kind you do while ordering dinner at a French restaurant.

Sharma dismisses such thoughts as childish “pre-theoretical” thinking.

One of my book’s themes is that we adults shy away from common-science deductions like that for the wrong reasons. Fearing that smart people couldn’t possibly have overlooked such obvious facts for so long, we tend to assume they must know something the rest of us don’t. But in making that assumption, we overlook something equally obvious, which is that smart people take great pride in their smarts. Wanting to be revered for their intellects, they’re very reluctant to say anything that might cause their status to take a hit. Ironically, the end result of all this fretting about appearances is that the “smart” explanation of biological origins has the same amount of substance to it as the emperor’s new clothes — worn with just as much pride.

Another theme of my book is that because common science gives us the right conclusion about our origin, deeper digging consistently affirms that conclusion. No matter how deeply we dig, if we keep curiosity at the forefront we find our intuitive rejection of the inventive power of natural selection to be absolutely correct.

Half-a-minute’s worth of digging might convince you of this.

Consider, for example, Graham Bell, the James McGill Professor of Biology at McGill University and a recently elected Fellow of the Royal Society. He’s an accomplished evolutionary biologist, author of a book titled Selection: The Mechanism of Evolution, where he argues that “Living complexity cannot be explained except through selection, and does not require any other category of explanation whatsoever.” According to Bell, then, selection most certainly is evolution’s engine of invention.

Now consider Andreas Wagner of the Department of Evolutionary Biology and Environmental Studies at the University of Zurich, who is also an accomplished evolutionary biologist. His book, Arrival of the Fittest: Solving Evolution’s Greatest Puzzle, confirms common science by declaring that “natural selection is not a creative force. It does not innovate, but merely selects what is already there.”

Notice that Wagner’s assessment, contrary to Bell’s, leaves a rather large and conspicuous hole right in the middle of evolutionary theory. “To appreciate the magnitude of the problem,” says Wagner, “consider that every one of the differences between humans and the first life forms on earth was once an innovation: an adaptive solution to some unique challenge faced by a living being.” According to Wagner, then, selection most certainly is not evolution’s engine of invention.

Don’t miss the significance of this. Two highly regarded experts at the very center of today’s evolutionary thinking have completely opposite opinions about how evolution is supposed to work! What this really means, of course, is that the community of evolutionary biologists has no clue how evolution would work! Again, add just a pinch of curiosity to that startling realization and you start to wonder whether evolution really can work.

That’s what drove me to test Darwin’s idea in the lab for the last twenty years. As I explain in Undeniable, his theory has failed this testing consistently and spectacularly.

Now, I’m very willing to hear from anyone who thinks otherwise, as long as they show genuine curiosity of the kind that rises above academic peer pressure by refusing to settle for stock explanations that are obviously inadequate. Kriti Sharma seems content to leave her worldview undisturbed for the moment, which is understandable.

That was my colleague before curiosity got the better of him.

Why enzymes are undeniably designed.

Don’t Be Intimidated by Keith Fox on Intelligent Design

Douglas Axe | @DougAxe

Darwin believed that once simple bacteria appeared on Earth (however that happened), natural selection took over from there — creating every living thing from that humble beginning. And this continues to be the official view of the science establishment to this day.

Being skeptical of that view, my colleagues and I have spent twenty-some years putting Darwin’s idea to one test after another in the lab. As described in a stack of peer-reviewed technical papers, it has failed every one of these tests. I’m convinced, however, that you don’t need a PhD to see why it had to fail. That’s why I based my recent book — Undeniable: Undeniable: How Biology Confirms Our Intuition That Life Is Designed — on commonsense reasoning instead of technical argument.

Biochemist Keith Fox at the University of Southampton didn’t like the book, so he wrote a short critique claiming I got it all wrong. The things I’ve studied for all these years are called enzymes — sophisticated catalysts that handle all the chemical processes inside cells. Based on my work and the work of many others, I claim that these remarkable little factories can’t have come about by any ordinary physical process. I say they’re molecular masterpieces — works of genius. Fox disagrees, and while he doesn’t seem to have done any work in the field, his critique of Undeniable includes his own rough-and-ready theory of enzyme origins.

As I recently recounted, Fox thinks working enzymes started out much smaller than they are today, growing to their present size through the refining work of natural selection. Years ago, I explained in technical detail why this can’t be true — why enzymes must be full-sized and exquisitely shaped to do their jobs. But, again, a major theme of my book is that you don’t have to take my word for this. You can see for yourself that life is designed all the way down to the molecular level.

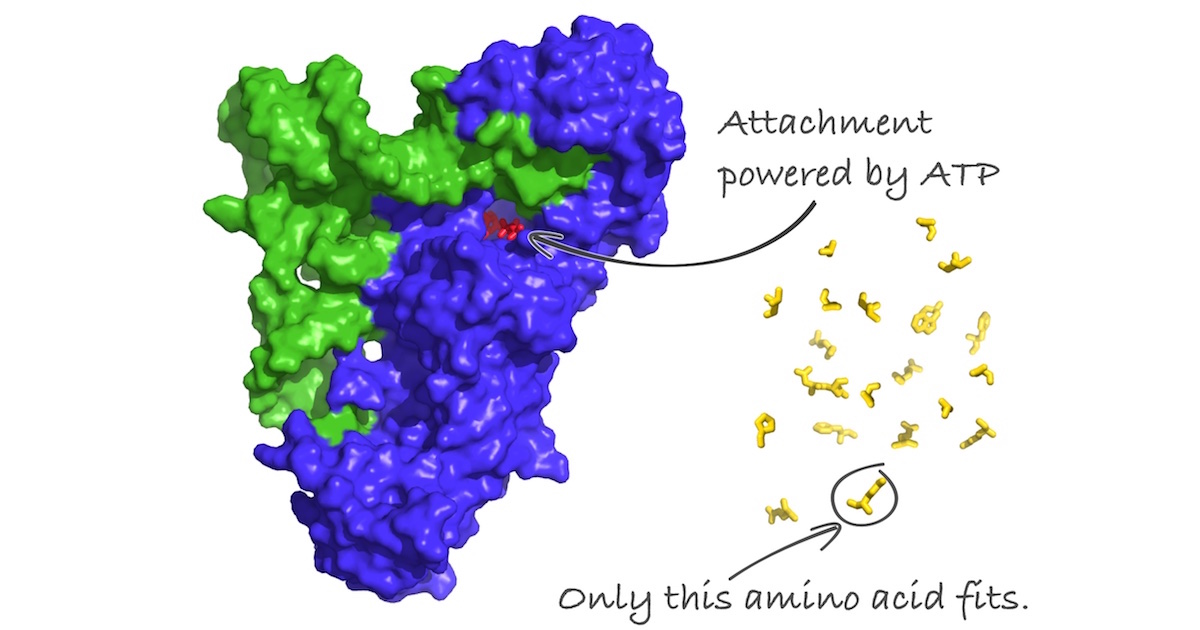

Here’s one visual example to make the point.

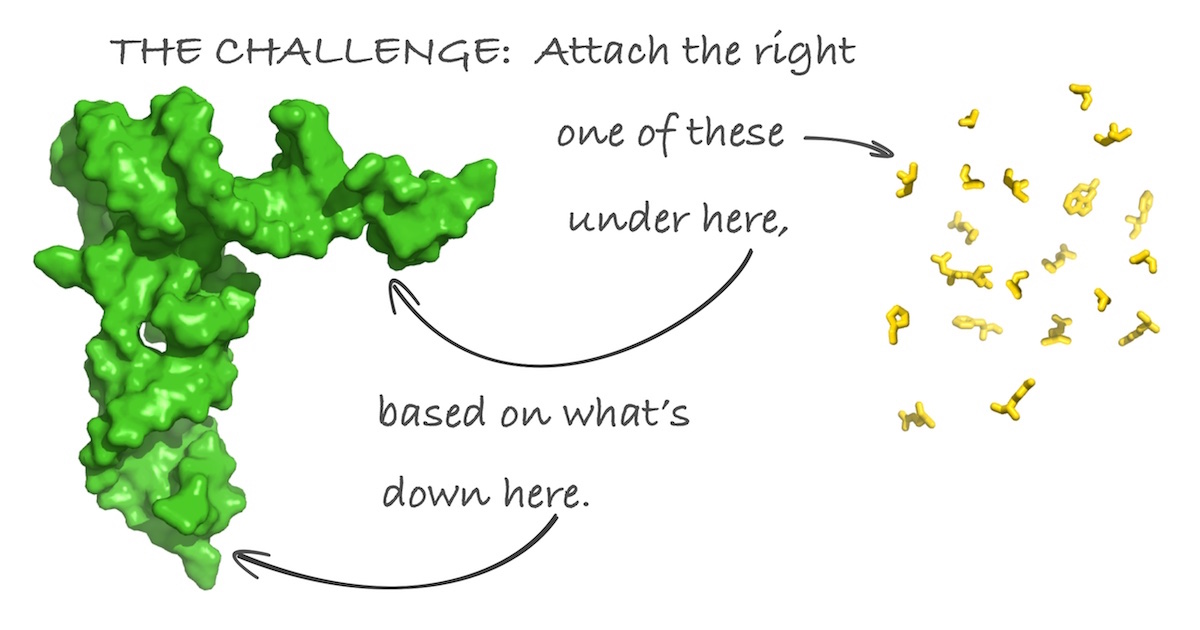

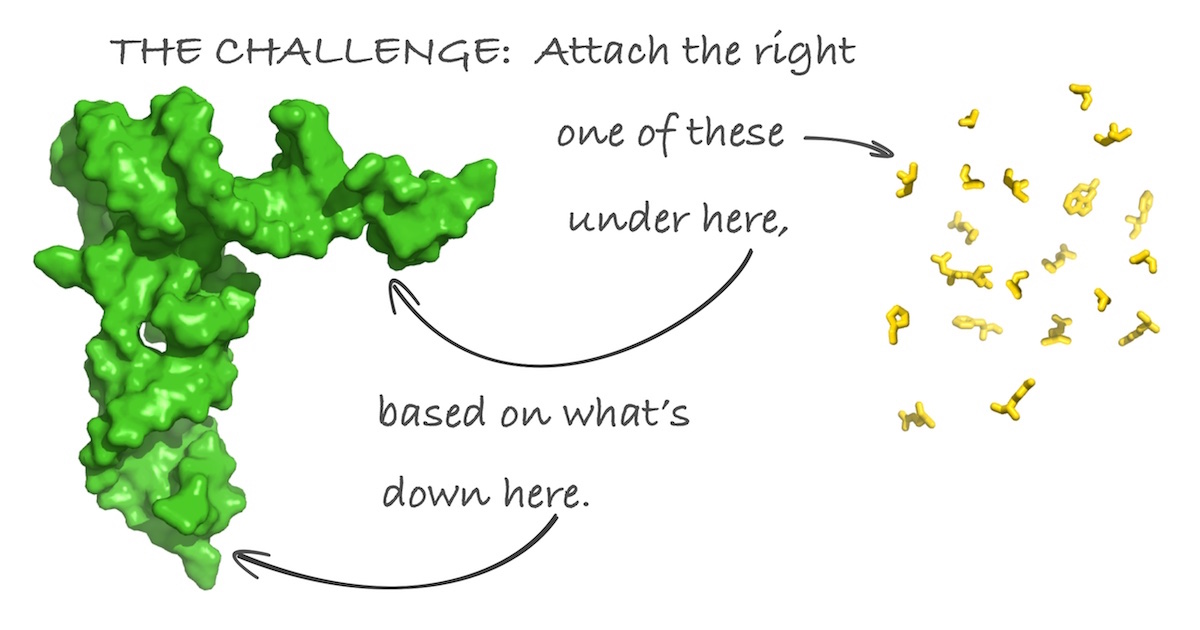

That green thing is a large molecule called tRNA, and the little yellow things are amino acids. For life to work, these amino acids, which come in 20 different kinds, must be connected in special sequences to make chain-like molecules called proteins (enzymes being one class of proteins). If these long molecules were nothing but floppy chains, they would be useless. Instead, their special sequences cause them to fold up into distinct and highly useful shapes, each as well suited to its specific function as any human-made machine.

The crucial instructions for the sequences that cause these machine-like shapes to form are preserved in the form of genes, used in every living cell and carefully passed to successive generations. A set of tRNA molecules like that green one is crucial for reading these genes to make proteins. The tRNA molecules work like clever adapters: their underside recognizes (by perfect fit) a specific short piece of genetic sequence — a genetic word, if you will — while their top part holds the amino acid that, in the language of genes, is referred to by that word.

In order for this to work, something has to make sure each different green thing gets the right amino acid attached at the top — meaning the one corresponding to the genetic “word” recognized down below. As if that weren’t challenging enough, those little yellow amino acids are attached to the green things only with difficulty. They must be forced into position and then locked in place with a chemical bond.

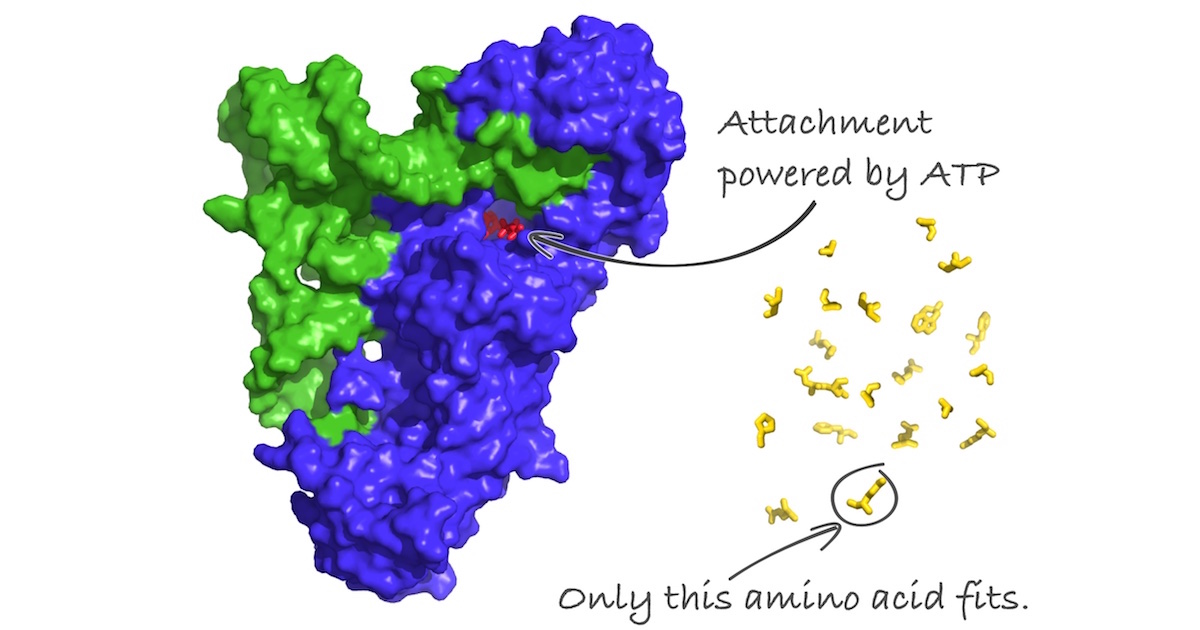

Life’s ingenious solution to these compound challenges is a set of enzymes like the one shown here in blue.

Each of these enzymes recognizes its own type of tRNA molecule, checking the bottom part to make sure it will read the right genetic word and simultaneously recognizing the amino acid corresponding to this genetic word. In power-tool fashion, these enzymes “burn” ATP to forcibly attach the correct amino acid into position on the tRNA (in the above picture you can see the red ATP in place, ready for the correct amino acid to enter the opening and be forced into place).

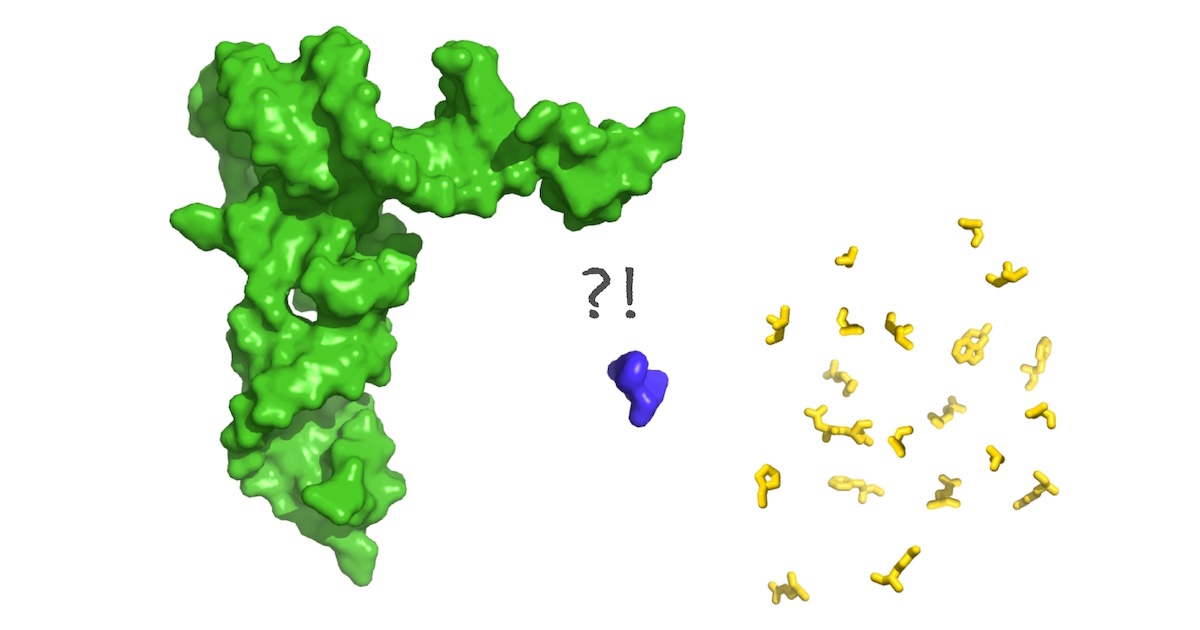

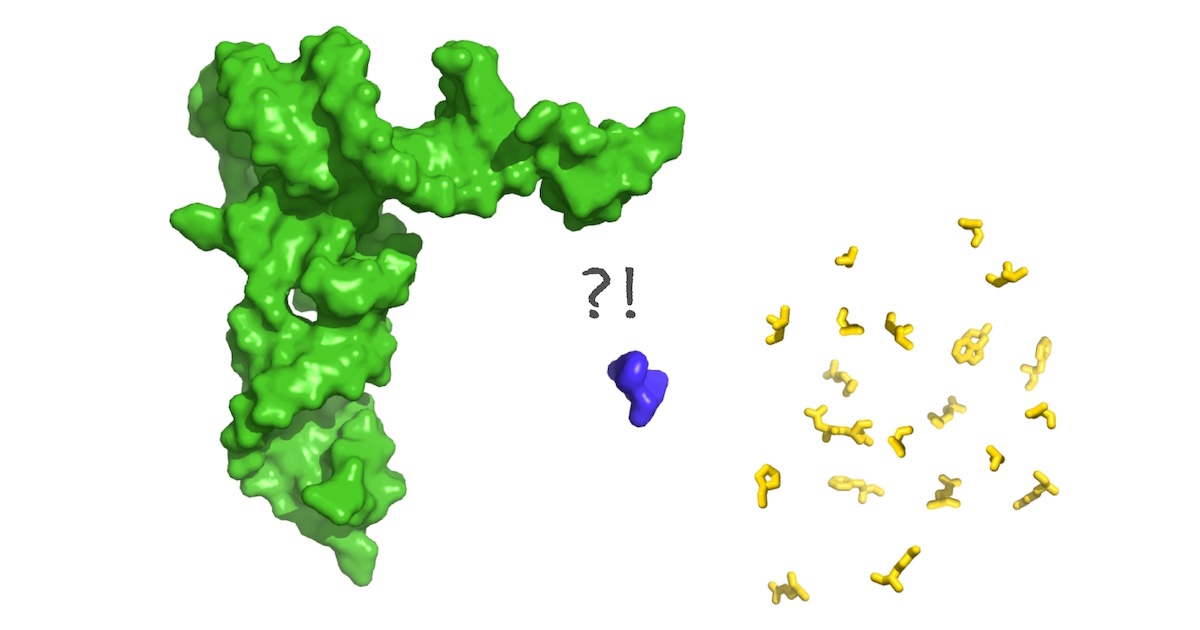

Sophisticated power tools don’t appear out of thin air, though. So, wanting to think otherwise, Keith Fox imagined much simpler things that could come out of thin air, proposing that these can do crudely what today’s enzymes do so elegantly. Specifically, the little blue blob below is what Fox imagined.

Now, imagination can be useful in science, but only by connecting in a compelling way to reality. As anyone can plainly see, that isn’t the case here. In fact, the absence of evidence to back Fox’s claim up, while significant, isn’t nearly as significant as the fact that we can all see why his claim simply can’t work. Little blobs like that (nothing but two amino acids joined together) can’t possibly verify the bottom of the tRNA…much less do so while recognizing the corresponding amino acid…much less hold the needed ATP in position to power the attachment of that amino acid. And while the comical inadequacy of the size of that little blob is what jumps out at us, this isn’t just about size. Rather, it’s about the necessity of matching shape to function.

Other examples could be given by the thousands (literally) — each showing how woefully inadequate Fox’s little blobs are. But you get the point.

The only thing Keith Fox’s theory of enzyme origins has going for it is that it came from Keith Fox — a fully credentialed and highly competent biochemist at a major research university. In other words, his claim borrows any status it has from his professional standing. But when a scientist, however accomplished, stubbornly wants to see things one way, this borrowed status just isn’t enough.

Surprised? On the one hand, you shouldn’t be…but on the other, you’re in good company if you are. Many people are so persuaded by the stereotypical view of scientists that they can’t imagine how these supposedly uber-rational thinkers could allow their desires to interfere with their reasoning.

Rest assured that they can. Scientist are, after all, just as human as everyone else.

Douglas Axe | @DougAxe

Darwin believed that once simple bacteria appeared on Earth (however that happened), natural selection took over from there — creating every living thing from that humble beginning. And this continues to be the official view of the science establishment to this day.

Being skeptical of that view, my colleagues and I have spent twenty-some years putting Darwin’s idea to one test after another in the lab. As described in a stack of peer-reviewed technical papers, it has failed every one of these tests. I’m convinced, however, that you don’t need a PhD to see why it had to fail. That’s why I based my recent book — Undeniable: Undeniable: How Biology Confirms Our Intuition That Life Is Designed — on commonsense reasoning instead of technical argument.

Biochemist Keith Fox at the University of Southampton didn’t like the book, so he wrote a short critique claiming I got it all wrong. The things I’ve studied for all these years are called enzymes — sophisticated catalysts that handle all the chemical processes inside cells. Based on my work and the work of many others, I claim that these remarkable little factories can’t have come about by any ordinary physical process. I say they’re molecular masterpieces — works of genius. Fox disagrees, and while he doesn’t seem to have done any work in the field, his critique of Undeniable includes his own rough-and-ready theory of enzyme origins.

As I recently recounted, Fox thinks working enzymes started out much smaller than they are today, growing to their present size through the refining work of natural selection. Years ago, I explained in technical detail why this can’t be true — why enzymes must be full-sized and exquisitely shaped to do their jobs. But, again, a major theme of my book is that you don’t have to take my word for this. You can see for yourself that life is designed all the way down to the molecular level.

Here’s one visual example to make the point.

That green thing is a large molecule called tRNA, and the little yellow things are amino acids. For life to work, these amino acids, which come in 20 different kinds, must be connected in special sequences to make chain-like molecules called proteins (enzymes being one class of proteins). If these long molecules were nothing but floppy chains, they would be useless. Instead, their special sequences cause them to fold up into distinct and highly useful shapes, each as well suited to its specific function as any human-made machine.

The crucial instructions for the sequences that cause these machine-like shapes to form are preserved in the form of genes, used in every living cell and carefully passed to successive generations. A set of tRNA molecules like that green one is crucial for reading these genes to make proteins. The tRNA molecules work like clever adapters: their underside recognizes (by perfect fit) a specific short piece of genetic sequence — a genetic word, if you will — while their top part holds the amino acid that, in the language of genes, is referred to by that word.

In order for this to work, something has to make sure each different green thing gets the right amino acid attached at the top — meaning the one corresponding to the genetic “word” recognized down below. As if that weren’t challenging enough, those little yellow amino acids are attached to the green things only with difficulty. They must be forced into position and then locked in place with a chemical bond.

Life’s ingenious solution to these compound challenges is a set of enzymes like the one shown here in blue.

Each of these enzymes recognizes its own type of tRNA molecule, checking the bottom part to make sure it will read the right genetic word and simultaneously recognizing the amino acid corresponding to this genetic word. In power-tool fashion, these enzymes “burn” ATP to forcibly attach the correct amino acid into position on the tRNA (in the above picture you can see the red ATP in place, ready for the correct amino acid to enter the opening and be forced into place).

Sophisticated power tools don’t appear out of thin air, though. So, wanting to think otherwise, Keith Fox imagined much simpler things that could come out of thin air, proposing that these can do crudely what today’s enzymes do so elegantly. Specifically, the little blue blob below is what Fox imagined.

Now, imagination can be useful in science, but only by connecting in a compelling way to reality. As anyone can plainly see, that isn’t the case here. In fact, the absence of evidence to back Fox’s claim up, while significant, isn’t nearly as significant as the fact that we can all see why his claim simply can’t work. Little blobs like that (nothing but two amino acids joined together) can’t possibly verify the bottom of the tRNA…much less do so while recognizing the corresponding amino acid…much less hold the needed ATP in position to power the attachment of that amino acid. And while the comical inadequacy of the size of that little blob is what jumps out at us, this isn’t just about size. Rather, it’s about the necessity of matching shape to function.

Other examples could be given by the thousands (literally) — each showing how woefully inadequate Fox’s little blobs are. But you get the point.

The only thing Keith Fox’s theory of enzyme origins has going for it is that it came from Keith Fox — a fully credentialed and highly competent biochemist at a major research university. In other words, his claim borrows any status it has from his professional standing. But when a scientist, however accomplished, stubbornly wants to see things one way, this borrowed status just isn’t enough.

Surprised? On the one hand, you shouldn’t be…but on the other, you’re in good company if you are. Many people are so persuaded by the stereotypical view of scientists that they can’t imagine how these supposedly uber-rational thinkers could allow their desires to interfere with their reasoning.

Rest assured that they can. Scientist are, after all, just as human as everyone else.

Thursday, 18 May 2017

The origins of mankind more mystifying than ever?

Latest Homo naledi Bones Are Younger than Expected

Jonathan Wells

According to a recent article in The Guardian, “New haul of Homo naledi bones sheds surprising light on human evolution,” but the most important word in the headline is “surprising.” It turns out that the fossils are much younger than evolutionary biologists expected.1

In 1982, paleontologists Niles Eldredge and Ian Tattersall noted that it is a “myth that the evolutionary histories of living beings are essentially a matter of discovery.” If this were really true, they wrote, “one could confidently expect that as more hominid fossils were found the story of human evolution would become clearer. Whereas if anything, the opposite has occurred.” The Homo naledi bones show that Eldredge and Tattersall were right.2

Emory University archaeologist Jessica Thompson (quoted in The Guardian) explains that the discovery makes it clear that human evolution is not as straightforward as it is made out to be. “It doesn’t start out with something that looks like a monkey, and then something that looks like an ape, and then something that looks like a human, and then all of a sudden you’ve got people,” she said. “It’s much more complicated than that.”1

Indeed, human origins are as mysterious now as they have ever been. As Yale paleoanthropologist Misia Landau once wrote, stories of human evolution “far exceed what can be inferred from the study of fossils alone,” so fossils are placed “into preexisting narrative structures.”3 And the overarching narrative structure is materialistic philosophy — the view that matter and physical forces are the only realities and God is an illusion.

Science educators tell materialistic stories about how we are accidental by-products of unguided evolution, and the stories are illustrated with iconic drawings of apes morphing into humans. But the stories come first; fossils such as Homo naledi are plugged in later.

References:

(1) Ian Sample, “New haul of Homo naledi bones sheds surprising light on human evolution,” The Guardian (May 9, 2017).

(2) Niles Eldredge and Ian Tattersall, The Myths of Human Evolution (New York: Columbia University Press, 1982), 126–127.

(3) Misia Landau, Narratives of Human Evolution (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1991), pp. ix-x, 148.

Jonathan Wells

According to a recent article in The Guardian, “New haul of Homo naledi bones sheds surprising light on human evolution,” but the most important word in the headline is “surprising.” It turns out that the fossils are much younger than evolutionary biologists expected.1

In 1982, paleontologists Niles Eldredge and Ian Tattersall noted that it is a “myth that the evolutionary histories of living beings are essentially a matter of discovery.” If this were really true, they wrote, “one could confidently expect that as more hominid fossils were found the story of human evolution would become clearer. Whereas if anything, the opposite has occurred.” The Homo naledi bones show that Eldredge and Tattersall were right.2

Emory University archaeologist Jessica Thompson (quoted in The Guardian) explains that the discovery makes it clear that human evolution is not as straightforward as it is made out to be. “It doesn’t start out with something that looks like a monkey, and then something that looks like an ape, and then something that looks like a human, and then all of a sudden you’ve got people,” she said. “It’s much more complicated than that.”1

Indeed, human origins are as mysterious now as they have ever been. As Yale paleoanthropologist Misia Landau once wrote, stories of human evolution “far exceed what can be inferred from the study of fossils alone,” so fossils are placed “into preexisting narrative structures.”3 And the overarching narrative structure is materialistic philosophy — the view that matter and physical forces are the only realities and God is an illusion.

Science educators tell materialistic stories about how we are accidental by-products of unguided evolution, and the stories are illustrated with iconic drawings of apes morphing into humans. But the stories come first; fossils such as Homo naledi are plugged in later.

References:

(1) Ian Sample, “New haul of Homo naledi bones sheds surprising light on human evolution,” The Guardian (May 9, 2017).

(2) Niles Eldredge and Ian Tattersall, The Myths of Human Evolution (New York: Columbia University Press, 1982), 126–127.

(3) Misia Landau, Narratives of Human Evolution (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1991), pp. ix-x, 148.

The Watchtower Society's commentary on freedom

FREEDOM:

Since Jehovah God is the Almighty, the Sovereign Ruler of the universe, and the Creator of all things, he alone has absolute, unlimited freedom. (Ge 17:1; Jer 10:7, 10; Da 4:34, 35; Re 4:11) All others must move and act within the limitations of ability given them and subject themselves to his universal laws. (Isa 45:9; Ro 9:20, 21) For example, consider gravity, and the laws governing chemical reactions, influence of the sun, and growth; the moral laws; the rights and actions of others that influence one’s freedom. The freedom of all of God’s creatures is therefore a relative freedom.

There is a distinction between limited freedom and bondage. Freedom within God-given limitations brings happiness; bondage to creatures, to imperfection, to weaknesses, or to wrong ideologies brings oppression and unhappiness. Freedom is also to be differentiated from self-determination, that is, ignoring God’s laws and determining for oneself what is right and what is wrong. Such leads to encroachments on the rights of others and causes trouble, as can be seen from the effects of the independent, self-willed spirit introduced to Adam and Eve by the Serpent in Eden. (Ge 3:4, 6, 11-19) True freedom is bounded by law, God’s law, which allows full expression of the individual in a proper, upbuilding, and beneficial way, and which recognizes the rights of others, contributing to happiness for all.—Ps 144:15; Lu 11:28; Jas 1:25.

The God of Freedom. Jehovah is the God of freedom. He freed the nation of Israel from bondage in Egypt. He told them that as long as they obeyed his commandments they would have freedom from want. (De 15:4, 5) David spoke of “freedom from care” within the dwelling towers of Jerusalem. (Ps 122:6, 7) However, the Law provided that in case a man became poor he could sell himself into slavery so as to provide the necessities for himself and his family. But freedom was granted by the Law to this Hebrew in the seventh year of his servitude. (Ex 21:2) In the Jubilee (occurring every 50th year), liberty was proclaimed in the land to all its inhabitants. Every Hebrew slave was freed, and each man was returned to his land inheritance.—Le 25:10-19.

The Freedom That Comes Through Christ. The apostle Paul spoke of the need of humankind to be set free from “enslavement to corruption.” (Ro 8:21) Jesus Christ told Jews who had believed in him: “If you remain in my word, you are really my disciples, and you will know the truth, and the truth will set you free.” To those who thought they had freedom just because they were Abraham’s fleshly descendants, he pointed out that they were slaves of sin, and he said: “Therefore if the Son sets you free, you will be actually free.”—Joh 8:31-36; compare Ro 6:18, 22.

The Christian Greek Scriptures speak of the followers of Christ as being free. Paul showed that they were “children, not of a servant girl, but of the free woman” (Ga 4:31), whom he refers to as being “the Jerusalem above.” (Ga 4:26) He then exhorts: “For such freedom [or, “With her freedom,” ftn] Christ set us free. Therefore stand fast, and do not let yourselves be confined again in a yoke of slavery.” (Ga 5:1) At that time certain men falsely claiming to be Christian had associated themselves with the Galatian congregations. They were making an effort to induce the Galatian Christians to give up their freedom in Christ by trying to gain righteousness by works of the Law, instead of by faith in Christ. Paul warned that they would thereby fall away from Christ’s undeserved kindness.—Ga 5:2-6; 6:12, 13.

The freedom that the early Christians enjoyed from bondage to sin and death and from fear (“For God gave us not a spirit of cowardice, but that of power and of love and of soundness of mind”) was exemplified in the outspokenness and freeness of speech of the apostles in proclaiming the good news. (2Ti 1:7; Ac 4:13; Php 1:18-20) They recognized this freeness of speech about the Christ to be a valuable possession, one that must be developed, guarded, and maintained in order to receive God’s approval. It was also a suitable subject of prayer.—1Ti 3:13; Heb 3:6; Eph 6:18-20.

Proper Use of Christian Freedom. The inspired Christian writers, appreciating God’s purpose in extending undeserved kindness through Christ (“You were, of course, called for freedom, brothers”), repeatedly counseled Christians to guard their freedom and not to take license or wrongful advantage of that freedom as an opportunity to indulge in works of the flesh (Ga 5:13) or as a blind for badness. (1Pe 2:16) James spoke of ‘peering into the perfect law that belongs to freedom’ and pointed out that the one who was not a forgetful hearer, but persisted as a doer, would be happy.—Jas 1:25.

The apostle Paul enjoyed the freedom he had gained through Christ but refrained from using his freedom to please himself or from exercising it to the point of hurting others. In his letter to the congregation at Corinth, he showed that he would not injure another person’s conscience by doing something that he had the Scriptural freedom to do but that might be questioned by another with less knowledge, whose conscience might be offended by Paul’s acts. He cites as an example the eating of meat offered before an idol prior to being put in the market to be sold. Eating such meat might cause one with a weak conscience to criticize Paul’s proper freedom of action and thereby to act as a judge of Paul, which would be wrong. Therefore, Paul said: “Why should it be that my freedom is judged by another person’s conscience? If I am partaking with thanks, why am I to be spoken of abusively over that for which I give thanks?” Nonetheless, the apostle was determined to exercise his freedom in an upbuilding, not a detrimental, way.—1Co 10:23-33.

The Christian’s Fight and Mankind’s Hope. Paul shows that there is a danger to the Christian’s freedom in that, whereas “the law of that spirit which gives life in union with Christ Jesus has set you free from the law of sin and of death” (Ro 8:1, 2), the law of sin and of death working in the Christian’s body fights to bring one into bondage again. Therefore the Christian must set his mind on the things of the spirit in order to win.—Ro 7:21-25; 8:5-8.

After outlining the Christian conflict, Paul goes on to speak of the joint heirs with Christ as “sons of God.” Then he refers to others of mankind as “the creation” and presents the marvelous purpose of God “that the creation itself also will be set free from enslavement to corruption and have the glorious freedom of the children of God.”—Ro 8:12-21.

Figurative Use. When Job, in his suffering, wished to find release in death, he likened death to a freedom for those afflicted. He evidently alludes to the hard lives of slaves, saying: “[In death] the slave is set free from his master.”—Job 3:19; compare verses 21 and 22.

Since Jehovah God is the Almighty, the Sovereign Ruler of the universe, and the Creator of all things, he alone has absolute, unlimited freedom. (Ge 17:1; Jer 10:7, 10; Da 4:34, 35; Re 4:11) All others must move and act within the limitations of ability given them and subject themselves to his universal laws. (Isa 45:9; Ro 9:20, 21) For example, consider gravity, and the laws governing chemical reactions, influence of the sun, and growth; the moral laws; the rights and actions of others that influence one’s freedom. The freedom of all of God’s creatures is therefore a relative freedom.

There is a distinction between limited freedom and bondage. Freedom within God-given limitations brings happiness; bondage to creatures, to imperfection, to weaknesses, or to wrong ideologies brings oppression and unhappiness. Freedom is also to be differentiated from self-determination, that is, ignoring God’s laws and determining for oneself what is right and what is wrong. Such leads to encroachments on the rights of others and causes trouble, as can be seen from the effects of the independent, self-willed spirit introduced to Adam and Eve by the Serpent in Eden. (Ge 3:4, 6, 11-19) True freedom is bounded by law, God’s law, which allows full expression of the individual in a proper, upbuilding, and beneficial way, and which recognizes the rights of others, contributing to happiness for all.—Ps 144:15; Lu 11:28; Jas 1:25.

The God of Freedom. Jehovah is the God of freedom. He freed the nation of Israel from bondage in Egypt. He told them that as long as they obeyed his commandments they would have freedom from want. (De 15:4, 5) David spoke of “freedom from care” within the dwelling towers of Jerusalem. (Ps 122:6, 7) However, the Law provided that in case a man became poor he could sell himself into slavery so as to provide the necessities for himself and his family. But freedom was granted by the Law to this Hebrew in the seventh year of his servitude. (Ex 21:2) In the Jubilee (occurring every 50th year), liberty was proclaimed in the land to all its inhabitants. Every Hebrew slave was freed, and each man was returned to his land inheritance.—Le 25:10-19.

The Freedom That Comes Through Christ. The apostle Paul spoke of the need of humankind to be set free from “enslavement to corruption.” (Ro 8:21) Jesus Christ told Jews who had believed in him: “If you remain in my word, you are really my disciples, and you will know the truth, and the truth will set you free.” To those who thought they had freedom just because they were Abraham’s fleshly descendants, he pointed out that they were slaves of sin, and he said: “Therefore if the Son sets you free, you will be actually free.”—Joh 8:31-36; compare Ro 6:18, 22.

The Christian Greek Scriptures speak of the followers of Christ as being free. Paul showed that they were “children, not of a servant girl, but of the free woman” (Ga 4:31), whom he refers to as being “the Jerusalem above.” (Ga 4:26) He then exhorts: “For such freedom [or, “With her freedom,” ftn] Christ set us free. Therefore stand fast, and do not let yourselves be confined again in a yoke of slavery.” (Ga 5:1) At that time certain men falsely claiming to be Christian had associated themselves with the Galatian congregations. They were making an effort to induce the Galatian Christians to give up their freedom in Christ by trying to gain righteousness by works of the Law, instead of by faith in Christ. Paul warned that they would thereby fall away from Christ’s undeserved kindness.—Ga 5:2-6; 6:12, 13.

The freedom that the early Christians enjoyed from bondage to sin and death and from fear (“For God gave us not a spirit of cowardice, but that of power and of love and of soundness of mind”) was exemplified in the outspokenness and freeness of speech of the apostles in proclaiming the good news. (2Ti 1:7; Ac 4:13; Php 1:18-20) They recognized this freeness of speech about the Christ to be a valuable possession, one that must be developed, guarded, and maintained in order to receive God’s approval. It was also a suitable subject of prayer.—1Ti 3:13; Heb 3:6; Eph 6:18-20.

Proper Use of Christian Freedom. The inspired Christian writers, appreciating God’s purpose in extending undeserved kindness through Christ (“You were, of course, called for freedom, brothers”), repeatedly counseled Christians to guard their freedom and not to take license or wrongful advantage of that freedom as an opportunity to indulge in works of the flesh (Ga 5:13) or as a blind for badness. (1Pe 2:16) James spoke of ‘peering into the perfect law that belongs to freedom’ and pointed out that the one who was not a forgetful hearer, but persisted as a doer, would be happy.—Jas 1:25.

The apostle Paul enjoyed the freedom he had gained through Christ but refrained from using his freedom to please himself or from exercising it to the point of hurting others. In his letter to the congregation at Corinth, he showed that he would not injure another person’s conscience by doing something that he had the Scriptural freedom to do but that might be questioned by another with less knowledge, whose conscience might be offended by Paul’s acts. He cites as an example the eating of meat offered before an idol prior to being put in the market to be sold. Eating such meat might cause one with a weak conscience to criticize Paul’s proper freedom of action and thereby to act as a judge of Paul, which would be wrong. Therefore, Paul said: “Why should it be that my freedom is judged by another person’s conscience? If I am partaking with thanks, why am I to be spoken of abusively over that for which I give thanks?” Nonetheless, the apostle was determined to exercise his freedom in an upbuilding, not a detrimental, way.—1Co 10:23-33.

The Christian’s Fight and Mankind’s Hope. Paul shows that there is a danger to the Christian’s freedom in that, whereas “the law of that spirit which gives life in union with Christ Jesus has set you free from the law of sin and of death” (Ro 8:1, 2), the law of sin and of death working in the Christian’s body fights to bring one into bondage again. Therefore the Christian must set his mind on the things of the spirit in order to win.—Ro 7:21-25; 8:5-8.

After outlining the Christian conflict, Paul goes on to speak of the joint heirs with Christ as “sons of God.” Then he refers to others of mankind as “the creation” and presents the marvelous purpose of God “that the creation itself also will be set free from enslavement to corruption and have the glorious freedom of the children of God.”—Ro 8:12-21.

Figurative Use. When Job, in his suffering, wished to find release in death, he likened death to a freedom for those afflicted. He evidently alludes to the hard lives of slaves, saying: “[In death] the slave is set free from his master.”—Job 3:19; compare verses 21 and 22.

Wednesday, 17 May 2017

On the Cosmocrats:The Watchtower Society's commentary.

DEMON

An invisible, wicked, spirit creature having superhuman powers. The common Greek word for demon (daiʹmon) occurs only once in the Christian Greek Scriptures, in Matthew 8:31; elsewhere the word dai·moʹni·on appears. Pneuʹma, the Greek word for “spirit,” at times is applied to wicked spirits, or demons. (Mt 8:16) It also occurs qualified by terms such as “wicked,” “unclean,” “speechless,” and “deaf.”—Lu 7:21; Mt 10:1; Mr 9:17, 25; see SPIRIT (Spirit Persons).

The demons as such were not created by God. The first to make himself one was Satan the Devil (see SATAN), who became the ruler of other angelic sons of God who also made themselves demons. (Mt 12:24, 26) In Noah’s day disobedient angels materialized, married women, fathered a hybrid generation known as Nephilim (see NEPHILIM), and then dematerialized when the Flood came. (Ge 6:1-4) However, upon returning to the spirit realm, they did not regain their lofty original position, for Jude 6 says: “The angels that did not keep their original position but forsook their own proper dwelling place he has reserved with eternal bonds under dense darkness for the judgment of the great day.” (1Pe 3:19, 20) So it is in this condition of dense spiritual darkness that they must now confine their operations. (2Pe 2:4) Though evidently restrained from materializing, they still have great power and influence over the minds and lives of men, even having the ability to enter into and possess humans and animals, and the facts show that they also use inanimate things such as houses, fetishes, and charms.—Mt 12:43-45; Lu 8:27-33; see DEMON POSSESSION.