Origin-of-Life Researcher Admits, It’s “A Long, Long Way to LUCA”

Evolution News | @DiscoveryCSC

As David Klinghoffer noted briefly here already, a recent paper in Nature Reviews Chemistry, “Studies on the origin of life — the end of the beginning,” opens with a striking admission. In the article, British biochemist John Sutherland concedes the lack of progress in explaining a naturalistic origin of life. Let’s look at this in some more detail. Sutherland writes:

Understanding how life on Earth might have originated is the major goal of origins of life chemistry. To proceed from simple feedstock molecules and energy sources to a living system requires extensive synthesis and coordinated assembly to occur over numerous steps, which are governed only by environmental factors and inherent chemical reactivity. Demonstrating such a process in the laboratory would show how life can start from the inanimate. If the starting materials were irrefutably primordial and the end result happened to bear an uncanny resemblance to extant biology — for what turned out to be purely chemical reasons, albeit elegantly subtle ones — then it could be a recapitulation of the way that natural life originated. We are not yet close to achieving this end, but recent results suggest that we may have nearly finished the first phase: the beginning. [Emphasis added.]

(John D. Sutherland, “Studies on the origin of life — the end of the beginning,” Nature Reviews Chemistry, Vol. 1:12 (2017))

Here, Sutherland admits, as others have done, that scientists are nowhere near figuring out how life arose naturally. Later on in the paper he elaborates on just how far away they really are. More on this in a moment, but let’s quickly examine his claim that scientists are “nearly finished” explaining “the first phase” of the origin of life.

Most theorists think that the origin of life will ultimately be explained as a series of steps, including:

The creation of monomers via prebiotic synthesis

The formation of polymers from those monomers

The formation of a self-replicating molecule

The formation of cells to encapsulate those self-replicating molecules

Of course, there are many other steps along the way, but these are the main ones involved. The first two are thought to have involved pure chemistry — what one might call “necessity,” or things bound to happen given the deterministic laws of nature.

The last two steps are considered to be more a matter of contingency. That is, they things that did not have to happen and may have simply occurred due to lucky happenstance. This is because, as we’ll see, forming complex polymers (like RNA) — which scientists are still nowhere near explaining — provides no guarantee that you’ll generate the right sequences of nucleotides in those RNAs to yield a self-replicating molecule.

So what Sutherland claims we’re close to explaining is merely the first step: forming simple organic monomers via chemical reactions that were bound to happen under chemical processes on the early earth. Or were they?

We’ve reviewed Sutherland’s work here at Evolution News in the past. He and his team have focused on how to explain the origin of nucleotides under natural chemical conditions. His research produced some nucleotides. Whether it mimicked plausible conditions that might have existed naturally on the early earth is an entirely different question.

For example, in 2009 he co-authored a paper in Nature purporting to produce activated pyrimidine ribonucleotides under “prebiotically plausible conditions.” An evaluation of his paper showed the conditions weren’t so prebiotically plausible after all. After the New York Times praised Sutherland’s paper, Discovery Institute’s Stephen Meyer wrote a response noting that it “fail[s] to address the fundamental issue that has generated the longstanding impasse in the field: the problem of the origin of biological information.” Later, Meyer observed that “not only does this study not address the problem of getting nucleotide bases to arrange themselves into functionally specified sequences, but the extent to which it does succeed in producing biologically relevant chemical constituents of RNA actually illustrates the indispensable role of intelligence in generating such chemistry.”

In a subsequent post, Casey Luskin asked various pro-ID chemists to review Sutherland’s research. They concluded that Sutherland’s reactions required substantial intelligent intervention and would certainly never occur under blind and unguided natural conditions:

“The starting materials are ‘plausibly’ obtainable by abiotic means, but need to be kept isolated from one another until the right step, as Sutherland admits. One of the starting materials is a single mirror image for which there is no plausible way to get it that way abiotically. Then Sutherland ran these reactions as any organic chemist would, with pure materials under carefully controlled conditions. In general, he purified the desired products after each step, and adjusted the conditions (pH, temperature, etc.) to maximum advantage along the way. Not at all what one would expect from a lagoon of organic soup. He recognized that making of a lot of biologically problematic side products was inevitable, but found that UV light applied at the right time and for the right duration could destroy much (?) of the junk without too much damage to the desired material. Meaning, of course, that without great care little of the desired chemistry would plausibly occur. But it is more than enough for true believers in OOL to rejoice over, and, predictably, to way overstate in the press.”

“They used pH manipulation, phosphate buffers, and irradiation all at the correct times and amounts to achieve their goal, which was to produce ‘activated pyrimidine ribonucleotides.’ Indeed, they could have shortened their title by chopping off the last four words and sent the paper to the Journal of Organic Synthesis and had a good chance of getting it accepted as a novel synthetic route with full credit to themselves for their clever manipulations. Certainly the fingerprints of several intelligent chemists are all over this pathway if not their rather ham-fisted signatures.”

Senior origin-of-life researcher Robert Shapiro chimed in and criticized Sutherland’s work, saying: “Although as an exercise in chemistry this represents some very elegant work, this has nothing to do with the origin of life on Earth whatsoever….The chances that blind, undirected, inanimate chemistry would go out of its way in multiple steps and use of reagents in just the right sequence to form RNA is highly unlikely.” Meanwhile, a peer-reviewed paper in Accounts of Chemical Research took Sutherland and his team to task for using unrealistic, implausible pathways to generate the nucleotides:

Notwithstanding is merits, Sutherland’s approach is discounted by many in the bio-origins community. It is perhaps easy to see why. In their attempt to avoid the “water problem” for the glycosidic bond, Sutherland et al. drive themselves back into the “asphalt problem.” Their alternative synthesis requires human addition (at the right times) of high concentrations of two carbohydrates, glycolaldehyde and glyceraldehyde. These carbohydrates are too reactive to accumulate prebiotically, even with borate.

Reviewing Sutherland’s proposed route, Shapiro noted that it resembled a golfer, having played an 18 hole course, claiming that he had shown that the golf ball could have, through some combination of wind, rain, heating, cooling, dehydration, and ultraviolet irradiation played itself around the course without the golfer’s presence.

Perhaps recognizing this, Sutherland and his co-workers wrote, “Although the issue of temporally separated supplies of glycolaldehyde and glyceraldehyde remains a problem, a number of situations could have arisen that would result in the conditions of heating and progressive dehydration followed by cooling, rehydration and ultraviolet irradiation. Comparative assessment of these models is beyond the scope of this work.”

In Shapiro’s view, the need for “temporally separated supplies of glycolaldehyde and glyceraldehyde” is more than “a problem…beyond the scope” of this work. It is a fatal flaw.

(Stephen Benner, Hyo-Joong Kim, and Matthew A. Carrigan, “Asphalt, Water, and the Prebiotic Synthesis of Ribose, Ribonucleosides, and RNA,” Accounts of Chemical Research, Vol. 45:2025-2034 (2012))

Then, in 2015 Sutherland co-published a paper in Nature Chemistry purporting to create the precursors of pyrimidine nucleotides in a manner that also produced precursors to amino acids (which build proteins) and lipids. This led the journal Science to excitedly proclaim, “Researchers may have solved origin-of-life conundrum.” But the research had the same problems as before. Again Casey Luskin asked an ID-friendly biochemist to weigh in:

I read the article by Patel et al (2015) that appeared in Nature Chemistry. While it is full of fascinating chemistry, given all of the manipulation of pH, precursor mixes, temperature, metal co-ions, etc., it is beyond the pale to pretend that anything in this paper represents undirected pre-biotic chemistry. The only way this paper represents a solution to origin-of-life issues is for Patel et al. to be time travelers who manipulated the pre-biotic environment to produce the building blocks of life….To claim that the whole suite of “precursors of ribonucleotides, amino acids and lipids can all be derived by the reductive homologation of hydrogen cyanide and some of its derivatives” rests on how one defines what are plausible early Earth conditions. By admitting that the products vary depending upon reaction conditions and metallic co-ions, the idea of a one-pot synthesis is not viable in this scenario. They also stretch the concept of “plausibility” to a new extreme. While it is easy to imagine a series of pools of the appropriate conditions and with the appropriate precursor compounds all feeding into a single pool, it would be wrong to conclude that what we can imagine is science.

In short, from the prebiotic perspective, Sutherland’s research up to now has been implausible. This brings us to his new article in Nature Reviews Chemistry. He candidly discusses the gap between prebiotic chemistry, which happens without enzyme catalysts, and biological chemistry, which uses all kinds of biomolecules to regulate biochemistry:

Biology almost always relies on chemistry that does not proceed efficiently in the absence of catalysis, because this allows chemistry to be regulated by dialling various catalysts up or down. However, most prebiotic chemistry must proceed of its own accord, and this surely suggests that it must generally be different from the underlying chemistry used in biology….Nevertheless, despite the inevitable widespread differences between their individual reactions, prebiotic reaction networks ultimately have to transition into biochemical networks; hence, there must be some similarities between the two, if only at the level that practitioners of synthesis would view as strategic.

Sutherland thus views similarities between biological chemistry and blind, nonbiological (and possibly prebiotic) chemistry as hinting at how biological chemistry arose. As in his 2015 paper, in the 2017 review he outlines a scenario for generating the precursors of nucleotides, amino acids, and lipids. He seems aware that this scenario, requiring a long series of steps and the addition of chemical species at just the right stages, might not be convincing. He sums up his explanation as follows:

Remarkably, when these few reduction reactions are combined with several addition reactions and a dry-state phosphorylation (conditions for which were discovered nearly half a century ago but are still being rediscovered), a reaction network leading from hydrogen cyanide 2 (and a few of its derivatives) to the pyrimidine nucleotides, and to precursors to a dozen amino acids and glycerol phosphate lipids, can be defined. The reactions are all high yielding and lead to little else besides biomolecules or their precursors. It is not definitive proof that the building blocks of biology arose in this way, but it is compelling and indicates that the requirements for these reactions to take place should be used to constrain geochemical scenarios on the early Earth. A requirement for ultraviolet irradiation to generate hydrated electrons would rule out deep sea environments. This, along with strong bioenergetic and structural arguments, suggests that the idea that life originated at vents should, like the vents themselves, remain “In the deep bosom of the ocean buried.” The chemistry places certain demands on the environment of the early Earth: for example, the high concentrations of certain species through evaporation of solutions. Supporters welcome these demands as constraints that help refine primitive Earth scenarios. Detractors view them as unacceptable but must surely then demonstrate that other scenarios can be equally productive.

Aside from the fact that Sutherland’s model refutes the ever-popular “hydrothermal vent” hypothesis for the origin of life, don’t miss the last sentence where he commits the “burden of proof” logical fallacy. This basically says that if you view his scenario as “unacceptable” then you can’t dismiss it unless you can produce a scenario that’s better or “equally productive.” This is obviously fallacious: the merits of his hypothesis do not fall or rise on the ability of a given critic to provide a more “productive” explanation. After all, what if the entire project — the attempt to produce biomolecules in the absence of living organisms under natural earthlike conditions — is impossible? If that’s the case, then all explanations of prebiotic synthesis are ultimately doomed to fail, including our “best” attempts. Perhaps the fact that he ends on this note hints that he knows his case isn’t really all that strong.

Indeed, he reassures skeptics, saying: “The resemblance to modern biochemistry might not be obvious to the non-chemist at first, but it is to those with chemical acuity.” That’s another logical fallacy for you — the “genetic fallacy,” which attacks people personally, in this instance for being “non-chemists,” rather than their arguments.

In any case, the scenario of prebiotic synthesis he outlines once again suffers from the problems that his earlier work did. As Robert Shapiro put it, it is “highly unlikely” that “blind, undirected, inanimate chemistry would go out of its way in multiple steps and use of reagents in just the right sequence to form RNA.”

Sutherland’s reference in his paper’s title to “the end of the beginning” means he thinks we’re near the end of explaining how simple biological monomers might have arisen on the early earth in the absence of living organisms. That is step (1) (“the beginning”) in the list above. However, if Shapiro and other critics are correct, then Sutherland is probably still pretty far from the end of the beginning. And even if Sutherland were correct, he admits just how far a full-fledged explanation for step (1) is from explaining the origin of life:

[T]he prebiotic synthesis of building blocks — to which we have devoted so much of our time — only corresponds to a small increase in the complexity of the system and to no increase in its aliveness (a humbling thought).

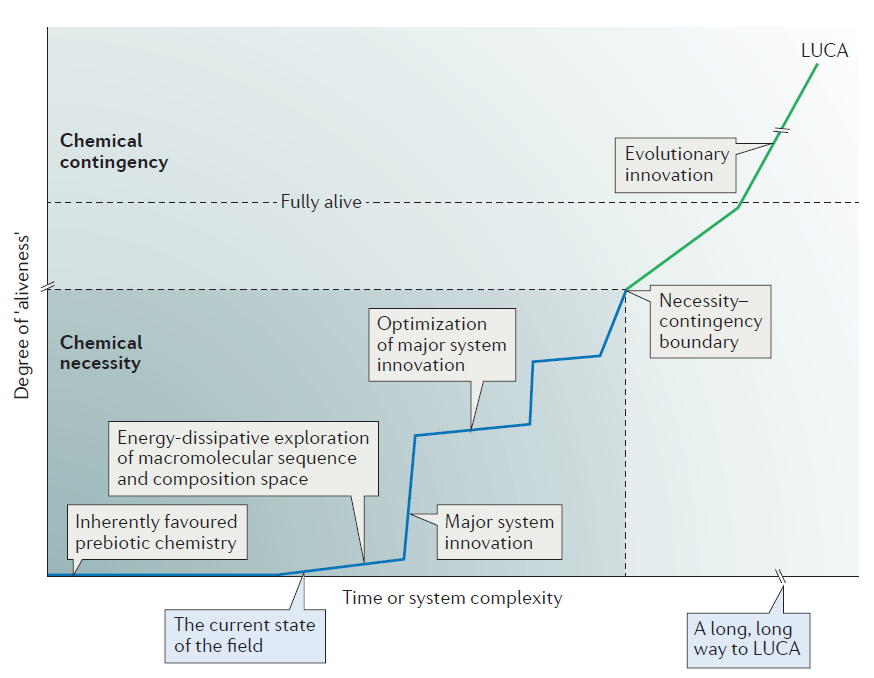

Figure 3 in his review paper illustrates the distance that origin-of-life theorists must traverse to explain the chemical origin of life and the origin of LUCA — the last universal common ancestor of all living organisms:

Note the box indicating “The current state of the field.” It’s pretty far down the road of things needing to be explained. Thus, even in Sutherland’s overly optimistic view, they haven’t begun to explain how these prebiotic monomers could combine to form larger polymers such as RNA and then begin to explore sequence-space. This is, in his own words, “A long, long way to LUCA.”

But what if somehow Sutherland et al. could solve all of these problems and could thus produce RNAs via unguided chemical reactions? Benner et al. 2012 (quoted above) point out why this would likely be a dead end for origin-of-life research:

[C]urrent experiments suggest that RNA molecules that catalyze the degradation of RNA are more likely to emerge from a library of random RNA molecules than RNA molecules that catalyze the template-directed synthesis of RNA, especially given cofactors (e.g., Mg2+). This could, of course, be a serious (and possibly fatal) flaw to the RNA-first hypothesis for bio-origins.

That’s a major issue. Even if you can produce random RNA molecules, you’re much more likely to produce RNAs that degrade other RNAs than those that can replicate new ones. This goes back to Stephen Meyer’s original criticism of Sutherland’s work: without intelligence to generate information and properly order nucleotides, you are exceedingly unlikely to get the needed sequences to produce a living, self-replicating organism. Or to put it in Sutherland’s language, only input from an intelligence can allow you to cross the necessity-contingency boundary and produce something that approaches “aliveness,” much less something that is “fully alive.”

In fact, Sutherland seems aware that this is a problem for naturalistic models. As he writes:

However, this synthesis is necessary to put the system on the right path, and knowing the steps that have been taken can give some hints as to the nature of the steps that follow, at least up to a point: the necessity-contingency boundary when the synthesis of macromolecules from multiple monomers reaches the stage in which only a fraction of all possible sequence variants can be sampled owing to the number of possible permutations exceeding the number of molecules.

In other words, even if we explain how to generate lots of RNAs, how do we get the very unlikely sequences that yield living organisms? The answer is staring him and other origin-of-life theorists in the face, but most aren’t willing to see it: In all of our experience with the origin of complex and specified information, only intelligent design can generate the sequence-specific digital information necessary to cross the necessity-contingency boundary and generate a self-replicating living organism.